August 17th, 2015 by Dr. Val Jones in True Stories

26 Comments »

If you have not read the latest essay and editorial about scandalous physician behavior published in the Annals of Internal Medicine (AIM), you must do so now. They describe horrific racist and sexist remarks made about patients by senior male physicians in front of their young peers. The physicians-in-training are scarred by the experience, partially because the behavior itself was so disgusting, but also because they felt powerless to stop it.

If you have not read the latest essay and editorial about scandalous physician behavior published in the Annals of Internal Medicine (AIM), you must do so now. They describe horrific racist and sexist remarks made about patients by senior male physicians in front of their young peers. The physicians-in-training are scarred by the experience, partially because the behavior itself was so disgusting, but also because they felt powerless to stop it.

It is important for the medical community to come together over the sad reality that there are still some physicians and surgeons out there who are wildly inappropriate in their patient care. In my lifetime I have seen a noticeable decrease in misogyny and behaviors of the sort described in the Annals essay. I have written about racism in the Ob/Gyn arena on my blog previously (note that the perpetrators of those scandalous acts were women – so both genders are guilty). But there is one story that I always believed was too vile to tell. Not on this blog, and probably not anywhere. I will speak out now because the editors at AIM have opened the conversation.

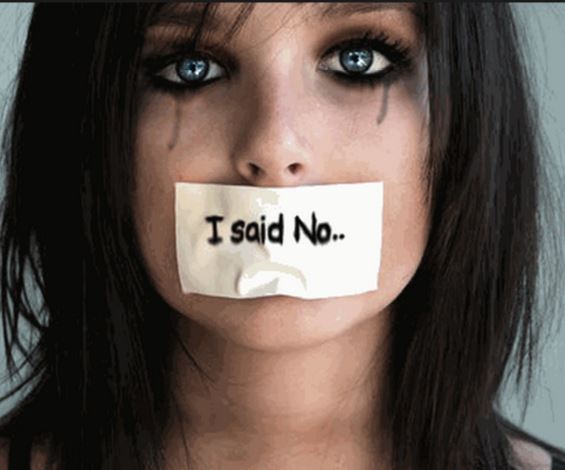

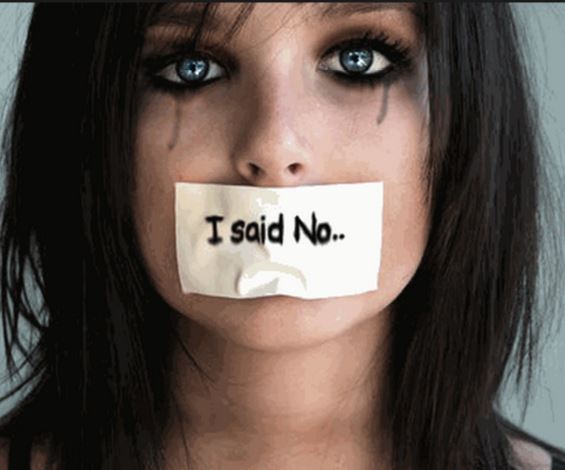

When I was a third-year medical student I was assigned to tag along with an ophthalmology resident serving his first year of residency as an intern in general surgery. We were to cover the ER consult service one night, and our first patient was a young Hispanic girl with abdominal pain. It was suspected that she may have had appendicitis. Part of the physical exam required that we rule out a gynecologic cause of the pain. And so a pelvic exam was planned for this young girl of about 12 or 13. She was frightened and clinging to her grandmother. She had never seen a gynecologist before and had explained through her grandmother that she was a virgin – making a gynecologic cause of her abdominal pain less likely. I offered her some reassurance with my broken Spanish and held her hand as we wheeled her on a stretcher to a private examining room. The resident whispered in my ear, “This is going to be fun.”

The resident was creepy at every stage of the exam. He was clearly relishing the process, slowly instructing the poor girl to position herself correctly on the table. He held her knees apart as she whimpered and cried. He pretended to have difficulty positioning the speculum, inserting and reinserting it an unconscionable number of times. All-in-all it probably took ten minutes for him to get a cervical sample (this usually takes under 60 seconds). He performed the bi-manual portion of the exam in a bizarre, sexualized manner. I was furious and nauseated.

The patient was finally returned to her grandmother and the resident took me aside to ask how I thought he did. The perverted expression on his face was not lost on me. I looked at him with daggers in my eyes, but I knew that if I confronted him head-on it could trigger an investigation and in the end I had no hard evidence to prove that he had done anything wrong. It would wind up being a “he said, she said” scenario. I mustered the courage to say, “I think you were slow.”

For a fleeting moment he was taken aback by my insubordinate criticism and then he said the sentence that still haunts me today, “Well it was her first time.”

Each time I think of this interaction I feel sick to my stomach. I wonder what more I could have done.* I wonder if he is still out there violating his patients, and if anyone has ever confronted him. My only consolation, I suppose, is that he did not go on to become an Ob/Gyn. As an ophthalmologist one would hope that he had fewer opportunities for sexual abuse of patients.

I guess you could say that in my medical training, I witnessed a child rape. I don’t think it gets much worse than that… and I don’t know what to do with this horrific memory. I am forever changed.

It is my hope that these sorts of situations become true “never events” and that we create a protective environment where there are no career consequences for medical students thrust into the unfortunate position of whistle blower. Maybe the courageous AIM editorial is the first step towards redemption and healing.

*Note that I never saw this resident again. Our paths did not cross after the incident, and it was only at the end of the exam that I fully recognized the evil of his intent.

April 15th, 2009 by DrRich in Better Health Network

7 Comments »

DrRich thanks the Cockroach Catcher (his favorite retired child psychologist) for pointing him to an article (by Mark Wicclair, a bioethicist) and an accompanying editorial (by Deborah Kirklin, a primary care physician) in the peer-reviewed medical journal, Medical Humanities, which deconstruct the television show “House MD.”

A TV show may at first glance seem a strange subject for a medical journal, but this is, after all, a journal whose subject is the “softer” side of medical science. (DrRich hopes his friend the Cockroach Catcher will take no offense at this characterization, and directs him, in the way of an apology, to the recent swipes DrRich has taken at his own cardiology colleagues for their recent sorry efforts at “hard” medical science.) Besides, the Medical Humanities authors use the premise and the popularity of “House MD” to ask important questions about medical ethics, and the consequent expectations of our society.

DrRich does not watch many television shows, and in particular and out of general principles he avoids medical shows. But he has seen commercials for House, and has heard plenty about it from friends, so he has the gist of it. The editorial by Dr. Kirklin summarizes:

“[House] is arrogant, rude and considers all patients lying idiots. He will do anything, illegal or otherwise, to ensure that his patients—passive objects of his expert attentions—get the investigations and treatments he knows they need. As Wicclair argues, House disregards his patients’ autonomy whenever he deems it necessary.”

Given such a premise, the great popularity of “House MD” raises an obvious question. Dr. Kirklin:

“… why, given the apparently widely-shared patient expectation that their wishes be respected, do audiences around the world seem so enamoured of House?”

Indeed. While it has not always been the case, maintaining the autonomy of the individual patient has become the primary principle of medical ethics. And medical paternalism, whereby the physician knows best and should rightly make the important medical decisions for his or her patient, is a thing of the past.

It has been formally agreed, all over the world, that patients have a nearly absolute right to determine their own medical destiny. In particular, unless the patient is incapacitated, the doctor must (after taking every step necessary to inform the patient of all the available options, and the potential risks and benefits of each one) defer to the final decision of the patient – even if the doctor strongly disagrees with that decision. Hence, the kind of behavior which is the modus operandi of Dr. House should be universally castigated.

So, the question is: Given that House extravagantly violates his patients’ autonomy whenever he finds an opportunity to do so, joyfully proclaiming his great contempt for their individual rights, then why is his story so popular? And what does that popularity say about us?

To DrRich, the answer seems quite apparent.

The notion that the patient’s autonomy is and ought to be the predominant principle of medical ethics, of course, is entirely consistent with the Enlightenment ideal of individual rights. This ideal first developed in Europe nearly 500 years ago, but had trouble taking root there, and really only flowered when Europeans first came to America and had the opportunity to put it to work in an isolated location, where rigid social structures were not already in place. The development of this ideal culminated with America’s Declaration of Independence, in which our founders declared individual autonomy (life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness) to be an “inalienable” right granted by the Creator, and thus predating and taking precedence over any government created by mankind. And since that time the primacy of the individual in American culture has, more or less, remained our chief operating principle. Individual autonomy – or to put it in more familiar terms, individual freedom – is the foundational principle of our culture, and it is one that is perpetually worth fighting and dying to defend.

So the idea that the autonomy of the individual ought rightly to predominate when it comes to making medical decisions is simply a natural extension of the prime American ideal. Of course, most think, this ought to be the governing principle of medical ethics.

But unfortunately, it’s not that easy. There’s another principle of medical ethics that has an even longer history than that of autonomy – the principle of beneficence. Beneficence dictates that the physician must always act to maximize the benefit – and minimize the harm – to the patient. Beneficence recognizes that the physician is the holder of great and special knowledge that is not easily duplicated, and therefore has a special obligation to use that knowledge – always and without exception – to do what he knows is best for the patient. Dr. House is a proponent of the principle of beneficence (though he is caustic and abrasive about expressing it). DrRich believes House is popular at least partly because the benefits that can accrue to a patient through the principle of beneficence – that is, through medical paternalism – are plain for all to see.

Obviously the principles of beneficence and of individual autonomy will sometimes be in conflict. When two worthwhile and legitimate ethical principles are found to be in conflict, that is called an ethical dilemma. Ethical dilemmas are often resolved either by consensus or by force. In our case, this dilemma has been resolved (for now) by consensus. The world community has deemed individual autonomy to predominate over beneficence in making medical decisions.

DrRich’s point here is that Dr. House (the champion of beneficence) is not absolutely wrong. Indeed, he espouses a time-honored precept of medical ethics, which until quite recently was THE precept of medical ethics. There is much to be said for beneficence. Making the “right” medical decision often requires having deep and sophisticated knowledge about the options, knowledge which is often beyond the reach of many patients. And even sophisticated patients who are well and truly medically literate will often become lost when they are ill, distraught and afraid, and their capacity to make difficult decisions is diminished. Perhaps, some (like House) would say that their autonomy ought not be their chief concern at such times. Indeed, one could argue that in a perfect world, where the doctor indeed has nearly perfect knowledge and a nearly perfect appreciation of what is best for the patient, beneficence should take precedence over autonomy.

It is instructive to consider how and why autonomy came to be declared, by universal consensus, the predominant principle of medical ethics. It happened after World War II, as a direct result of the Nuremberg Tribunal. During that Tribunal the trials against Nazi doctors revealed heinous behavior – generally involving medical “research” on Jewish prisoners – that exceeded all bounds of civilized activity. It became evident that under some circumstances (circumstances which under the Nazis were extreme but which were by no means unique in human history) individual patients could not rely on the beneficence of society, or the beneficence of the government, or the beneficence of their own doctors to protect them from abuse at the hands of authority. Thusly was the ethical precept which asks patients ultimately to rely on the beneficence of others starkly revealed to be wholly inadequate. The precept of individual autonomy, therefore, won by default.

Subsequently, the Nuremberg Code formally declared individual autonomy to be the predominant precept in medical ethics, and beneficence, while also important, to be of secondary concern. Where a conflict occurs, the patient’s autonomy is to win out. It is important to note that this declaration was not a positive statement about how honoring the autonomy of the individual represents the peak of human ethical behavior, but rather, it was a negative statement. Under duress, the Nuremberg Code admitted, societies (and their agents) often behave very badly, and ultimately only the individual himself can be relied upon to at least attempt to protect his or her own best interests.

DrRich will take this one step further. When our founders made individual autonomy the organizing principle of a new nation, they were also making a negative statement. From their observation of human history (and anyone who doubts that our founders were intimately familiar with the great breadth of human history should re-read the Federalist Papers), they found that individuals could not rely on any earthly authority to protect them, their life and limb, or their individual prerogatives. Mankind had tried every variety of authority – kings, clergy, heroes and philosophers – and individuals were eventually trampled under by them all. For this reason our founders declared individual liberty to be the bedrock of our new culture – because everything else had been tried, and had failed. In the spirit of the enlightenment they agreed to try something new.

There is an inherent problem with relying on individual autonomy as the chief ethical principle of medicine, namely, autonomous patients not infrequently make very bad decisions for themselves, and then have to pay the consequences. The same occurs when we rely on individual autonomy as the chief operating principle of our civil life. The capacity of individuals to fend for themselves – to succeed in a competitive culture – is not equal, and so the outcomes are decidedly unequal. Autonomous individuals often fail – either because of inherent personal limitations, bad decisions, or bad luck.

So whether we’re talking about medicine or society at large, despite our foundational principles we will always have the tendency to return to a posture of dependence – of relying on the beneficence of some authority, in the hope of achieving more overall security or fairness – at the sacrifice of our individual autonomy. In DrRich’s estimation the popularity of “House MD” is entirely consistent with this tendency. (Indeed, the writers almost have to make Dr. House as unattractive a person as he is, just to temper our enthusiasm for an authority figure who always knows what is best for us and acts on that knowledge, come hell or high water.)

Those of us who defend the principle of individual autonomy – and the economic system of capitalism that flows from it – all too often forget where it came from, and DrRich believes this is why it can be so difficult to defend it. We – and our founders – did not adopt it as the peak of all human thought, but for the very practical reason that ceding ultimate authority to any other entity, sooner or later, guarantees tyranny. This was true in 1776, and after observing the numerous experiments in socialism we have seen around the world over the past century, is even more true today.

Individual autonomy will always be a very imperfect organizing principle, both for healthcare and for society at large. Making it an acceptable principle takes perpetual hard work, to find ways of smoothing out the stark inequities, without ceding too much corrupting power to some central authority. This is the great American experiment.

Those of us who have the privilege of being Americans today, of all days, find ourselves greatly challenged. But earlier generations of Americans faced challenges that were every bit as difficult. If we continually remind ourselves what’s at stake, and that while our system is not perfect or even perfectable, it remains far better than any other system that has ever been tried, and that we can continue to improve on it without ceding our destiny – medical or civil – to a corruptible central authority, then perhaps we can keep that great American experiment going, and eventually hand it off intact to yet another generation, to face yet another generation’s challenges.

*This blog post was originally published at the Covert Rationing Blog.*

If you have not read the latest essay and editorial about scandalous physician behavior published in the Annals of Internal Medicine (AIM), you must do so now. They describe horrific racist and sexist remarks made about patients by senior male physicians in front of their young peers. The physicians-in-training are scarred by the experience, partially because the behavior itself was so disgusting, but also because they felt powerless to stop it.

If you have not read the latest essay and editorial about scandalous physician behavior published in the Annals of Internal Medicine (AIM), you must do so now. They describe horrific racist and sexist remarks made about patients by senior male physicians in front of their young peers. The physicians-in-training are scarred by the experience, partially because the behavior itself was so disgusting, but also because they felt powerless to stop it.