March 2nd, 2011 by Jessie Gruman, Ph.D. in Better Health Network, Opinion

1 Comment »

The other day I came across this photo of a couple clasping each other in a dramatic tango on the cover of an old medical journal — a special issue from 1999 that was focused entirely on doctor-patient partnership. The tone and subjects of the articles, letters and editorials were identical to those written today on the topic: “It’s time for the paternalism of the relationship between doctors and patients to be transformed into a partnership;” “There are benefits to this change and dangers to maintaining the status quo;” “Some doctors and patients resist the change and some embrace it: Why?”

The other day I came across this photo of a couple clasping each other in a dramatic tango on the cover of an old medical journal — a special issue from 1999 that was focused entirely on doctor-patient partnership. The tone and subjects of the articles, letters and editorials were identical to those written today on the topic: “It’s time for the paternalism of the relationship between doctors and patients to be transformed into a partnership;” “There are benefits to this change and dangers to maintaining the status quo;” “Some doctors and patients resist the change and some embrace it: Why?”

Two questions struck me as I impatiently scanned the articles from 12 years ago: First, why are these articles about doctor-patient partnership still so relevant? And second, why did the editor choose this cover image?

I’ve been mulling over these questions for a couple days, and I think an answer to the second question sheds light on the first. Here are some thoughts about the relationship between patients and doctors (and nurse practitioners and other clinicians) evoked by that image of the two elegant people dancing together:

It takes two to tango. Ever seen one guy doing the tango? Nope. Whatever he’s doing out there on the dance floor, that’s not tango. Without both dancers, there is no tango. The reason my doctor and I come together is our shared purpose of curing my illness or easing my pain. We bring different skills, perspectives and needs to this interaction. When in a partnership, I describe my symptoms and recount my history. I talk about my values and priorities. I say what I am able and willing to do for myself and what I am not. My doctor has knowledge about my disease and experience treating it in people like me; she explains risks and tradeoffs of different approaches and tailors her use of drugs, devices, and procedures to meet my needs and my preferences. Both of us recognize that without the active commitment of the other we can’t reach our shared goal: To help me live as well as I can for as long as I can.

Each dancer adjusts to his or her partner. In tango, each partner has different moves; the lead shifts subtly and constantly between them throughout the dance. In a partnership, when I am really ill, I delegate more decisions to my physicians; when I am well we freely go back and forth, discussing treatment options and making plans. Read more »

*This blog post was originally published at CFAH PPF Blog*

January 21st, 2011 by DavedeBronkart in Health Tips, Opinion

No Comments »

There are several stages in becoming an empowered, engaged, activated patient — a capable, responsible partner in getting good care for yourself, your family, whoever you’re caring for. One ingredient is to know what to expect, so you can tell when things seem right and when they don’t.

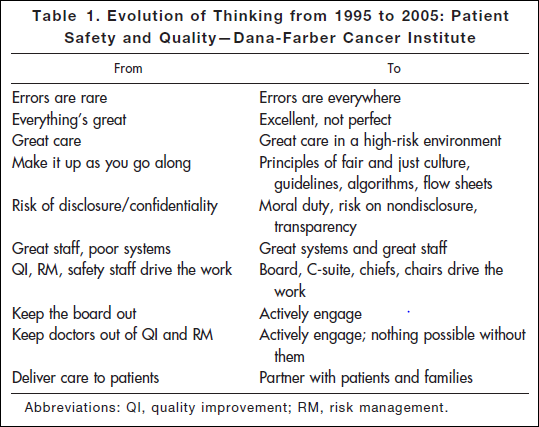

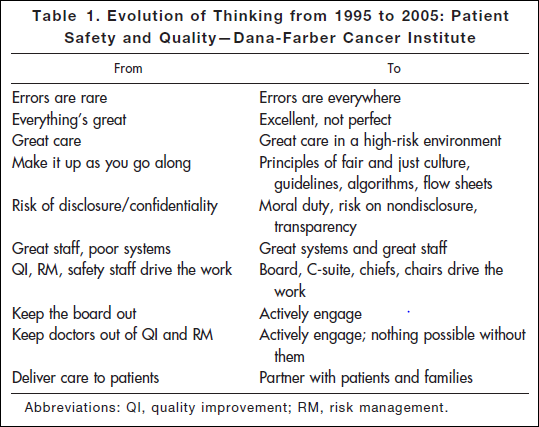

Researching a project today, I came across an article* published in 2006: “Key Learning from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute’s 10-Year Patient Safety Journey.” This table shows the attitude you’ll find in an organization that has realized the challenges of medicine and is dealing with them realistically:

“Errors are everywhere.” “Great care in a high-risk environment.” What kind of attitude is that? It’s accurate.

This work began after the death of Boston Globe health columnist Betsy Lehman. Long-time Bostonians will recall that she was killed in 1994 by an accidental overdose of chemo at Dana-Farber. It shocked us to realize that a savvy patient like her, in one of the best places in the world, could be killed by such an accident. But she was.

Five years later the Institute of Medicine’s report “To Err is Human” documented that such errors are in fact common — 44,000 to 98,000 a year. It hasn’t gotten better: Last November the U.S. Inspector General released new findings that 15,000 Medicare patients are killed in U.S. hospitals every month. That’s one every three minutes. Read more »

*This blog post was originally published at e-Patients.net*

January 6th, 2011 by admin in Research, True Stories

No Comments »

This is a guest post from Dr. Jessie Gruman.

**********

More Can Also Be Less: We Need A More Complete Public Discussion About Comparative Effectiveness Research

When the public turns its attention to medical effectiveness research, a discussion often follows about how this research might restrict access to new medical innovations. But this focus obscures the vital role that effectiveness research will play in evaluating current medical and surgical care.

I am now slogging through chemotherapy for stomach cancer, probably the result of high doses of radiation for Hodgkin lymphoma in the early 1970s, which was the standard treatment until long-term side effects (heart problems, additional cancers) emerged in the late 80s. So I am especially attuned to the need for research that tracks the short and long-term effectiveness — and dangers — of treatments.

Choosing a surgeon this September to remove my tumor shone a bright light for me on the need for research that evaluates current practices. Two of the three surgeons I consulted wanted to follow “standard treatment procedures” and leave a six-centimeter, cancer-free margin around my tumor. This would mean taking my whole stomach out, because of its anatomy and arterial supply.

The third surgeon began our consultation by stating that her aim would be to preserve as much of my stomach as possible because of the difference in quality of life between having even part of one’s stomach versus none. If at all possible, she wanted to spare me life without a stomach.

But what about the six-centimeter margin? “There isn’t really much evidence to support that standard,” she said. “This issue came up and was discussed at a national guidelines meeting earlier in the week. No one seemed to know where it came from. We have a gastric cancer registry at this hospital going back to the mid 1990s and we haven’t seen support for it there, either. A smaller margin is not associated with an increased risk of recurrence.” Read more »

December 31st, 2010 by Toni Brayer, M.D. in Better Health Network, Health Tips

No Comments »

#1 Doctor: Resolve to let patients speak without interruption and describe their symptoms.

Patient: Resolve to focus on the problem I am seeing the doctor about and not come with a list of 10 complaints for a 15-minute office visit.

#2 Doctor: Resolve to keep a pleasant tone of voice when answering night and weekend phone calls from the answering service, patients, or nurses.

Patient: Resolve to get my prescriptions filled during office hours, not forget my medications while traveling, and to use night and weekend phone calls for emergencies only.

#3 Doctor: Resolve to exercise a minimum of four times a week for better health.

Patient: Ditto.

#4 Doctor: Resolve to train my staff and model excellent customer service for patients.

Patient: Resolve to understand that getting an instant referral, prescription, note for jury duty, or letter to my insurance company from my doctor is not my God-given right and I will stop [complaining] if it doesn’t happen the day I request it. Read more »

*This blog post was originally published at EverythingHealth*

December 29th, 2010 by eDocAmerica in Better Health Network, Opinion

No Comments »

Recently, I was involved in a discussion on an email list serve and decided to takes some of my comments on patient autonomy and blog about them. This arose following a debate about whether the term “patient” engendered a sense of passivity and, therefore, whether the term should be dropped in favor of something else, like “client” or something similar.

Having participated in the preparation and dissemination of the white paper on e-patients, I don’t see the need for “factions” or disagreements in the service of advancing Participatory Medicine. As Alan Greene aptly stated: “This is a big tent, with room for all.”

I want all of my patients to be as autonomous as possible. In my view, their autonomy is independent of the doctor-patient relationship that I have with them. They make the choice to enter into, or to activate or deactivate, the relationship with me. They may ignore my input, seek a second opinion, or fire me and seek the care of another physician at any time. They truly are in control in that sense. The only thing I have control over and am responsible for is trying to provide the best advice or consultation I can. Read more »

*This blog post was originally published at eDocAmerica*

The other day I came across this photo of a couple clasping each other in a dramatic tango on the cover of an old medical journal — a special issue from 1999 that was focused entirely on doctor-patient partnership. The tone and subjects of the articles, letters and editorials were identical to those written today on the topic: “It’s time for the paternalism of the relationship between doctors and patients to be transformed into a partnership;” “There are benefits to this change and dangers to maintaining the status quo;” “Some doctors and patients resist the change and some embrace it: Why?”

The other day I came across this photo of a couple clasping each other in a dramatic tango on the cover of an old medical journal — a special issue from 1999 that was focused entirely on doctor-patient partnership. The tone and subjects of the articles, letters and editorials were identical to those written today on the topic: “It’s time for the paternalism of the relationship between doctors and patients to be transformed into a partnership;” “There are benefits to this change and dangers to maintaining the status quo;” “Some doctors and patients resist the change and some embrace it: Why?”