May 20th, 2009 by SteveSimmonsMD in Primary Care Wednesdays

Tags: Doctor Patient Relationship, Dr. Steve Simmons, Elder care, Health Policy, Healthcare Rationing, Healthcare reform, Medicare

4 Comments »

The impetus for government to control healthcare costs should be obvious to us all and intervention now appears unavoidable. Two issues will soon come to light: the exorbitant costs to fight disease at the end of life, often when the approach of death is barely retarded and the wide disparity in costs between different geographical regions of our country for similarly aged patients. It is estimated that 27% of Medicare’s annual $327 billion budget – one fourth of its operating budget – goes to care for patients in their final year of life while Medicare averages $20,000 more dollars for patients in Manhattan than in some rural areas of our country.

With this in mind, I share a deep concern with many of my colleagues that part of the healthcare reform debate will turn to the rationing of healthcare. This appears a logical progression from the proposed establishment of guidelines and advisory committees currently allowed for in the Health Reform bill already passed. The question as to who should receive possibly futile care is not clear, rather it is fraught with complexity, often relying as much on evidence-based research as it is on assessments made by the medical practitioner in light of the relationship the doctor has with the patient.

At the heart of the rationing issue are two, often warring, sides of medicine: art and science. Medicine began as an art thousands of years ago, and moved more towards science when, in Ancient Greece, Hippocrates taught physicians to observe the results of their treatments and make adjustments. However, art should not be removed from medicine, for this is where the doctor-patient relationship comes to play, serving as a cornerstone of effective and humane medicine. It would be impossible for physicians to uphold the noble traditions of the medical profession, adequately serve society, or preserve the dignity of human life if doctors were to become, purely, scientists. As long as we are treating people, medicine should never become solely a science.

Rationing, however, would be based purely on science, completely devoid of any art and, I believe, serve as a blow against the sanctity of the medical profession. Setting up rationing guidelines as they pertain to the end of life would circumvent patient’s trust in the doctor-patient relationship and risk the very soul of medicine by negating the importance of the doctor-patient relationship. Evidence-based recommendations can and should be set forth pertaining to protocols for offering treatments as the end of life seems near. This would likely reduce some of the high and disparate costs in caring for our elders; however, it is important to consider the input of a doctor aware of the needs and desires of his patient.

I come to this argument both as a physician and from personal experience. Several years ago, my 75 year old father was hospitalized four times over five months. His medical team, led by a kind and experienced surgeon, unburdened by guidelines or anyone else’s recommendations, gave him a chance despite long odds against his survival. Medically speaking, I am still surprised he made it out of the hospital to live a normal life again. During the subsequent five years, he has welcomed three grandchildren into our family; I would challenge anyone to assign a monetary value for that life experience. My professional and personal experience leaves me quite sure that he would have fallen a victim of any rationing guidelines that could ever exist.

In short, as the average life span increases most of us nurture the hope to live longer, cheering as science opens the door to seemingly innumerable advancements. Yet are we, as a society, equipped, whether it be emotionally or fiscally, to handle the decisions that must be made as the end of life draws near? More importantly, should government be allowed to set up strict guidelines without an active debate from physicians and patients? These guidelines could sacrifice what has long been and should still remain most important to healthcare: the doctor-patient relationship.

May 13th, 2009 by AlanDappenMD in Primary Care Wednesdays

Tags: Doctokr Family Medicine, Dr. Alan Dappen, Primary Care, Primary Care Wednesdays, Remote Access Visits, Telemedicine

No Comments »

“OK,” I can hear you say, “Enough about telemedicine. So what if you can prevent two-thirds of office visits by using the phones, or that it’s convenient for the patient and can start them on the road to recovery faster, or that it costs much less money than conducting an office visit, or that malpractice companies have accepted this delivery model.

I can see that you still side with the other non-believers in telemedicine, citing, “Telemedicine is no way to build relationship with patients. Problems abound with telemedicine: It’s too impersonal, patients could easily not be telling you the truth because you lose the “body language and facial expressions,” and it certainly can’t be useful for chronic illness. Maybe it’s good for the simple problems, but this has no place with complex or chronic medical care.”

I do, of course, have some rebuttals for you …

Let’s start with impersonal. In today’s world, we let our friends and family communicate with us constantly through phones and email, and I’ve yet to see how this has destroyed the intimacy of our relationships. So why do Americans anxiously wait up to four days for a doctor’s appointment to get their problem or question resolved and waste at least four hours of a day to get to the office simply to wait for an unpredictable time for a predictable 10-15 minutes of the doctor’s time when so many issues can be resolved remotely by phone? Furthermore, try convincing someone with a urinary tract infection (UTI) or that needs a prescription refill that their long wait, suffering, and run through the primary care funnel were “good for the relationship.” In fact, nothing is more personal that a doctor saying to their patients, “Here is my direct phone number, please call me anytime you need help.” Viewing telemedicine from this perspective determines that the “impersonal” concern is a ruse to protect doctor’s privacy at the expense of their patients.

What about the patient who is not truthful? Does a face-to-face visit make this less likely? In 30 years of work, several patients I know have not always been honest. Many of these people were attractively dressed, well educated and for awhile, fooled me badly. I saw them all face to face too. To this day, I have no idea what to look for when someone is trying to pull the wool over my eyes.

If people are going to hide the truth, they can do it in person just as well as over the phone. When a doctor becomes suspicious about a patient’s truthfulness through a pattern of calls and behaviors, then a scheduled office visit may help. However, forcing office visits based on a blanket rule of thumb of not trusting your patients means there is something fundamentally wrong with the doctor-patient relationship.

Lastly is the idea that chronic disease management isn’t appropriate through phones and email. Really? Let’s say you had diabetes, or hypertension, or high cholesterol, or cancer, or depression, just to name a few. With one of these conditions, you will be in contact with your health professional a lot more than you are now. Not only is your life more complicated, but the doctor wants you to consume 10% of your life waiting to see him in person because it’s good for him. Instead, many of these visits can be conducted easily anytime through phone calls and email.

Here are some examples:

#1. A phone call: “Mr. Doe this is Dr Dappen. I see a calendar reminder that you’re due for labs to check your cholesterol and to make sure the statin drug we put you on is not causing problems. I’ve faxed the order to the lab that is located close to you home, so stop by anytime in the next week and they’ll draw the blood. I should have the results in 24 hours after your visit to the lab, and we can review the report over the phone at that time and decide if we need to make any change.”

#2. An email from a patient: “Dr. Dappen, I’ve been worrying about my blood pressure readings. Over the past 3 weeks, they’ve been running consistently higher. Not sure why and until recently the home readings were doing great. Attached is the spread sheet of readings. Look forward to your input.”

In fact, examples abound of how chronic disease management conducted via phones and email is more efficient, reduces costs, and improves outcomes; I’d invite any Doubting Thomas to visit the American Telemedicine Association for further inquiry. An entire telemedicine industry is gearing up to manage chronic illnesses and most of the time it has nothing to do with patients visiting doctors’ offices.

When all is said and analyzed, the conclusion is really simple as to why the use of telemedicine is not more prevalent: no one wants to pay a doctor the market value for the time it takes to answer a phone and expedite an acute problem or manage a chronic health care problem. No money means no mission. This means no phones, no email. Don’t think about it. See you in the office. Why ruin 2400 years of tradition?

May 6th, 2009 by SteveSimmonsMD in Primary Care Wednesdays

Tags: Dr. Steve Simmons, H1N1, Influenza, Swine Flu, Vaccines

2 Comments »

Swine Flu has brought an awareness of the catastrophic potential inherent in pandemic influenza to the public consciousness and led many to panic. Industry has long played a major role in protecting us against epidemic influenza, providing doctors and patients with vaccinations and medications to help protect and treat the weakest individuals in our society: the young and old. However, pandemic flu frequently kills the healthiest in society; a hallmark of the 1918 Swine Flu Pandemic that left 500,000 dead in the U.S., far more that the average of 36,000 dead in a typical year.

This week, I had a discussion with Bill Enright, President and CEO of Vaxin Inc., about their efforts to create a vaccine for pandemic Flu. Our daughters are kindergarten classmates and over the last two years I have enjoyed the opportunity our friendship has afforded me to learn about the vaccine industry. As “Swine Flu” began to dominate the headlines I asked him to participate in a dialogue with me believing that a discussion between a clinical physician and a vaccine scientist would be interesting and informative for a reader without giving in to hysteria. He was kind enough to give of his own time and a part of the discussion follows:

STEVE: What is Vaxin, Inc.?

BILL:. Vaxin is a vaccine development company focused on needle-free vaccines to protect against influenza (both seasonal and avian influenza) and anthrax. Using technology developed at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, by our scientific founder Dr. De-chu Tang, we have been able to show proof of principle with our platform, intranasal seasonal influenza vaccine, and have just completed enrollment in a Phase I clinical study with an intranasal pre-pandemic influenza vaccine. We are also investigating patch-based vaccines.

STEVE: What is the difference between the vaccine you are developing for Pandemic Influenza and the vaccine given yearly for Epidemic Influenza?

BILL: Epidemic, or seasonal, vaccines are trivalent vaccines composed of three influenza strains (two A and one B) anticipated to be circulating. The CDC and the WHO spend considerable effort in monitoring the circulating strains around the world before making a decision on which strains should be included in that year’s vaccine. However, several changes could occur which result in the vaccine not being a good match for a particular year: mutations could change a strain, new strains could evolve or different strains than anticipated could predominate.

Pandemic vaccines will be made to the circulating influenza virus causing the pandemic. Vaccines made in advance of a pandemic are really “pre-pandemic” vaccines as they are attempting to estimate which influenza strain may make the jump to a pandemic and enable stockpiling and/or vaccination of at-risk individuals with the belief that the vaccine will mitigate symptoms and decrease mortality through cross-strain protection while a true pandemic vaccine is being developed/manufactured.

STEVE: How long does it take to produce an epidemic trivalent vaccine and is it feasible to have the current H1N1 strain or “swine flu,” included in the standard flu shot this fall?

BILL: That is a complex question. Do you include it as a 4th component? Replace one of the other A strains? Provide it as a separate vaccine? Manufacturers are currently trying to assess how much and of which type of vaccine they would be able to provide given a limited egg supply (since vaccine components require incubation in chicken eggs). Chicken populations take a significant amount of time to increase to add egg capacity. Seasonal vaccine antigen doses are typically 15µg and it takes approximately 1 egg for one, 15µg dose. To date it has taken 90µg of antigen to show similar levelsof efficacy for pandemic vaccines. Therefore, whether or not there is a sufficient egg supply and how that may impact the traditional epidemic vaccine is being discussed and calculated as we speak.

The length of time it takes to manufacture the epidemic trivalent vaccine depends a lot on the specific strains and how different the vaccine is from the previous year. For instance, the 09/10 vaccine will contain 2 of the same strains as the 08/09 version, only the B strain is different. The CDC put forward this years policy document on February 25th, identifying which exact strains were to be included in this year’s vaccine. Many manufacturers had already started the production efforts on the seed strains guessing that these would be the strains based on available surveillance of circulating strains. Typically the total process begins in December or January for most manufacturers. Usually the first vaccines are ready to ship to distributors in August or September. In certain years the process can take longer than usual because not all strains of influenza grow well in chicken eggs, including the recent H1N1 virus. New “reverse genetic” techniques are helping to alleviate this problem but the rate of growth and yield of virus continues to be a concern to manufacturers.

STEVE: Do you have any ongoing clinical trials for the H5 pre-pandemic flu?

BILL: Vaxin is currently completing a Phase I clinical trial for an intranasally delivered vaccine against the H5N1 influenza virus. This is the first step in getting a vaccine approved for use by the FDA. Typically Phase I trials involve a small number of otherwise healthy volunteers that agree to be vaccinated to allow us to test and ensure that our vaccine does not cause any serious unwanted safety concerns. Vaxin’s study involved 48 people that were divided into 3 groups of 16. Each group of 16 received a different dose of the vaccine on the first day and then received a second administration of a second dose 28 days later. Within each group of 16, only 12 people actually receive the vaccine and 4 people receive a placebo. Until the end of the study, no one knows who received the vaccine and who received the placebo.

STEVE: The mortality rates for H5 influenza have been between 30% and 70%. Did this lead you to choose H5 as a focus for your pre-pandemic vaccine?

BILL: The focus on H5 as a target for pre-pandemic vaccines is a result of the high degree of mortality seen in those that have been infected with the virus. While the 1918 flu had a catastrophic impact on the world and a large loss of life, it is estimated that the mortality rate was about 2%. However, it was able to spread very rapidly. Similarly, other pandemics from H2 and H3 outbreaks had relatively low mortality rates (estimated to be between 0.1%-0.5% for both the 1957 and 1968 pandemics).

STEVE: Can you speak about the delivery system you are using to deliver this vaccine?

BILL: Vaxin’s technology includes the use of another virus called adenovirus. This is a virus commonly found in nature which typically causes mild respiratory illnesses or cold like symptoms. It has a natural ability to infect humans at a very high rate. We have modified this virus so that it can no longer reproduce and we have incorporated a very small piece of the flu virus into the adenovirus. The adenovirus then infects people like normal but instead of making more adenovirus, it makes a piece of the flu virus. The body sees this in the same way it sees the flu…as a bad foreign protein and jump starts the immune system to get rid of it. In addition, our vaccine is given intranasally, the same way that the body normally sees both adenovirus and the flu. We believe the body responds in a very similar fashion in identifying and clearing the potential threat.

STEVE: Too many suffered complications to the H1N1 Swine Flu vaccine rushed through production in 1976; this leads me to ask if any corners would need to be cut, in terms of patient safety, to get a swine flu vaccine ready in time this year?

BILL: I am not familiar enough with the issues associated with moving the 1976 swine flu vaccine through the process to know about shortcuts taken, but the issues identified may still be issues. The result however was a significantly higher incidence of Guillain-Barre Syndrome (GBS) in those vaccinated vs those unvaccinated; 13.3 vs 2.6 per millions of people contracting Guillain-Barre, respectively. Note, significantly larger safety studies than are typically done for influenza vaccines would have been required to detect this event.

The current H1N1 swine flu vaccine would be against a very similar antigen and made with similar technologies for the most part and therefore the risk of GBS may still be prevalent. This will be weighed as a risk/benefit calculation when deciding how to proceed. It will depend in large part on the true mortality rate of the H1N1 swine flu vaccine. This was originally estimated at about 10%, but as identified cases of H1N1 and associated deaths are “confirmed” as opposed to being “probable” cases and the reporting becomes more accurate, it is now about 1% and falling. At 10% it is likely worth the calculated risk of GBS but at what point does the risk of death have a higher impact than the potential risk of GBS

STEVE: What percentage of health care workers, in our country, typically receive a flu shot?”

BILL: Only 36% of health care workers in the U.S. on average receive an influenza vaccine annually. (Source: CDC. Prevention and control of influenza: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR. 2003; 52 (RR8): 1-44.) Therefore, with a disease that can be spread two or more days before a person is symptomatic, an individual healthcare worker has a tremendous opportunity to spread the disease, without knowing it, to a population that is likely very susceptible, those that are sick and immune compromised to begin with.

STEVE: Do you have any suggestions for my colleagues and friends who tell me they get the flu from a flu shot?

BILL: It is scientifically not feasible to get the flu from a flu shot unless the vaccine has not been made appropriately and tested adequately. The licensed influenza vaccines on the market today are primarily inactivated whole virus or split subunit vaccines. Essentially the flu virus is grown in chicken eggs, purified and inactivated by heat or chemicals. The virus is unable to replicate and therefore cannot cause the flu. Usual side effects from any vaccination, because of the stimulation of a robust immune response from the body, include symptoms that some people associate with the flu, e.g., fever, body aches, sniffles etc. These symptoms are typical of many vaccinations including flu. Similarly in the new live virus vaccine (FluMist ®), the virus has been adapted to grow only in a cold environment. Once in the body its ability to replicate is severely limited and again not feasible to cause the flu.

All in all vaccines are the most cost effective medical procedure invented. Their use over the past century has saved millions of lives and untold expense with several previously common diseases now relatively under control or near complete eradication. Many people do not realize the annual cost, in lives lost, hospitalizations and subsequent economic costs, that influenza outbreaks inflict. Our ability to track and monitor influenza outbreaks and continual improvements in technologies and manufacturing processes are allowing us to attack influenza with the same vigor. While the world is more prepared than ever before to deal with potential pandemic influenza outbreaks, we still have room for improvement to ensure adequate, rapid access in all parts of the world. Vaxin is hopeful that our technologies and products will continue to advance this effort for rapidly available, safe, effective, easy to administer vaccines.

April 29th, 2009 by AlanDappenMD in Primary Care Wednesdays, Uncategorized

Tags: Doctokr, Doctokr Family Medicine, Dr. Alan Dappen, Primary Care, Primary Care Medicine, Primary Care Provider, Primary Care Wednesdays, Remote Access Visits, Telemedicine, telephone v

3 Comments »

In early 2006, four years into running my current medical practice, doctokr Family Medicine, I got a call from my medical malpractice carrier. Just weeks before I’d received a notice that my malpractice rates could go up by more than 25%. The added news of a pending investigatory audit was chilling. In 25 years of practicing medicine I’d never been audited.

“Is there a complaint, or a law suit against me that I don’t know about?”

“No,” the auditor told me over the phone, “We’ve never seen a medical practice like yours and feel obligated to investigate your process from a medical-legal perspective.”

“Great,” I thought, with a weary sigh. “I’m already battling the insurance model, the status quo of the medical business model, and slow adoption by consumers who are addicted to their $20 co-pay. All I’m trying to do is to breathe life into primary care and get the consumer a much higher quality service for less money than currently subsidized through the insurance model. And now this.”

The time had arrived to add the concerns of the malpractice companies to the list of hurdles to clear if a new vision of a medical care model was ever to catch flight.

I frequently am asked the question “Aren’t you afraid of the malpractice risk?” when I explain my medical practice model, which is based on the doctor answering the phone 24/7, resulting in the patient’s medical problem being solved by the phone more 50% of the time. The simplest counter to this question is to analyze the risk patients incur when the doctor won’t answer the phone. What happens when the doctor is the LAST person to know what’s going on with patients? The answer is obvious. But malpractice companies could have concerns beyond patient safety. Buy-in from the malpractice companies would be critical to the future viability of all telemedicine.

I prepared a summary paper, which included 12 bullet points, explaining how a doctor- patient relationship based on trust , transparency, continuous communications and high quality information systems significantly reduce risk to the person you’re trying to help.

Bullet 1: The industry standard is that 70% of malpractice cases in primary care center on communication barriers. My medical team deploys continuous phone and email communications and 7 days a week- same day office visits when needed between doctor and patient thus significantly reducing these barriers.

.

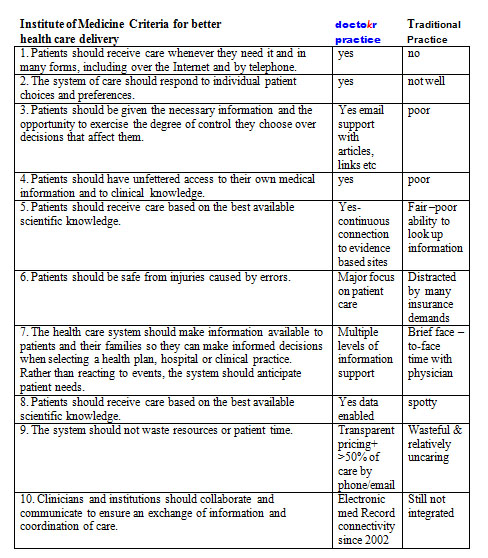

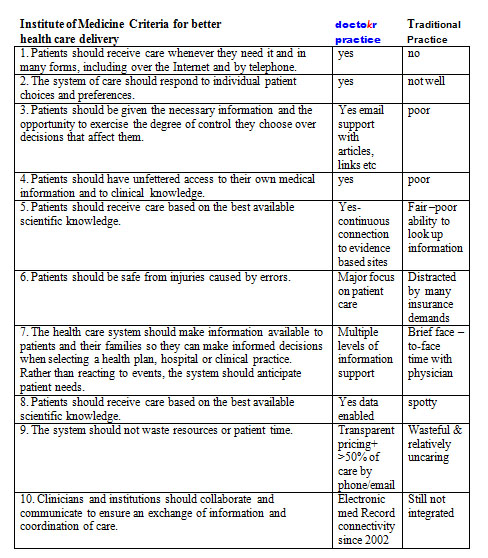

The remaining bullets could be summarized by the conclusions from the Institute of Medicine’s visionary book Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century using a table developed by The American Medical News when they reviewed the book. I carefully plotted our practice standards compared to the traditional business model as it stands today based on this table:

The auditor showed up, spent 4 hours reviewing our practice, electronic medical records, compliance to HIPPA, our intakes, on-line connectivity, procedures, and practice standards. While the auditor reviewed, I sat as unobtrusively as I could, feeling my brow grow damp with perspiration, as I carefully answered her questions. During the auditor’s time, I never moved to sway her to “my way.” I just let the data that I had accumulated from four years of practice do the talking.

Once the auditor left, I waited for two weeks for the results. By the time their letter arrived, I was scared to open it. The news arriving made me jubilant. The medical practice company announced a DECREASE in my premiums because we used telemedicine and EMR to treat patients so fast (often within 10 minutes of someone calling us we have their issue solved without the patient ever having to come in).

I will admit that I felt, and actually still do feel, vindicated by having my malpractice insurer understand fully the value that the type of telemedicine my practice offers to our patients: round-the-clock access to the doctor, speed of diagnosis, and convenience, which all led to healthier patients and lower risk.

Doctors answering the phone all day for their patients, it’s not just lower risk, it’s better health care at a better price. It’s a win-win-win strategy whose day is arriving.

Until next week, I remain yours in primary care,

Alan Dappen, MD

April 22nd, 2009 by AlanDappenMD in Primary Care Wednesdays

Tags: Doctokr Family Medicine, House Calls, Primary Care, Primary Care Wednesdays, Valerie Tinley

No Comments »

By: Valerie Tinley, MSN, RNFA, FNP-BC

House calls have long been associated with primary care providers (PCPs), the proverbial “black bag,” and days gone by. Unfortunately, house calls are often just a memory or something we watch in reruns on the television.

Those people that best remember the prevalence of house calls, the elderly, may be the same population whose needs will bring house calls back from the brink of extinction and return them to the mix of services offered by PCPs.

House calls should be a core offering of PCPs, since by nature we help patients from cradle to grave. Therefore, some of these patients may not be able to come to see us because they are too old or too sick or immobile.

Why then can’t PCPs go to these patients? We certainly can solve the majority of primary care problems where our patients want or need to be seen, including in their homes, whether these problems are run of the mill day-to-day issues; or those associated with chronic, continuous care diseases; or even many urgent care issues.

Unfortunately house calls are rarely offered because many PCPs view them as too time consuming and therefore too costly to conduct.

The need for house calls for these populations will not go away. The populations that house calls can help include:

• those that are bed bound, very old, who want to age at home rather than a nursing home;

• those suffering from dementia;

• those recently discharged from the hospital, and unable to be mobile short term or long term; and

• those that are receiving hospice care.

Many of these people cannot leave their home, or more importantly, should not leave the home, to go to the doctor’s office for an office visit. It is important to understand how very expensive this is for the caregiver, in terms of time, lost hours on the job, effort and transportation costs, all to actually get them to the medical provider’s office, because their loved ones have problems with mobility or other hindrances.

The result? There are many in need of medical care that cannot receive it. This increases medical problems and mortality. When healthcare is ignored or foregone for the most routine of problems, more expensive and much more serious healthcare issues arise in its place.

A recent article in the New York Times reported that keeping geriatric patients out of the hospital and getting them the care the need at home can result in a cost savings of between 30% and 60%. In addition, a house call program, piloted by Duke University, has reduced the number of hospital admissions for those patients unable to get to the doctors office by 68% and the number of emergency room admissions by 41%. These patients are thereby healthier, and even safer, working with a PCP that makes house calls.

Several organizations currently offer house calls as a core part of their services offerings, like Urban Medical in Boston, or the practice I am with, doctokr Family Medicine. Also there are beginnings of pilot programs for house calls, like the one at Duke’s Medical School which was mentioned earlier.

But these are only a few providers, and the movement needs to be widespread. Our aged population needs it and we as primary care providers should be listening to their needs and providing for these needs. Otherwise, we are falling short.

Until next week, I remain yours in primary care,

Valerie Tinley MSN, RNFA, FNP-BC