April 29th, 2009 by AlanDappenMD in Primary Care Wednesdays, Uncategorized

3 Comments »

In early 2006, four years into running my current medical practice, doctokr Family Medicine, I got a call from my medical malpractice carrier. Just weeks before I’d received a notice that my malpractice rates could go up by more than 25%. The added news of a pending investigatory audit was chilling. In 25 years of practicing medicine I’d never been audited.

“Is there a complaint, or a law suit against me that I don’t know about?”

“No,” the auditor told me over the phone, “We’ve never seen a medical practice like yours and feel obligated to investigate your process from a medical-legal perspective.”

“Great,” I thought, with a weary sigh. “I’m already battling the insurance model, the status quo of the medical business model, and slow adoption by consumers who are addicted to their $20 co-pay. All I’m trying to do is to breathe life into primary care and get the consumer a much higher quality service for less money than currently subsidized through the insurance model. And now this.”

The time had arrived to add the concerns of the malpractice companies to the list of hurdles to clear if a new vision of a medical care model was ever to catch flight.

I frequently am asked the question “Aren’t you afraid of the malpractice risk?” when I explain my medical practice model, which is based on the doctor answering the phone 24/7, resulting in the patient’s medical problem being solved by the phone more 50% of the time. The simplest counter to this question is to analyze the risk patients incur when the doctor won’t answer the phone. What happens when the doctor is the LAST person to know what’s going on with patients? The answer is obvious. But malpractice companies could have concerns beyond patient safety. Buy-in from the malpractice companies would be critical to the future viability of all telemedicine.

I prepared a summary paper, which included 12 bullet points, explaining how a doctor- patient relationship based on trust , transparency, continuous communications and high quality information systems significantly reduce risk to the person you’re trying to help.

Bullet 1: The industry standard is that 70% of malpractice cases in primary care center on communication barriers. My medical team deploys continuous phone and email communications and 7 days a week- same day office visits when needed between doctor and patient thus significantly reducing these barriers.

.

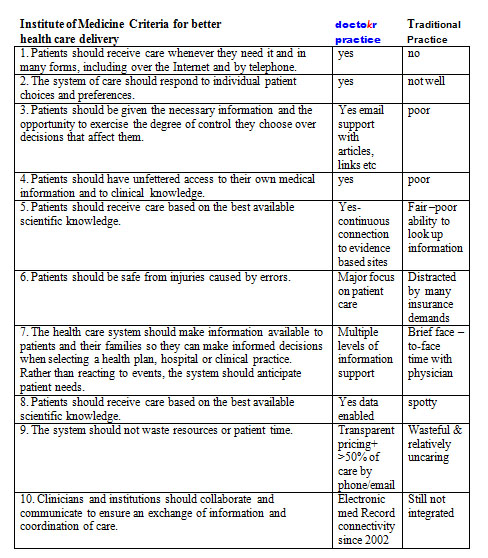

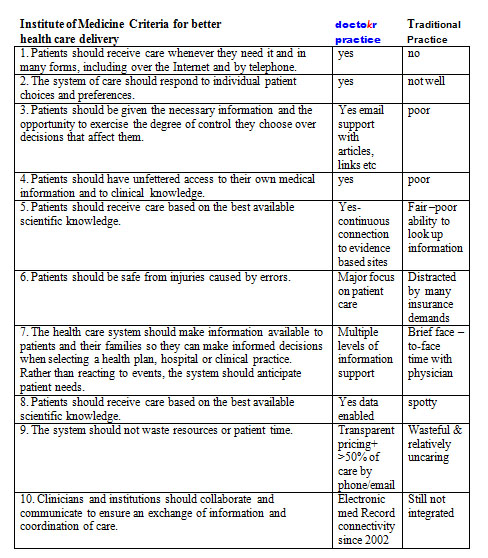

The remaining bullets could be summarized by the conclusions from the Institute of Medicine’s visionary book Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century using a table developed by The American Medical News when they reviewed the book. I carefully plotted our practice standards compared to the traditional business model as it stands today based on this table:

The auditor showed up, spent 4 hours reviewing our practice, electronic medical records, compliance to HIPPA, our intakes, on-line connectivity, procedures, and practice standards. While the auditor reviewed, I sat as unobtrusively as I could, feeling my brow grow damp with perspiration, as I carefully answered her questions. During the auditor’s time, I never moved to sway her to “my way.” I just let the data that I had accumulated from four years of practice do the talking.

Once the auditor left, I waited for two weeks for the results. By the time their letter arrived, I was scared to open it. The news arriving made me jubilant. The medical practice company announced a DECREASE in my premiums because we used telemedicine and EMR to treat patients so fast (often within 10 minutes of someone calling us we have their issue solved without the patient ever having to come in).

I will admit that I felt, and actually still do feel, vindicated by having my malpractice insurer understand fully the value that the type of telemedicine my practice offers to our patients: round-the-clock access to the doctor, speed of diagnosis, and convenience, which all led to healthier patients and lower risk.

Doctors answering the phone all day for their patients, it’s not just lower risk, it’s better health care at a better price. It’s a win-win-win strategy whose day is arriving.

Until next week, I remain yours in primary care,

Alan Dappen, MD

March 25th, 2009 by SteveSimmonsMD in Primary Care Wednesdays

No Comments »

Anyone working in healthcare has a moral responsibility to do the right thing, for the right reasons, and at a reasonable price; however, this is not happening. Today’s healthcare system is too expensive and it is broken. If it wasn’t broken, the current administration would not be focusing so much money and effort on fixing it. Likewise, 42 million Americans would not be uninsured creating two different standards of care within our country. Many decisions have already been made: providing government backed insurance coverage for the uninsured, encouraging the use of electronic health records systems (EHRs), and creating comparative effectiveness research boards (CERs). Much of what has been suggested sounds good but was passed by our legislature before seeking the input of those responsible for implementing these new policies and plans. Fortunately, President Obama’s administration is seeking input now and it is the responsibility of anyone working within the healthcare system to speak up and be heard.

Many hard-to-answer questions should have been asked before solutions were posed. Why is healthcare so expensive? How can the intervention of government lead us to better and more affordable healthcare? Although integrated EHR systems may prevent the duplication of tests and procedures, how can medical practitioners best use these systems to prevent mistakes? How will future decisions be made – between doctor and patient, or will the new CER Boards grow to do more than merely advise? How would the American people react to more controversial ideas, such as health care rationing to control exorbitant costs incurred at the end of life?

In my last post, I closed with a promise to share some ideas regarding healthcare reform. First, we should try to reach a consensus as to what is broken before implementing solutions. In Maggie Mahar’s book, Money-Driven Medicine (2006), her concluding chapter is titled, “Where We Are Now: Everybody Out of the Pool.” This title screams for change as she makes a convincing argument that all parties involved in healthcare need to rethink how we can work together to fix a broken healthcare system which seems focused, not on healthcare, but on money. Today, Uncle Sam has jumped into the pool feet first, creating quite the splash, and he is spending large sums of money to lead healthcare reform without first reaching a consensus as to what is broken in this system.

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 will direct $150 billion dollars to healthcare in new funds, with most of it being spent within two years. Health information technology will receive $19.2 billion of these dollars, with the lion’s share ($17.2 billion) going towards incentives to physicians and hospitals to use EHR systems and other health information technologies. According to the New England Journal of Medicine, the average physician will be eligible for financial incentives totaling between $40,000 and $65,000; this money will be paid out to physicians for using EHRs to submit reimbursement claims to Medicare and Medicaid, or for demonstrating an ability to ‘eprescribe’. This money will help offset the cost of implementing a new EHR, which can cost between $20,000 and $50,000 per year per physician. However, after midnight, December 31, 2014, this “carrot” will turn into something akin to Cinderella’s pumpkin, becoming a “stick” that will financially penalize those physicians and hospitals not using EHRs in a “meaningful” way.

At our office, doctokr Family Medicine, we use an EHR, but consider it a tool, much like a stethoscope or thermometer, used to facilitate the doctor-patient relationship, not a tool to track our reimbursement activities. I would not argue against EHRs, but there is no evidence they will make healthcare more affordable and improve the quality of care delivered – unless you believe the $80 billion dollar a year savings “found” in the 2005 RAND study (paid for by companies including Hewlett-Packard and Xerox- incidentally, companies developing EHRs). I believe it will take far more than EHRs, financial incentives, and good data to fix our broken healthcare system.

Difficult decisions await those willing to ask the hard questions but don’t expect any easy answers to present themselves on the journey towards effective healthcare reform. My partner and I believe we have found answers to some questions and are moving forward, in our own practice, now. Asking why healthcare is so expensive and feeling frustrated with the high cost of medical software, we have written our own EHR, containing costs for our patients by keeping down our overhead expenses. Our financial model is based on time spent with the patient, not codes and procedures, which helps us to avoid ‘gaming’ the system and wasting time.

A familiar adage states that there are no problems, only solutions. I suggest, though, that there can be no solutions without problems. Find the right questions and opportunities abound. Earlier in this post, I asked how government intervention can lead us to better and more affordable healthcare. It can’t, at least not without the help and guidance of doctors, patients, industry, insurance companies, hospitals, and anyone who understands what is at stake with health care reform. We all share in the responsibility to try.

Until next week, I remain yours in primary care,

Steve Simmons, MD

March 18th, 2009 by AlanDappenMD in Primary Care Wednesdays

9 Comments »

The U.S. government finally has announced intentions to become involved in our $2.2 trillion healthcare system. Now everyone wants to say something. Most longtime players in healthcare indignantly rebut any new input and opinions with “How dare you! … You stay away from my holy cow of entitlements (insured patients), or salary (doctors), or bonuses (insurance companies), or profits (pharmaceutical companies), or the ability to sue (lawyers.)”

I join my voice to President Obama’s statement that the single most important problem to solve in our healthcare systems is cost. The tidal wave of catastrophe rushing towards America is the expenditure of healthcare dollars doubling every 7-10 years.

Few will argue against the ideal of universal health coverage, yet this noble ideal comes with an enormous price tag and many less than honorable behaviors by all players in the system. The wasted and misallocated money lost every year in healthcare makes Madoff’s Ponzi scheme look like child’s play, and yet it continues. We finally have awoken the dormant giant of politicians to do what no one else says they will do, and the government’s intervention in the form of healthcare reform seems imminent.

Doctors were captains of the healthcare system until 1980s. They were dethroned because health care costs had doubled every seven years since 1945. Then insurance companies gladly took the helm. Guess what? After 20 year of their leadership, the price of healthcare has continued to double on average of every 10 years. Now the government is positioned to step in and fix it.

Big Brother might “force” each of us healthcare players to be held accountable including all of us as patients. This fear of change leads to finger pointing, name calling, blaming, grandstanding, and claiming, “Oh the ridiculous price healthcare … it’s not my fault and I shouldn’t have to change or fix it.” Nothing could be further from the truth. We all have to fix healthcare, and never forget, it’s about the price.

How do we create a health care system that provides the widest access, the best bang for the buck, the fairest distribution of money, and inflates at the same speed as the rest of the economy?

For primary care, two pathways are clear: the career path or the professional practitioner path. With the career model, doctors can work for someone else (like Kaiser, Medicare, an insurance company, or a hospital), and can expect a salary and benefits. In return, these employers oversee and influence how career doctors do their jobs, their hours, their interactions with patients, how they communicate with patients, and often what medications should be prescribed. We have 20 years of experience with the “career pathway.” We allowed others to interfere in the doctor patient relationship, help us ”manage” our patients, and decide what’s “reimbursable.” The soul of our work and the trust of our patients evaporated. Many believe this pathway will spell the extinction of the primary care “specialist.”

The other pathway is the primary care doctor as a professional, with a mission that focuses on the patient not just for quality, but for trust and price, and following these key objectives:

- Restoring the soul and viability of the doctor patient relationship,

- Delivering the highest quality care, and

- Restoring a pricing integrity which reduces cost.

This professional primary care doctor will restore the patient-doctor relationship with a modern office that is mobile, can be reached anywhere and anytime, has virtually no staff, minimal overhead costs, transparent pricing, and is powered through a customized software that finds the patient chart, instantly looks up any pharmacy or radiology center, can contact any specialist, can instantly look at differentials, drug interactions, gets notifications when patients have something “due,” has a large number of patient education resources that can be emailed to the patient including articles from the medical literature and refereed internet sites that can educate patients, and does all the billing from the same platform the moment that the note is closed.

An individual’s day-to-day health is not “best managed” under third-party payers. We need insurance or government to manage expensive problems or catastrophe, like cancer, serious injuries or ongoing health problems. Yet sixty years of conditioning has left most unable to see the obvious: extract the day-to-day care cost from the insurance model and return these funds to all Americans (about $700 billion/year), stop holding the consumer hostage, make doctors compete again for the consumer on price, quality, knowledge, access, convenience, relationship — just like every other service industry. Finally, bring an end the $20 co-pay mentality for the patient and “the funnel” for the doctor.

This is possible, and is being done today with the practice I founded, doctokr Family Medicine, (www.doctokr.com). Our patients pay out-of-pocket for all the primary and urgent care healthcare services they receive. We charge on a transparent time-based fee basis, where five minutes of the doctor’s time costs around $25. Our patients can contact or see us anytime, day or night, and consult with us via phone, email, in our offices or by house calls, with over 50% of all of our patients’ healthcare issues being resolved by phone or email. About 75% of our patients pay less than $300 per year for all of their primary and urgent care needs. We’ve built a relationship with each patient and spend as much time as they want with us.

In the weeks ahead I invite all readers and colleagues to consider the road less traveled. Consider primary care doctors standing-up, reclaiming their profession, embracing and being embraced by the American population. And imagine happier patients and doctors, healthier patients and that the delivery of that care costs 50% less than now.

Until next week, I remain yours in primary care,

Alan Dappen, MD

March 11th, 2009 by SteveSimmonsMD in Primary Care Wednesdays

3 Comments »

Over the centuries, many societies have elevated the medical profession in thought and deed. Not that long ago this was true in the U.S., when our citizens showed more respect for doctors as professionals and fellow citizens than is demonstrated today. Now, everyone seems to agree that healthcare reform is drastically needed, and many are speaking out. Yet, the frank indifference to the opinions of doctors by those outside the medical profession mutes the voice and counsel of doctors on the subject. The AMA (American Medical Association) and many other physician groups are speaking out on reform, but their voice is diluted by a cacophony of assumptions, opinions, and by legislation existing and proposed. A new healthcare system has been formed, in large part, without seeking the input of those needed to make it work: practicing physicians.

Recently, I overheard a discussion regarding healthcare reform while eating lunch at a local restaurant. The debate hinged on who is most qualified to make healthcare-related decisions. The following consensus was reached: no one today should complain about the government taking over healthcare because allowing insurance companies to make all the decisions in the past resulted in a broken healthcare system. Those surrounding this particular lunch table agreed that the time had come for government to have their turn, while opposition could best be characterized as siding with the insurance companies. I wonder: can the debate really be so simply framed?

Saddened by the realization that such a discussion could be loudly and passionately debated without mentioning doctors, I resisted the urge to point out that physicians had made the healthcare decisions before insurance companies gained control. The fact physicians were not even mentioned attests to the sad truth that for many people doctors are merely seen as one part of a broken healthcare machine. Most physicians see their lot differently, and consider themselves as being in a veritable state of conflict with health insurance companies; however, our participation in a failing healthcare system has afforded these very same companies with the opportunity to put physician’s faces on their failed practices, with public opinion supporting this assumption.

Regardless of your opinion on Medicare, this last major government intervention into healthcare can help illustrate the very point that I am trying to make. On May 20, 1962, President Kennedy argued for Medicare, addressing a crowd of 20,000 at Madison Square Garden. The President was televised gratis by the three major networks reaching an additional 20 million people in their homes. Two days later, the AMA rebutted his argument, purchasing thirty minutes on NBC, with their speaker reaching an estimated audience of 30 million people. This broadcast, more far-reaching and influential than the President’s, delayed the proposed Medicare system by several years. Forty-seven years ago, people in this country wanted to know what doctors had to say before major decisions regarding healthcare were made. Today, they do not.

As the discussion about healthcare reform continues, practicing physicians must be heard from to interject real medical experience into the debate and, hopefully, guide the future of healthcare by influencing legislation existing and proposed. I am trying to remain optimistic despite the concern I feel in noting that the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, section 3000 (pages 511, 518, 540-541) exemplifies the minimization of medical practitioners, using terminology like “Meaningful” ‘USERS’ to describe physicians.

The question is now raised: what should medical practitioners do to be heard, to influence healthcare reform, to play a leadership role in this time of change? When I write next time; I will share some of our ideas, put them on the table, if you will. But, I would encourage you to proffer those suggestions that you might have. It appears we can either speak up now or choose to be “meaningful” later.

Until next week, I remain yours in primary care,

Steve Simmons, MD

January 14th, 2009 by Dr. Val Jones in Primary Care Wednesdays

No Comments »

By Steve Simmons, M.D.

By Steve Simmons, M.D.

Gordian Knot: 1: an intricate problem ; especially : a problem insoluble in its own terms —often used in the phrase cut the Gordian knot 2: a knot tied by Gordius, king of Phrygia, held to be capable of being untied only by the future ruler of Asia, and cut by Alexander the Great with his sword

Generations ago, the American Medical Association’s (AMA) Code of Ethics stipulated that allowing a third party to profit from a physician’s labor was unethical. This tenet resides in a time when house calls were common place; when trust and respect helped forge an immutable bond between doctor and patient; and when it would have been unthinkable to allow anyone other than the doctor, family, or patient to have a role within the doctor-patient relationship.

The landscape of today’s healthcare system and its delivery methods make the authors of the AMA’s forgotten code look prescient. Insurance companies, controlling the purse strings, have become an unwelcome partner within the doctor-patient relationship, frequently dictating what can and can’t be done, and are reaping a healthy profit from their oversight. Obscene salaries and large bonuses are awarded to the CEOs of these companies for keeping as much money as they can from those providing health services, with the CEO United Healthcare being reported as receiving a $324 million paycheck during a five year period. Thus, short-term business strategies are given priority, often at the expense of patients’ long-term medical goals, creating a Gordian knot so entwined that no one – patients, doctors, insurance providers, or government regulators – can see a way to unravel it.

A result of so much money being skimmed off the top is that no one seems to be getting what they need, let alone want. Patients long for more time to discuss problems with their doctor and wish it were easier to get an appointment. Yet physicians are unable to receive adequate reimbursement from insurance companies for their services, and if they do get reimbursement, it’s after months of waiting and often at the high expense of having a posse of back office staff needed to negotiate these payments. These physicians therefore are forced to overload their schedule and rapidly move patients through their office if they are to earn their typical $150,000 per year, pay off medical school debt, and afford the salaries of their office employees. Finally, government agencies, looking for the elusive loop to tug on, ultimately burden physicians further with a myriad of onerous rules and regulations.

Read more »