April 28th, 2014 by Dr. Val Jones in Health Tips, Opinion

1 Comment »

As I travel the country providing coverage for inpatient rehab units, I have been struck by the generally high quality of nursing care. Excellent nurses are the glue that holds a hospital unit together. They sound the first alarm when a patient’s health is at risk, they double-check orders and keep an eye out for medical errors. Nurses spend more time with patients than any other hospital staff, and they are therefore in the best position to comment on patient progress and any changes in their condition. An observant nurse nips problems in the bud – and this saves lives.

As I travel the country providing coverage for inpatient rehab units, I have been struck by the generally high quality of nursing care. Excellent nurses are the glue that holds a hospital unit together. They sound the first alarm when a patient’s health is at risk, they double-check orders and keep an eye out for medical errors. Nurses spend more time with patients than any other hospital staff, and they are therefore in the best position to comment on patient progress and any changes in their condition. An observant nurse nips problems in the bud – and this saves lives.

Not only are nurses under-appreciated and under-paid, they are suffering as much as physicians are with new digital documentation requirements. Just as patients are receiving less face time with their physicians, they are also suffering from a reduction in bedside attention from nurses. The need to record data has supplanted our ability to listen to the patient, causing anguish for patients, physicians, and nurses alike.

This being our lot (and with continued “quality improvement” policies that will simply add to the documentation burden) we must find ways to optimize patient care despite inane bureaucratic intrusions. I believe that there are some steps that nurses and doctors can take to improve patient care right now:

1. Minimize “floating.” (Floating is when a nurse is pulled from one part of the hospital to fill in for a gap in coverage in a different unit). It is extremely difficult for nurses to take care of a floor full of patients they’ve never met before. Every time that care of a patient is handed off to someone else (be they MD or RN), there is a risk of forgetting to follow through with a test, procedure, or work up. Simply knowing what “normal” looks like for a given patient can be incredibly important.

For example, left sided weakness is not concerning in a patient with a long-time history of stroke, but what if that is a new finding? If you’ve never met the patient before, you might not realize that the weakness is new and constitutes an emergency. How does a nurse know if a patient’s skin ulcer/rash/pain etc. is better or worse than yesterday? Verbal reports don’t always clarify sufficiently. There are endless advantages to minimizing staff turnover during a patient’s hospital stay. Reducing the total number of nurses who care for individual patients should be a number one priority in hospitals.

2. If you see something, say something. There are a host of reasons why nurses may be hesitant to report patient symptoms. Either they don’t know the patient well and think that the new issue could be “normal” for that patient, or perhaps the physician managing the patient has been unreceptive to previous notifications. However, I am always grateful when a nurse goes out of her way to tell me her concerns, because I generally find that she’s on to something important. My general rule is to over-communicate. If you see something, say something – because that episode of patient anxiety in the middle of the night could be a heart attack. And if I don’t know it’s happening, I can’t fix it.

3. Please don’t diagnose patients without input. I’ve found that nurses generally have excellent instincts about patients, and many times they correctly pinpoint their diagnosis. But other times they can be misled, which can impair their care priorities. For example, I had a patient who was having some difficulty breathing. The nurse told me about it immediately (which was great) but then she proceeded to assume that it was caused by a pulmonary embolism. I explained why I didn’t think this was the case, but she was quite insistent. So much so that when another patient began to have unstable vital signs (and I requested her help with preparing for a rapid response) she stayed with the former patient, believing that his problem was more acute. This doesn’t happen that frequently, but I think it serves as a reminder that physicians and nurses work best as a team when diagnostic conundrums exist.

4. Help me help you. Please do not hesitate to come to me when we need to clean up the EMR orders. If the patient has had blood glucose finger stick checks of about 100 at each of 4 checks every day for 2 weeks, then by golly let’s reduce the checking frequency! If the EMR lists Q4 hour weight checks (because the drop down box landed on “hour” instead of “day” when it was being ordered) I’d be happy to fix it. If a digital order appears out of the ordinary, ask the doctor about it. Maybe it was a mistake? Or maybe there’s a reason for Q4 hour neuro checks that you need to be aware of?

5. Let’s round together. Nurses and physicians should really spend more time talking about patients together. I know that some physicians may be resistant to attending nursing rounds due to time constraints, but I’ve found that there’s no better way to keep a unit humming than to comb through the patient cases carefully one time each day.

This may sound burdensome, but it ends up saving time, heads off problems, and gives nurses a clearer idea of what to look out for. Leaving nurses in the dark about your plan for the patient that day is not helpful – they end up searching through progress notes (for example) to try to guess if the patient is going to radiology or not, and how to schedule their meds around that excursion. Alternately, when it comes time to update your progress note, isn’t it nice to have the latest details on the patient’s condition? Nurses and doctors can save each other a lot of time with a quick, daily debrief.

6. Show me the wounds. Many patients have skin breakdown, rashes, or sores. These are critically important to treat and require careful observation to prevent progression. Doctors want to see wounds at regular intervals, but don’t always take the time to unwrap or turn the patient in order to get a clear view. Alternatively, some MDs simply unwrap/undress wounds at will, leaving the patient’s room without even telling the nurse that they need to be re-wrapped. In some cases, it takes a lot of time to re-dress the complex wound, adding a lot of work to the nurse’s already busy schedule (and offering little benefit, and some degree of discomfort, to the patient).

Nurses, on the other hand, have the opportunity to see wounds more frequently as they provide dressing changes or peri-care at regular intervals. Most nurses and doctors don’t seem to have a good process in place for wound checks. I usually make a deal with nurses that I won’t randomly destroy their dressing changes if they promise to call me to the patient’s bedside when they are in the middle of a scheduled change. This works fairly well, so long as I’m willing/able to drop everything I’m doing for a quick peek.

These are my top suggestions from my most recent travels. I’d be interested in hearing what nurses think about these suggestions, and if they have others for physicians. I’m always eager to improve my patient care, and optimizing my nursing partnerships is a large part of that. 😆

December 16th, 2013 by Dr. Val Jones in Opinion

No Comments »

I am consistently bemused by those who recommend more rigorous or more pervasive standardized testing as the primary means for insuring physician quality. The vast majority of physicians have already passed through a complex gauntlet of multiple choice exams, extended credentialing and certification processes, and lengthy tests of knowledge and skill. And yet, some physicians (to put it bluntly, sorry friends) are very bad at what they do.

I am consistently bemused by those who recommend more rigorous or more pervasive standardized testing as the primary means for insuring physician quality. The vast majority of physicians have already passed through a complex gauntlet of multiple choice exams, extended credentialing and certification processes, and lengthy tests of knowledge and skill. And yet, some physicians (to put it bluntly, sorry friends) are very bad at what they do.

Intellectual intelligence is necessary, but not sufficient, for doctoring. It is emotional intelligence (EI) that is sorely lacking – because it has neither been cultivated, nor selected for, by many training programs. Some educators openly acknowledge the problem, pointing to “extra-curricular activities” as their primary means of distinguishing equally qualified applicants. The disappointing reality is that non-academic performance may be a tie-breaker for students with similar standardized test scores, but raw scores almost always trump any other factor. In the end, we have a physician work force that is highly adept at assimilating and regurgitating facts, but is only accidentally good at human interactions.

Is there hope for change in this arena? I believe that the prognosis is guarded. As our culture becomes more and more digital data-driven, a tsunami of “meaningless use” threatens to drown us all in false quality measures, electronic medical record documentation “quality assurance” requirements, and analysis of trends without comprehension of context or influencing variables outside the scope of the measuring instruments. Lies, damn lies, and statistics. We can’t get enough! And guess who are the biggest proponents of these methods? Why, people who only excel at standardized testing – mostly because their true flaws also lie outside the measuring instruments. Bad doctors (sometimes turned-administrators) themselves are often fueling the onslaught of fruitless quality improvement initiatives.

Dr. Howard Luks, orthopedic surgeon and social media activist, wrote a provocative blog post on the subject of why physicians don’t engage more in social media. He suggests that many avoid it because they lack people-skills in the first place and don’t genuinely enjoy engaging with patients. If you’re a “jerk” in real life, he argues, then what advantage is there to making that more obvious on blogs, Facebook, Twitter, etc.? Better to stay socially quiet.

The interesting thing is that social media might be the most reliable way to discover whether or not your doctor is kind, thoughtful, observant, and detail-oriented. Reading a physician’s thoughts online can help you get to know their true personality and work ethic. In the future it would be nice if medical schools and residency training programs took the time to read applicants’ blogs (for example) instead of crunching their test scores for admission via the path of least resistance. An extra hour of reading up front could save our medical system from a new wave of low EI providers.

As Seth Godin put it, “Uncaring hands are worth avoiding.”

We all recognize the importance of this statement intuitively, but have a hard time quantifying “caring” with standardized tests. That’s why admissions officers and patients alike must use their judgment when selecting doctors. We pay verbal homage to the importance of “clinical judgment” in medicine but in reality are culturally afraid of straying from numbers to support our decision-making.

How will you know a good doctor? You’ll know him [or her obviously] when you see him. And sometimes you can see him best on social media platforms.

***

A few caveats of course:

1. Social Media is a sensitive but not specific test. Meaning, you can probably accurately identify caring doctors from their blogs, etc. but if they don’t have one, it doesn’t mean they aren’t good/caring.

2. It may not matter if you find a great doctor online if they’re not in your limited ACA network. 😕

3. Direct primary care is a potentially excellent way to get connected to exceptional doctors. I am a fan of this movement and have been actively involved in a practice in VA. The practices can reduce costs and enhance quality care, though recent caps on Health Savings Accounts (initiated by the Obama administration) have reduced consumer freedom to spend pre-tax income on direct primary care.

August 28th, 2011 by Michael Kirsch, M.D. in Opinion, Research

No Comments »

Medical malpractice reform is in the news again. Of course, for the medical profession, the medical malpractice system is the wound that simply will not heal. For the plaintiffs bar, in contrast, the medical liability system is the gift that keeps on giving. I have argued that the current system fails on four important fronts.

Medical malpractice reform is in the news again. Of course, for the medical profession, the medical malpractice system is the wound that simply will not heal. For the plaintiffs bar, in contrast, the medical liability system is the gift that keeps on giving. I have argued that the current system fails on four important fronts.

- Efficiency

- Cost

- Fairness

- Quality Improvement

I admit readily that my profession has not been as diligent as it should be in holding ourselves accountable. We have not been forthright in admitting our medical errors, although can you blame us under the current medical liability construct? Read more »

*This blog post was originally published at MD Whistleblower*

February 25th, 2011 by Peggy Polaneczky, M.D. in Opinion, True Stories

No Comments »

A pathologist uses the EMR to find out just a little more about the patient whose cerebro-spinal fluid she has under her microscope — and changes her diagnosis:

This patient had a diagnosis of plasma cell myeloma with recent acute mental status changes. So the lone plasma cell or two I was seeing, among the lymphs and monos, could indicate leptomeningeal spread of the patient’s disease process. I reversed the tech diagnosis to atypical and added a lengthy comment – unfortunately there weren’t enough cells to attempt flow cytometry to assess for clonality of the plasma cells to cinch the diagnosis. But with the information in the EMR I was able to get a more holistic picture on a couple of cells and provide better care for the patient. I cringe to wonder if I might have blown them off as lymphs without my crutch.

The much-hoped-for improvement in quality due to the adoption of EMRs has been elusive to date, so anecdotal experiences like this will be important evidence to consider in judging the impact of the EMR on healthcare outcomes.

Kudos to pathologist Gizabeth Shyner, who writes over at Mothers in Medicine and her own blog, Methodical Madness, for “thinking outside the box.”

*This blog post was originally published at The Blog That Ate Manhattan*

January 21st, 2011 by DavedeBronkart in Health Tips, Opinion

No Comments »

There are several stages in becoming an empowered, engaged, activated patient — a capable, responsible partner in getting good care for yourself, your family, whoever you’re caring for. One ingredient is to know what to expect, so you can tell when things seem right and when they don’t.

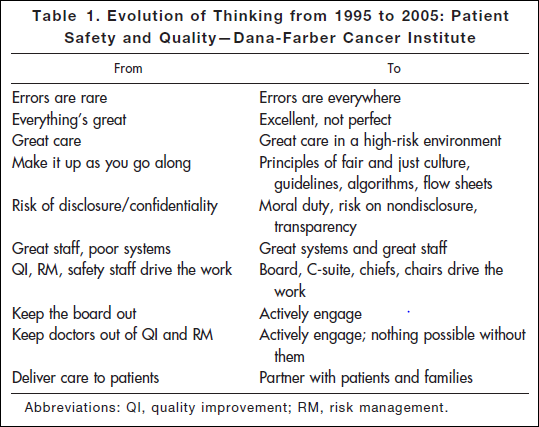

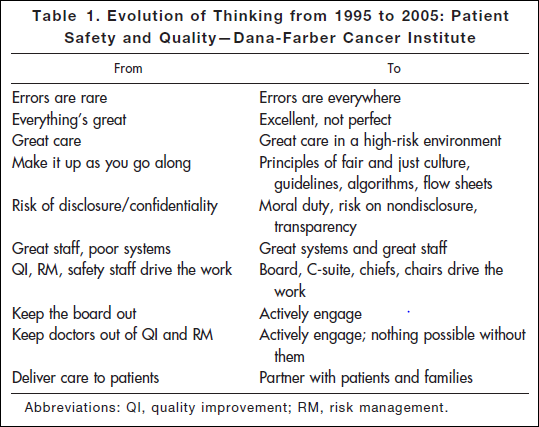

Researching a project today, I came across an article* published in 2006: “Key Learning from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute’s 10-Year Patient Safety Journey.” This table shows the attitude you’ll find in an organization that has realized the challenges of medicine and is dealing with them realistically:

“Errors are everywhere.” “Great care in a high-risk environment.” What kind of attitude is that? It’s accurate.

This work began after the death of Boston Globe health columnist Betsy Lehman. Long-time Bostonians will recall that she was killed in 1994 by an accidental overdose of chemo at Dana-Farber. It shocked us to realize that a savvy patient like her, in one of the best places in the world, could be killed by such an accident. But she was.

Five years later the Institute of Medicine’s report “To Err is Human” documented that such errors are in fact common — 44,000 to 98,000 a year. It hasn’t gotten better: Last November the U.S. Inspector General released new findings that 15,000 Medicare patients are killed in U.S. hospitals every month. That’s one every three minutes. Read more »

*This blog post was originally published at e-Patients.net*

As I travel the country providing coverage for inpatient rehab units, I have been struck by the generally high quality of nursing care. Excellent nurses are the glue that holds a hospital unit together. They sound the first alarm when a patient’s health is at risk, they double-check orders and keep an eye out for medical errors. Nurses spend more time with patients than any other hospital staff, and they are therefore in the best position to comment on patient progress and any changes in their condition. An observant nurse nips problems in the bud – and this saves lives.

As I travel the country providing coverage for inpatient rehab units, I have been struck by the generally high quality of nursing care. Excellent nurses are the glue that holds a hospital unit together. They sound the first alarm when a patient’s health is at risk, they double-check orders and keep an eye out for medical errors. Nurses spend more time with patients than any other hospital staff, and they are therefore in the best position to comment on patient progress and any changes in their condition. An observant nurse nips problems in the bud – and this saves lives.