November 18th, 2008 by Dr. Val Jones in Opinion, Quackery Exposed

20 Comments »

The internet, in democratizing knowledge, has led a lot of people to believe that it is also possible to democratize expertise.

– Commenter at Science Based Medicine

Regular readers of this blog know how passionate I am about protecting the public from misleading health information. I have witnessed first-hand many well-meaning attempts to “empower consumers” with Web 2.0 tools. Unfortunately, they were designed without a clear understanding of the scientific method, basic statistics, or in some cases, common sense.

Let me first say that I desperately want my patients to be knowledgeable about their disease or condition. The quality of their self-care depends on that, and I regularly point each of my patients to trusted sources of health information so that they can be fully informed about all aspects of their health. Informed decisions are founded upon good information. But when the foundation is corrupt – consumer empowerment collapses like a house of cards.

In a recent lecture on Health 2.0, it was suggested that websites that enable patients to “conduct their own clinical trials” are the bold new frontier of research. This assertion betrays a lack of understanding of basic scientific principles. In healthcare we often say, “the plural of anecdote is not data” and I would translate that to “research minus science equals gossip.” Let me give you some examples of Health 2.0 gone wild:

1. A rating tool was created to “empower” patients to score their medications (and user-generated treatment options) based on their perceived efficacy for their disease/condition. The treatments with the highest average scores would surely reflect the best option for a given disease/condition, right? Wrong. Every single pain syndrome (from headache to low back pain) suggested a narcotic was the most popular (and therefore “best”) treatment. If patients followed this system for determining their treatment options, we’d be swatting flies with cannon balls – not to mention being at risk for drug dependency and even abuse. Treatments must be carefully customized to the individual – genetic differences, allergy profiles, comorbid conditions, and psychosocial and financial considerations all play an important role in choosing the best treatment. Removing those subtleties from the decision-making process is a backwards step for healthcare.

2. An online tracker tool was created without the input of a clinician. The tool purported to “empower women” to manage menopause more effectively online. What on earth would a woman want to do to manage her menopause online, you might ask? Well apparently these young software developers strongly believed that a “hot flash tracker” would be just what women were looking for. The tool provided a graphical representation of the frequency and duration of hot flashes, so that the user could present this to her doctor. One small problem: hot flash management is a binary decision. Hot flashes either are so personally bothersome that a woman would decide to receive hormone therapy to reduce their effects, or the hot flashes are not bothersome enough to warrant treatment. It doesn’t matter how frequently they occur or how long they last. Another ill-conceived Health 2.0 tool.

When it comes to interpreting data, Barker Bausell does an admirable job of reviewing the most common reasons why people are misled to believe that there is a cause and effect relationship between a given intervention and outcome. In fact, the deck is stacked in favor of a perceived effect in any trial, so it’s important to be aware of these potential biases when interpreting results. Health 2.0 enthusiasts would do well to consider the following factors that create the potential for “false positives”in any clinical trial:

1. Natural History: most medical conditions have fluctuating symptoms and many improve on their own over time. Therefore, for many conditions, one would expect improvement during the course of study, regardless of treatment.

2. Regression to the Mean: people are more likely to join a research study when their illness/problem is at its worst during its natural history. Therefore, it is more likely that the symptoms will improve during the study than if they joined at times when symptoms were not as troublesome. Therefore, in any given study – there is a tendency for participants in particular to improve after joining.

3. The Hawthorne Effect: people behave differently and experience treatment differently when they’re being studied. So for example, if people know they’re being observed regarding their work productivity, they’re likely to work harder during the research study. The enhanced results therefore, do not reflect typical behavior.

4. Limitations of Memory: studies have shown that people ascribe greater improvement of symptoms in retrospect. Research that relies on patient recall is in danger of increased false positive rates.

5. Experimenter Bias: it is difficult for researchers to treat all study subjects in an identical manner if they know which patient is receiving an experimental treatment versus a placebo. Their gestures and the way that they question the subjects may set up expectations of benefit. Also, scientists are eager to demonstrate positive results for publication purposes.

6. Experimental Attrition: people generally join research studies because they expect that they may benefit from the treatment they receive. If they suspect that they are in the placebo group, they are more likely to drop out of the study. This can influence the study results so that the sicker patients who are not finding benefit with the placebo drop out, leaving the milder cases to try to tease out their response to the intervention.

7. The Placebo Effect: I saved the most important artifact for last. The natural tendency for study subjects is to perceive that a treatment is effective. Previous research has shown that about 33% of study subjects will report that the placebo has a positive therapeutic effect of some sort.

In my opinion, the often-missing ingredient in Health 2.0 is the medical expert. Without our critical review and educated guidance, there is a greater risk of making irrelevant tools or perhaps even doing more harm than good. Let’s all work closely together to harness the power of the Internet for our common good. While research minus science = gossip, science minus consumers = inaction.

November 17th, 2008 by Dr. Val Jones in Announcements

4 Comments »

I was a panelist at Edelman’s CHPA New Media Summit today in New Brunswick, NJ. Matthew Holt (of the Healthcare Blog and Health 2.0) was the keynote speaker, and I participated on a panel discussion with Dr. Roy Poses. It was exciting to meet Roy in person for the first time, as I’ve been following his policy blog for some time.

Matthew presented a very rosy picture of Health 2.0 (consumer-driven healthcare), more or less suggesting that it could provide a large part of the solution to our current healthcare crisis. I countered with a more cautious view, explaining that expert engagement would be critical to Health 2.0’s success.

Matthew argued that sites like Patients Like Me were enabling patients “to do their own clinical trials online,” and that this was opening a whole new avenue for research. Dr. Poses and I were fairly concerned about this suggestion, primarily because we understand how easy it is to draw false conclusions from data, especially when the data are not collected in a systematic fashion.

I explained to the audience that association does not prove causation (E.g. Do matches cause lung cancer? No, though it’s true that people who smoke are more likely to carry matches). I also described a case in which a Health 2.0 principle went terribly awry: a group of consumers were asked to rate their medications for efficacy by disease/condition. This was supposed to leverage the “wisdom of the crowds” to determine which medicines worked best (by popular vote). Of course, the result was that every pain syndrome (low back pain, headaches, fibromyalgia, etc.) resulted in a narcotic pain medicine as the highest ranked treatment option. Do you really need Oxycontin for that tension headache of yours? Obviously, narcotics are popular among users – but are a last resort for pain management in the real world. The “wisdom of crowds” rarely works in healthcare.

Matthew agreed to disagree with me on a number of issues – but we certainly found common ground on the primary care crisis. He and I both believe that a shortage of primary care physicians is going to result in a catastrophic shortage of care for Baby Boomers in the next decade. Dr. Poses added that primary care physicians make the same salary as school teachers in his home state of Rhode Island.

I think we have to agree with KevinMD – the way forward is not going to be pretty.

November 16th, 2008 by Dr. Val Jones in Announcements

No Comments »

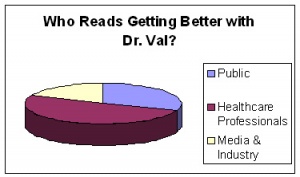

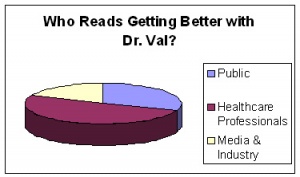

I asked my blog readers to tell me who they were (poll results: n=145) and this is the breakdown:

I think that’s pretty interesting data – it seems that my blog appeals to doctors, nurses, allied health professionals, the general public and media/industry folks to boot. I was a little sad to see that pets were not as large a contingent as I had expected. I’ll need to work harder to reach that demographic, I suppose.

Gratuitous cat photo:

November 15th, 2008 by Dr. Val Jones in Humor

No Comments »

My husband doesn’t like it when I go shopping with his credit card. But I tried to cheer him up about it. I said, “Honey, every purchase is a vote of confidence in your earning power.”

– Joan Horbiak, MPH, RD, at the Dairy Science Forum, November 13, 2008

November 15th, 2008 by Dr. Val Jones in Expert Interviews

1 Comment »

It is estimated that 75% of our healthcare dollars are spent on chronic disease management, and that 80% of chronic diseases could be avoided with diet and lifestyle interventions. This means that the best way to decrease the size of our healthcare budget is to decrease the size of our collective waistlines. And that’s no small task.

It is estimated that 75% of our healthcare dollars are spent on chronic disease management, and that 80% of chronic diseases could be avoided with diet and lifestyle interventions. This means that the best way to decrease the size of our healthcare budget is to decrease the size of our collective waistlines. And that’s no small task.

Going back to basics – healthy eating and regular exercise – is such a simple message. But what is healthy eating exactly? Consumers are fairly exhausted by the complex messages they’ve heard about food and nutrition over the past couple of decades. One minute anti-oxidant foods are a miracle cure for everything from cancer to facial wrinkles, the next, it seems that they actually increase the risk of death. Diet advice ranging from low fat, low carb, to low sugar have all been promoted as the healthiest way to lose weight. But what does the evidence actually show? I decided to interview a series of experts to try to glean what I could about the state of nutrition knowledge. Today’s post is about protein – and I interviewed Nancy Rodriguez, PhD, a “protein scientist” to weigh in on this nutrient.

Dr. Val: We don’t talk about dietary protein needs that much, Nancy. Why is that?

Dr. Rodriguez: In the United States most people do get at least the minimum required amount of protein/day. The RDA (recommended daily allowance) of 0.8g/Kg of body weight is the amount you need to consume to avoid an outright protein deficiency. That’s about 3 ounces of chicken, fish, or meat/day – the size of a deck of cards. But the real benefits of protein include appetite suppression, and thermogenesis. Studies show that if people eat a little bit of protein with each meal, they’re less likely to become hungry between meals or consume as many calories overall. You also end up burning a few calories in the process of digesting protein.

Dr. Val: So what is the appropriate amount of protein intake?

Dr. Rodriguez: I have found that 1.2-1.5g/Kg may be optimal for hunger management. That means we should try to get a little bit of protein with each meal. Weight maintenance and loss is much easier to achieve if you don’t feel hungry all the time. Protein can really help with that.

Dr. Val: Is it possible to eat too much protein? Can it damage the kidneys in excess?

Dr. Rodriguez: I’ve conducted a few studies with participants eating 3g/kg of protein. That’s really hard to do. For example, you have to eat eggs and bacon for breakfast, 2 chicken breasts and veggies for lunch, and a 10oz steak for dinner. This is clearly in excess of what we need, though it’s hard to say if that level of protein is harmful. If someone has kidney disease, then obviously it would be a really bad idea to tax the kidneys with removing so many protein break down products. But people with normal kidney function didn’t seem to have a problem clearing the protein. Protein isn’t stored. When you consume more of it than your body needs, it is simply broken down and removed via the urine.

I personally don’t believe that excess protein causes kidney disease, but it can be a problem for those who have kidney disease. We would have to do some very long term studies of people eating very high protein diets for decades to find out if they end up with a higher risk of kidney disease. We just don’t know yet. But our kidneys have a tremendous reserve capacity to filter the blood. We can easily live with just one kidney – so it’s possible that healthy kidneys can handle high protein diets without injury. One thing that I certainly recommend – if you eat a lot of protein, you should drink a lot of water to help to flush out the break down products.

Dr. Val: Is it true that whey protein may help to reduce high blood pressure?

Dr. Rodriguez: Milk proteins are very interesting in that they contain a broad array of bioactive substances. There is increasing evidence that lactokinins can reduce blood pressure, but we just don’t understand the exact mechanism yet. We do know that people who eat more dairy products (included in the DASH diet plan) can lower their systolic blood pressure by an average of 10 mmHg.

Whey protein is also a natural appetite suppressant, so it can be helpful part of a weight loss strategy. Dairy sources of protein are an important part of a healthy diet.

***

I caught up with Nancy at the Dairy Science Forum on November 13th, 2008 in Washington, DC.

|

|

Nancy Rodriguez

|

Nancy Rodriguez, PhD, RD, CSSD, FACSM, is a professor of Nutritional Sciences in the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources (CANR) at the University of Connecticut, with joint appointments in the Departments of Kinesiology and Allied Health Sciences. She is director of Sports Nutrition in the Department of Sports Medicine in the Division of Athletics.