Do Elite Academic Centers Provide Better Hospital Care?

A well-to-do patient recently boasted to me about an expensive insurance plan that he had purchased to “guarantee” that he had access to the best healthcare in the United States. Coverage included access to elite academic centers (all the usual suspects) and a private jet service for emergencies. He was utterly confident that his investment was worth the price, but I withheld my own misgivings.

A well-to-do patient recently boasted to me about an expensive insurance plan that he had purchased to “guarantee” that he had access to the best healthcare in the United States. Coverage included access to elite academic centers (all the usual suspects) and a private jet service for emergencies. He was utterly confident that his investment was worth the price, but I withheld my own misgivings.

Hospital quality data suggest that “fancy, brand name hospitals” provide better patient care. But unfortunately there is no guarantee of good outcomes for anyone who sets foot in a hospital. My experience doesn’t exactly square with quality data, and although I realize that there are teams of public and private sector analysts out there furiously rating and ranking hospitals with all manner of outcomes data, I don’t think it means a whole lot for the individual “worried well” patient. Here’s why:

1. Higher overall patient complexity may mean less attention for you. Academic medical centers specialize in caring for those who are often too sick or too complicated to be cared for elsewhere. This means that each patient requires more staff time to address their long list of diseases and conditions. Everything from medication reconciliation to medical testing, to bedside care, requires more time from each provider taking care of them. If you happen to be on a medical floor with complicated neighbors, expect to see less of your doctors and nurses. It’s not fair, but this happens regularly at elite centers, and it’s not in your best interest.

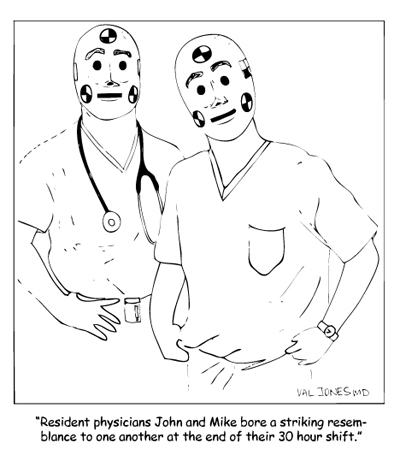

2. Less-experienced physicians may be providing the bulk of your care. Academic teaching hospitals are actively involved in training young doctors, and the least experienced among them will likely be providing the majority of your care (and reporting up to the overseeing physicians). Because of the exhausting complexity of very sick patients, if you are not among the very sickest (or provide a steady stream of diagnostic conundrums requiring the input and expertise from the top experts), your care will be left in the hands of the residents. This doesn’t mean you won’t get good care, but it introduces some degree of risk.

3. You may be exposed to really bad germs. Drug-resistant bacteria are born in places that use big-gun antibiotics. Again, with more challenging cases and infectious diseases in the patient mix, more antibiotics are used and more drug-resistant bacteria develop. Although academic centers make great efforts not to spread infections, it can happen. And if you do get a hospital-acquired infection, it’s probably going to be a bad one.

4. More providers means more opportunity to make EMR-based medical errors. As I’ve argued in recent blog posts, electronic medical records are error prone for a number of reasons. The more people entering data into your record, the more opportunity for mix ups and confusions. Academic medical centers may boast more specialists and a higher staff to patient ratio, but this is not always a good thing. The fewer the number of providers caring for you (especially nurses), the better you are known to them, and therefore the lower the risk of certain mistakes.

5. More tests and procedures aren’t always a good thing. Academic centers have access to a larger breadth of technology, which means that they are more likely to order more tests and procedures. Imaging studies, biopsies, lab tests, and advanced surgical procedures can provide additional information that can change the course of therapy. But they also have the ability to initiate wild goose chases, further testing, unnecessary anxiety, and additional risk (and expense) to the patient. Judicious use of technology is important, but with less experienced physicians on the team, they are more likely to reflexively order a test than to rely on their clinical experience regarding diagnosis and treatment.

6. Many “moving parts” increase your risk for errors, mix ups, and longer wait times. The larger the hospital, the more chances there are for accidental substitutions, name confusion, and test scheduling conflicts. It may seem improbable that these events still occur (Don’t we have bar codes on wrist bands that have solved this problem? You ask.), but if you’re a physician clicking between electronic medical records of patients with the same last name, no bar code will save you. I myself was a patient in the ER of a large elite academic center once, when the security guards confused me with a volatile psychotic patient previously located in the bay that my stretcher was moved into. They almost got the four-point restraints on before I convinced them to re-check my identity with the nurses. Awkward. Also, if you need an MRI or CT scan at a level 1 trauma center, you could be waiting a long time for it as sicker patients bump you from the schedule.

7. Traveling to a center of excellence means post-acute care services will be harder to arrange. If you are recovering from a serious illness or surgery far away from home, case managers will probably have a harder time connecting with services to help you upon discharge. If you need visiting nurses, home-based therapists, durable medical equipment, or follow up care (either with specialists or primary care physicians) all of that will be more challenging to arrange because the case managers don’t have them in their virtual Rolodex. Because of the complexity of the healthcare system, it takes years of effort for good case managers and discharge planners to streamline the process of getting through to the “right person” at each service provider and providing them with the “correct” insurance information and completed forms and paperwork. If they’re lobbying for you out of state or in a far away county, they will probably end up spending a lot of time on hold, or talking to the wrong person. And when you finally arrive home and the visiting nurse doesn’t show up, or you don’t have your walker after all… you will not be happy.

8. You may be stuck with an enormous, post-hospital price tag. Most people nowadays have insurance that covers care at certain “preferred” facilities at a much lower cost to the patient. If you go “outside of network” you may be responsible for a much higher percentage of your care cost than you bargained for. Before you decide to opt for the big brand name academic medical center for your care or procedure, double check with your insurance provider regarding what your part of the cost will be.

If you (or your loved one) are in the unfortunate position of having a rare, life-threatening, or extremely complicated host of diseases and conditions, then you may have no choice but to go to an academic medical center for care. If you’re like my wealthy patient, though, and can afford what you think are insurance upgrades to provide you with access to the “best care available,” you may discover that better care is actually found closer to home.

In an upcoming post, I’ll describe my experience with hospital characteristics that tend to predict a higher quality of care. You may be surprised to find that there isn’t a whole lot of overlap between my personal measures and what we are led to believe are the important ones. 🙂