Leeches As Medical Devices: A Sordid History

What did the jockey who never lost a race whisper into the horse’s ear? “Roses are red, violets are blue, Horses that lose are made into glue!” OK, so it’s a groaner. But until the advent of polyvinyl acetate (PVA) and other synthetic glues in the twentieth century, the destiny of aging horses was indeed the glue factory. The collagen extracted from their hides, connective tissues and hooves made for an ideal wood adhesive. Our word “collagen” for the group of proteins found in these tissues actually derives from the Greek “kolla” for “glue.”

What did the jockey who never lost a race whisper into the horse’s ear? “Roses are red, violets are blue, Horses that lose are made into glue!” OK, so it’s a groaner. But until the advent of polyvinyl acetate (PVA) and other synthetic glues in the twentieth century, the destiny of aging horses was indeed the glue factory. The collagen extracted from their hides, connective tissues and hooves made for an ideal wood adhesive. Our word “collagen” for the group of proteins found in these tissues actually derives from the Greek “kolla” for “glue.”

Not all aging horses were dispatched to the glue factory after their plow-pulling days came to an end. Some farmers found they could squeeze a little more profit out of the animals by assigning them another duty. They would become leech collectors! The elderly horses were driven into swampy waters only to emerge coated with the little bloodsucking worms. It seems the creatures found horses to be a particularly tasty treat! Since for many people suffering from various ailments, the little parasites were just what the doctor ordered, the harvesting of leeches made for a lucrative business.

Leeches have actually been used in medicine since they were first introduced around 1500 BC by the Indian sage Sushruta, one of the founders of the Hindu system of traditional medicine known as “Ayurveda.” That translates from the Sanskrit as “knowledge of life.” Sushruta recommended that leeches be used for skin diseases and for various musculoskeletal pains. Ancient Egyptian doctors extended the indications, treating headaches, ear infections and even hemorrhoids in this peculiar fashion. Galen, the famous Roman physician, used leeches to balance the four “humors,” namely blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile. Swollen, red skin, for example, was thought to be due to too much blood in the body and the answer was to have leeches slurp the excess.

Curiously, despite having no evidence for efficacy, bloodletting, either with leeches or by making an incision with a “lancet,” became part of standard medical practice for more than 2500 years! Monks, priests and barbers got into the act along with physicians. In 1799 George Washington had more than half his blood drained in ten hours, certainly hastening his demise.

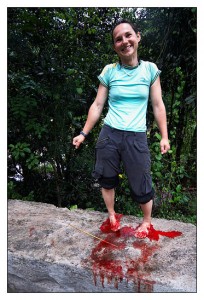

Many British doctors preferred leeches, especially in areas around the mouth, ears and eyes where lancing was a tricky procedure. They even learned how to encourage a leech to bite by stimulating its appetite with sugar or alcohol. But the creatures were in short supply, and had to be imported by the millions from France, Germany, Poland and Australia where they were often caught in nets using liver as bait. Sometimes poor children earned a little extra money by wading into infested waters to emerge, like the horses, with leeches attached to their legs. A gentle tug or a pass with a flame then relaxed the bloodsucker’s grip before much damage ensued. Good thing, because leeches can be pretty nasty once they latch on. Remember Humphrey Bogart flailing about in African Queen while trying to rid himself of the little vampires?

The lack of leeches caused some physicians to explore recycling techniques. Usually a single leech becomes satiated after filling up on about 15 milliliters of blood and then falls off. But then if it is plunked into salt water, it will disgorge the blood and is soon ready for another round. A German physician even developed a technique to encourage continued sucking by making an incision in the leech’s abdomen allowing for the ingested blood to drain out as fast as it came in. It seems the leech wasn’t much bothered by this affront to its belly and would go on sucking for hours. Amazingly, leeches were sometimes used internally. To treat swollen tonsils, a leech with a silk thread passed through its body would be lowered down the throat and withdrawn when it had finished its meal. Sometimes the creatures were even introduced into the vagina to treat various “female complaints.” The literature is vague about how this was done but one account suggests that the technique required a clever nurse.

While bloodletting as a general treatment for ailments has been drained out of the modern medicine chest, there is still work for leeches. That’s because their saliva is a complex chemical mix of pain killers and anticoagulants. Hirudin, for example, is the protein that keeps the blood flowing steadily after the initial bite is made, and is so effective that the blood will not coagulate for quite some time even after the leech falls off. Indeed, these bloodsucking aquatic worms have received approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Agency as a “medical device.”

Surgeons have been known to use leeches after reattaching ears, eyelids or fingers that have been severed, as well as after skin grafts. This has to do with the fact that arteries are easy to reconnect but veins are not. Eventually new capillaries do form to reconnect veins, but in the meantime the finger or ear fills with blood which then clots and causes problems with circulation. A leech will drain the excess blood at just the right rate and can prevent blood clot formation by injecting hirudin. This is such a potent anticoagulant that it holds hope for dissolving blood clots after a heart attack or stroke. Unfortunately hirudin is too difficult to extract from leeches but can potentially be produced through genetic engineering techniques.

Where do physicians get leeches today? No need for horses. They can order them directly from the French firm Ricarimpex. One would think that after helping to save a finger or an ear the useful little critters would be rewarded. But their destiny is death in a bucket of bleach. Not any better than ending up in a glue factory.

***

Joe Schwarcz, Ph.D., is the Director of McGill University’s Office for Science and Society and teaches a variety of courses in McGill’s Chemistry Department and in the Faculty of Medicine with emphasis on health issues, including aspects of “Alternative Medicine”. He is well known for his informative and entertaining public lectures on topics ranging from the chemistry of love to the science of aging. Using stage magic to make scientific points is one of his specialties.