October 5th, 2010 by Iltifat Husain, M.D. in Better Health Network, News, Research

No Comments »

A team of student and faculty researchers at MIT have developed an open source software system with the goal of improving healthcare access to patients in remote regions.

A team of student and faculty researchers at MIT have developed an open source software system with the goal of improving healthcare access to patients in remote regions.

The software is called Sana and runs on the Android platform. The app allows healthcare workers in remote clinics to send pictures and videos to a database where they can be reviewed by a physician who is then able to provide a preliminary diagnosis via texting.

Sana is different than other collaborative electronic medical sharing efforts because it allows complex medical imaging, such as X-rays and ultrasound images to be uploaded and analyzed.

Since Sana is open source, it can be customized to a specific regions needs and tailored to specific pathologies that need to be studied. Program developers hope this gives healthcare workers a shared sense of responsibility and promotes a level of sustainability. Read more »

*This blog post was originally published at iMedicalApps*

May 13th, 2009 by AlanDappenMD in Primary Care Wednesdays

No Comments »

“OK,” I can hear you say, “Enough about telemedicine. So what if you can prevent two-thirds of office visits by using the phones, or that it’s convenient for the patient and can start them on the road to recovery faster, or that it costs much less money than conducting an office visit, or that malpractice companies have accepted this delivery model.

I can see that you still side with the other non-believers in telemedicine, citing, “Telemedicine is no way to build relationship with patients. Problems abound with telemedicine: It’s too impersonal, patients could easily not be telling you the truth because you lose the “body language and facial expressions,” and it certainly can’t be useful for chronic illness. Maybe it’s good for the simple problems, but this has no place with complex or chronic medical care.”

I do, of course, have some rebuttals for you …

Let’s start with impersonal. In today’s world, we let our friends and family communicate with us constantly through phones and email, and I’ve yet to see how this has destroyed the intimacy of our relationships. So why do Americans anxiously wait up to four days for a doctor’s appointment to get their problem or question resolved and waste at least four hours of a day to get to the office simply to wait for an unpredictable time for a predictable 10-15 minutes of the doctor’s time when so many issues can be resolved remotely by phone? Furthermore, try convincing someone with a urinary tract infection (UTI) or that needs a prescription refill that their long wait, suffering, and run through the primary care funnel were “good for the relationship.” In fact, nothing is more personal that a doctor saying to their patients, “Here is my direct phone number, please call me anytime you need help.” Viewing telemedicine from this perspective determines that the “impersonal” concern is a ruse to protect doctor’s privacy at the expense of their patients.

What about the patient who is not truthful? Does a face-to-face visit make this less likely? In 30 years of work, several patients I know have not always been honest. Many of these people were attractively dressed, well educated and for awhile, fooled me badly. I saw them all face to face too. To this day, I have no idea what to look for when someone is trying to pull the wool over my eyes.

If people are going to hide the truth, they can do it in person just as well as over the phone. When a doctor becomes suspicious about a patient’s truthfulness through a pattern of calls and behaviors, then a scheduled office visit may help. However, forcing office visits based on a blanket rule of thumb of not trusting your patients means there is something fundamentally wrong with the doctor-patient relationship.

Lastly is the idea that chronic disease management isn’t appropriate through phones and email. Really? Let’s say you had diabetes, or hypertension, or high cholesterol, or cancer, or depression, just to name a few. With one of these conditions, you will be in contact with your health professional a lot more than you are now. Not only is your life more complicated, but the doctor wants you to consume 10% of your life waiting to see him in person because it’s good for him. Instead, many of these visits can be conducted easily anytime through phone calls and email.

Here are some examples:

#1. A phone call: “Mr. Doe this is Dr Dappen. I see a calendar reminder that you’re due for labs to check your cholesterol and to make sure the statin drug we put you on is not causing problems. I’ve faxed the order to the lab that is located close to you home, so stop by anytime in the next week and they’ll draw the blood. I should have the results in 24 hours after your visit to the lab, and we can review the report over the phone at that time and decide if we need to make any change.”

#2. An email from a patient: “Dr. Dappen, I’ve been worrying about my blood pressure readings. Over the past 3 weeks, they’ve been running consistently higher. Not sure why and until recently the home readings were doing great. Attached is the spread sheet of readings. Look forward to your input.”

In fact, examples abound of how chronic disease management conducted via phones and email is more efficient, reduces costs, and improves outcomes; I’d invite any Doubting Thomas to visit the American Telemedicine Association for further inquiry. An entire telemedicine industry is gearing up to manage chronic illnesses and most of the time it has nothing to do with patients visiting doctors’ offices.

When all is said and analyzed, the conclusion is really simple as to why the use of telemedicine is not more prevalent: no one wants to pay a doctor the market value for the time it takes to answer a phone and expedite an acute problem or manage a chronic health care problem. No money means no mission. This means no phones, no email. Don’t think about it. See you in the office. Why ruin 2400 years of tradition?

April 29th, 2009 by AlanDappenMD in Primary Care Wednesdays, Uncategorized

3 Comments »

In early 2006, four years into running my current medical practice, doctokr Family Medicine, I got a call from my medical malpractice carrier. Just weeks before I’d received a notice that my malpractice rates could go up by more than 25%. The added news of a pending investigatory audit was chilling. In 25 years of practicing medicine I’d never been audited.

“Is there a complaint, or a law suit against me that I don’t know about?”

“No,” the auditor told me over the phone, “We’ve never seen a medical practice like yours and feel obligated to investigate your process from a medical-legal perspective.”

“Great,” I thought, with a weary sigh. “I’m already battling the insurance model, the status quo of the medical business model, and slow adoption by consumers who are addicted to their $20 co-pay. All I’m trying to do is to breathe life into primary care and get the consumer a much higher quality service for less money than currently subsidized through the insurance model. And now this.”

The time had arrived to add the concerns of the malpractice companies to the list of hurdles to clear if a new vision of a medical care model was ever to catch flight.

I frequently am asked the question “Aren’t you afraid of the malpractice risk?” when I explain my medical practice model, which is based on the doctor answering the phone 24/7, resulting in the patient’s medical problem being solved by the phone more 50% of the time. The simplest counter to this question is to analyze the risk patients incur when the doctor won’t answer the phone. What happens when the doctor is the LAST person to know what’s going on with patients? The answer is obvious. But malpractice companies could have concerns beyond patient safety. Buy-in from the malpractice companies would be critical to the future viability of all telemedicine.

I prepared a summary paper, which included 12 bullet points, explaining how a doctor- patient relationship based on trust , transparency, continuous communications and high quality information systems significantly reduce risk to the person you’re trying to help.

Bullet 1: The industry standard is that 70% of malpractice cases in primary care center on communication barriers. My medical team deploys continuous phone and email communications and 7 days a week- same day office visits when needed between doctor and patient thus significantly reducing these barriers.

.

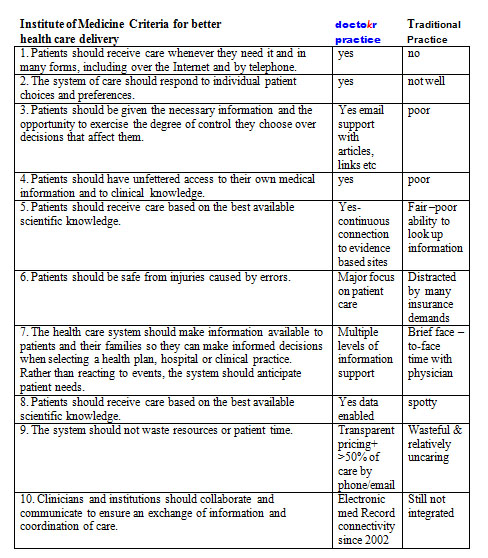

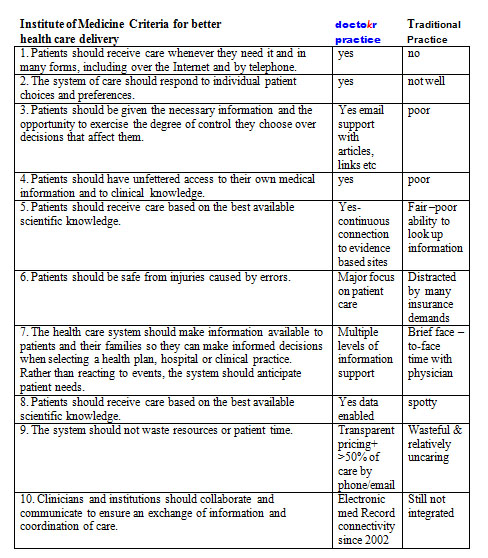

The remaining bullets could be summarized by the conclusions from the Institute of Medicine’s visionary book Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century using a table developed by The American Medical News when they reviewed the book. I carefully plotted our practice standards compared to the traditional business model as it stands today based on this table:

The auditor showed up, spent 4 hours reviewing our practice, electronic medical records, compliance to HIPPA, our intakes, on-line connectivity, procedures, and practice standards. While the auditor reviewed, I sat as unobtrusively as I could, feeling my brow grow damp with perspiration, as I carefully answered her questions. During the auditor’s time, I never moved to sway her to “my way.” I just let the data that I had accumulated from four years of practice do the talking.

Once the auditor left, I waited for two weeks for the results. By the time their letter arrived, I was scared to open it. The news arriving made me jubilant. The medical practice company announced a DECREASE in my premiums because we used telemedicine and EMR to treat patients so fast (often within 10 minutes of someone calling us we have their issue solved without the patient ever having to come in).

I will admit that I felt, and actually still do feel, vindicated by having my malpractice insurer understand fully the value that the type of telemedicine my practice offers to our patients: round-the-clock access to the doctor, speed of diagnosis, and convenience, which all led to healthier patients and lower risk.

Doctors answering the phone all day for their patients, it’s not just lower risk, it’s better health care at a better price. It’s a win-win-win strategy whose day is arriving.

Until next week, I remain yours in primary care,

Alan Dappen, MD

April 15th, 2009 by AlanDappenMD in Primary Care Wednesdays

No Comments »

The most revolutionary tool in primary health care, for almost all out patient care for that matter, is something so common, so mundane, so overlooked that it’s like the nose on your face, you never see it. This tool is not the computer, the internet or a killer software application.

It’s the phone. Why? The answer is equally as simple: The phone allows for 24/7 communication between a doctor and patient who know each other. Likewise, the patient can access the health system with an expert from anywhere and most of the time get what they need.

The American Telemedicine Association (ATA) estimates that 70% of medical problems can be resolved with phones. Almost everyone thinks phone medicine is reserved for an arctic explorer or a poor citizens living in Timbuktu. This assumption ignores how life transforming it would be for every American citizen to pick up a phone, and expect to speak to their doctor anytime from anywhere, at work, on the metro, even on travel, or vacation and expect to resolve their issue instantaneously! No wait, no hassle, no waiting room, no bureaucracy. At least 70% of the time it should be that easy!

Telephone medicine is not to be misconstrued for talking to a stranger. It is not impersonal, nor meant to avoid seeing patients. In reality, it is simply one way of many to get good health care. Sometimes you need a hospital, an emergency room, a specialist, an office visit. However, more than half the time you only need a phone visit, preferably with a doctor or medical practice you know and trust. Even emails are appropriate at times.

That telephones could so easily replace more than 50% of all office visits is so unexamined, so foreign, so shocking, that a predictable series of objections arise:

1. If it was so safe why isn’t it being done already? Of course this begs the reality that our health care system doesn’t pay — or underpays — a doctor to do this. It’s as simple as following the money. Right now the money is in seeing you, so an office visit it must be.

Doctors also answer phones on weekends and night. In fact more than half of the week they are practicing “free telemedicine care,” and that means phone medicine has more real time, more experience in any week than office visit time. It’s just been always deemed “free.” No money means no mission. The doctor, saying, “We’ll schedule you an office visit,” is code for, “Come on in so I can get paid.” That’s a business fact!

2. Isn’t the doctor afraid that he/she’ll miss something? First, office visits miss things all the time. For the sake of not missing something, shouldn’t it mean every problem needs doing a full body scan, complete blood work, and parading every medical problem in front of three separate specialists. If each problem was hospitalized too, maybe that would mean not missing something.

The answer of course, is that to every problem there is a season of reasoning; a triage of appropriateness. Many problems arise where physical exam is irrelevant. If you or the doctor thinks you should be seen, then a face-to-face visit should be arranged but when both people agree what’s going on and that an office visit is not needed, then a phone visit makes sense, which is true over 50% of the time.

3. Isn’t it dangerous for a doctor to answer the phone? To which no one asks the converse question: What’s the experience when the doctor doesn’t answer the phone? If this occurs, then the most knowledgeable person about healthcare, becomes the LAST person to know. This means exposure to the Hippocrates business model of care: long delays, hassled waits, rushed visits. Illness is not a static problem but evolves. The reality of how you feel this minute in front of the doctor often is rendered irrelevant tomorrow when something dramatically changes “Waiting and communicating change” is critical to medical decision making and treatment. Most doctors bring you back in to “see how you’re doing” and make sure they get paid again. It’s not the doctors’ fault, It’s the way the system pays them.

4. Telemedicine, doesn’t that mean higher chances for malpractice? You’ll love the answer to this, but that will need to wait ‘til next week.

Until next time, I remain yours in primary care,

Alan Dappen, MD

April 8th, 2009 by AlanDappenMD in Primary Care Wednesdays

No Comments »

Back in 1983, as a third year medical student, I read a study stating that 80% of medical visits were not needed. After finishing the text, I remember thinking, “Hmm, there aren’t that many hypochondriacs in our office!”

It wasn’t until I had practiced medicine for 20 years that I finally understood this statement for what it really meant: doctors were not helping patients through remote means, instead insisting on seeing patients in the office for all medical issues, even the most routine of issues out of habit, out of fear, out of how to get paid.

In 1996, I set out to prove that allowing established patients to remotely access doctors for care would improve their medical outcomes. I convinced my medical partners to let me conduct an experiment: I would work a few half days on the phones, fielding medical-related calls from our HMO patients. Since HMO plans paid us a flat rate to take care of them, bringing these patients to the office cost us money and offering these patients medical consults by phone instead, for routine issues, would be more cost-effective for us and a lot more convenient for them.

At that time, the front desk fielded over 500 patient calls a day. I sat next to the four receptionists, and the HMO screened patients with straightforward medical problems would be triaged to me. I then would speak to the patient, review their medical history and address their medical issue and get them what they needed. I was able treat 90% of the screened patients I spoke over the phone, while determining that the other 10% needed face-to-face appointments. During a typical 3.5 hour shift, I routinely spoke to 25 patients, and immediately helped 23 of those patients with their medical issues thereby avoiding an office visit.

Unfortunately, the experiment didn’t last long. To the business managers of the practice, we lost $500 in co-pays while I logged half days on the phone, not billing a single dollar for the practice. Where I saw opportunity and a new paradigm, they saw lost income.

Thus, I returned to my routine day, seeing 25 patients a day in person, day after day. But drudgery of this led to deepening despair. So many unnecessary office visits, patients upset with their delays, apologies for running late, and meetings about how to see more patients, see them faster, charge the insurance companies more. In some cases all the delays had led to a complication that could have been avoided with more timely care.

Not undeterred, I discretely planned a study in 1999. For two weeks I collected data on each patient I saw. Recording data on a laptop during each visit, I analyzed three questions: How long did we talk, how long did the exam take, how often did I already know what to do through history alone and not due to findings from the face-to-face exam.

Here are the results: I saw an average of 23 patients a day. The longest office visit was 45 minutes, and the longest physical examination of a complicated patient took 10 minutes. Sixty-six percent of my patient visits had no reason to be in the office, with my diagnosis relying on patient history and not being influenced by my physical exam.

On reflection of the data, the implication of the data awoke me to a new realization. I must step outside the “Matrix” that I had been a part of: a healthcare system that often delayed and even held hostage 2 of 3 patients I saw each day.

But making the decision to step outside this system was not easy: why should I risk my medical career as I knew it, and my financial security to do what is best for my patients and deliver them the quality they care they needed?

It was my wife, who, in 2001, finally convinced me to move on. She wrote a resignation letter to my medical practice, a practice filled with respected friends and colleagues. As I sat pondering the risk I’d confront by handing in the letter, my wife reminded me of a familiar refrain, “Ships are safe at harbor, but that’s not what ships are for.”

And so, in 2002, I founded doctokr Family Medicine, a practice that does step outside the typical paradigm of healthcare. My patients control how and when they are seen by our medical team. At doctokr, all of the patients establish their care through a face-to- face visit at the office. We gather their history, review their records and do an exam. After that, all established patients are free to email or call the doctor directly, 24/7. Over half of patients’ issues are resolved remotely, via phone or email. Our medical team also sees patients if they want to be seen, or if we feel we need to see them 7 days a week.

As a medical practice with 3000 pioneering patients, we sail on empty oceans but with full faith that we will not have done so in vain. Our experience has shown happier and healthier patients, providers with a mission and passion again and pricing that is 50% less than the current system price of healthcare.

For doctors and patients, staying “safe” behind the many unexamined assumptions in health care makes such harbor risky indeed.

Until next week, I remain yours in primary care,

Alan Dappen, MD

A team of student and faculty researchers at MIT have developed an open source software system with the goal of improving healthcare access to patients in remote regions.

A team of student and faculty researchers at MIT have developed an open source software system with the goal of improving healthcare access to patients in remote regions.