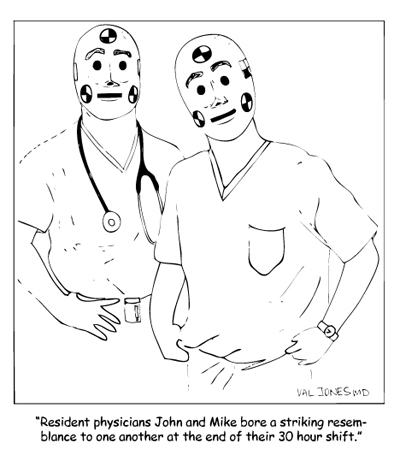

June 14th, 2009 by RamonaBatesMD in Better Health Network

1 Comment »

Recently the WSJ Health Blog posted “Should Doctors Say How Often They’ve Performed a Procedure?” written by Jacob Goldstein. It references another guest post by Adam Wolfberg, M.D — “Test Poses Challenge for OB-GYNs”

Dr. Wolfberg writes:

None of the published studies of CVS pitted seasoned physicians against novices; what patient would agree to be randomly assigned to an inexperienced doctor holding a long needle? But several reports from individual hospitals demonstrate that the miscarriage rate declined over time as the hospital’s staff became more experienced.

These reports point to a dilemma: CVS mavens got that way by practicing, so their present-day patients benefit at the expense of previous patients.

When I first began my solo practice 19 years ago, patients often asked how long I had been in practice. They ask less often these days. I have never failed to answer.

Patients sometimes ask how many times I have done a procedure, but not often. Early in my practice, and sometimes even now, if it is a procedure I feel a bit uneasy with or haven’t done in a while I will bring the subject up without being asked. After all, some procedures you just don’t do every day or even every month. Some diseases you don’t see every month or even every year.

In my mind, many of the procedures I do are built on basic surgical principles. I withdrew my privileges for microvascular procedures more than 10 years ago. I didn’t get enough patients referred to me to feel that my skills were kept sharp. In private practice, unlike at a university, there are no labs to go do practice work in to maintain those rarely used skills. I have no doubt that I could regain them given the chance, but at what cost (financially or complications).

Because I gave up my privileges for microvascular procedures, it means I have limited my repertoire of reconstructive procedures important in hand, breast, and other work. I tell my patients about them. If a breast reconstruction patient wants a free TRAM flap, then she is referred to someone who does it. If she wants to keep me as her surgeon, is there the possibility she is short changing herself on the outcome? I suppose, but I try (TRY) to be upfront and fair to each patient.

The question asked “should doctors say how often they’ve performed a procedure?” may seem an easy one to answer. If asked, yes. If not asked, should it be part of the consent form? I’m not sure it should for most procedures, but for extremely complex ones, maybe.

What if I did 100 of one type of procedure, but my last one was over a year ago? What if I have done 50 of a second procedure that is closely related in skill-set? What if that number is only 15? What if I have never done one and don’t wish to now, but the patient needs the procedure and is not willing to travel to another hospital? Is it okay that I have “informed” them, but they want to take the risk? How do I define that risk for them?

How many of which procedure is enough to become proficient? How often does it need to be done to remain proficient? Who gets to define proficient? Who gets to define the “magic” number of how many is enough to be proficient? Who get to define how often the procedure needs to be done to remain “proficient”?

As Dr Wolfberg noted

What patient would agree to be randomly assigned to an inexperienced doctor holding a long needle?

So how will these questions be answered?

*This blog post was originally published at Suture for a Living*

June 4th, 2009 by RamonaBatesMD in Better Health Network

No Comments »

My mother died last Tuesday. She had her coronary bypass surgery just one week before that day. It was during her CABG that she had her strokes. Yes, strokes, plural. She was one of those 1.5% who suffer macroemboli cerebral strokes during coronary bypass surgery.

I went looking for information on it earlier this week. I went through my training without ever seeing this complication. Like everyone, I never thought my family would be the one. I think it is better to go to surgery, NOT thinking you will be the “statistic” as far as complications go. Anyone having surgery, SHOULD go into it feeling hopeful and thinking everything will go perfectly.

The article referenced below is a good review of this complication – stroke during coronary bypass surgery. The study is a retrospective review of 6682 consecutive coronary bypass patients who only had the CABG procedure and not other simultaneous procedures, such as carotid endarterectomy.

They list the possible sources of the emboli as the ascending aorta, carotid arteries, intracerebral arteries, or intracardiac cavities. They state that they believe the most likely source is the ascending aorta, for the following reasons:

First, the ascending aorta is the site of surgical manipulations during CABG, whereas mechanical contact is not made with the other potential sources of emboli. Embolization of atherosclerotic debris is most likely to occur during aortic cannulation/decannulation, cross-clamp application/removal, and construction of proximal anastomoses. However, embolization of atherosclerotic debris may also occur when the aorta is not being surgically manipulated, due to the ‘sandblast’ effect of CPB.

Second, the majority of our independent predictors of stroke – elderly age, left ventricular dysfunction, previous stroke/TIA, diabetes, and peripheral vascular disease – are strongly associated with atherosclerosis of the ascending aorta.

Third, our chart review suggested that the most common probable cause of stroke was atherosclerotic emboli from the ascending aorta. Palpable lesions in the ascending aorta were noted in a large proportion of stroke patients.

The fourth reason we believe the ascending aorta is the likely source of macroemboli is because of ancillary autopsy data. …….

Note the second reason given above – the independent predictors of stroke. My mother was over 74 yr so fell into the elderly age risk factor group. She was also a type 2 diabetic. She was noted to have a small abdominal aneurysm and some renal artery stenosis on the angiogram (an accidental pickup). So she had three of the four independent risk factors.

REFERENCES

Stroke during coronary bypass surgery: principal role of cerebral macroemboli; Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2001;19:627-632; Michael A. Borger, Joan Ivanov, Richard D. Weisel, Vivek Rao, Charles M. Peniston

*This blog post was originally published at Suture for a Living*

May 26th, 2009 by Medgadget in Better Health Network

2 Comments »

“.. imagine it is the tool with which you are about to remove a man’s limb. This is a dark, sombre instrument, with serious purpose.”

We don’t often unbox things here at Medgadget. For whatever reason, Phillips and GE keep forgetting to mail us their latest CT scanners for review. And Intuitive Surgical, where’s our da Vinci? We need something to make our morning lattes. That being said, recently we got our hands on a wonderfully preserved, rare 1800s surgical kit, made by the famous pre-civil war surgical equipment manufacturer Henry Schively out of Philadelphia, PA. We thought we’d use this opportunity to reminisce on surgery of the past, you know, before ether was given a try, and when surgeons could operate in formal attire. To help us on our voyage through the kit, Medgadget has enlisted our friend Dr. Laurie Slater, whose website Phisick showcases a formidable collection of medical and surgical antiques. Being more knowledgeable on such matters than us, he has kindly offered to act as our guide. From the confines of this post / interview, we’ll explore the surgical kit, touch on surgery in the 1800s, and get you thinking about the days when you’d probably dress like these gentlemen.

So let’s get started. Hinge opening… Now.

Dr. Slater, thank you for kindly serving as our guide through this kit.

You are very welcome. I’m delighted to be able to get a first hand look at this lovely surgical set, so thanks for asking me.

Before we dig into our kit, tell us a bit about why you started collecting medical antiques? What prompted you to start Phisick and where did the word ‘Phisick’ come from?

What I first thought would be a passing interest was not. I come from an era of medicine where much of the equipment tends to be plastic and throw-away. The first time I set eyes on some of the older surgical instruments, I was bowled over by the incredible workmanship and the painstaking effort which someone had lavished on them. I remember thinking that whoever had constructed them a) knew what they were doing and b) was in no hurry. They were of the highest quality, made from the finest materials, with a mastery of design and engineering which, I fancied, would have challenged the legendary skill of the elfin silversmiths of Lothlorien. They had function, obviously, but also form.

Take for example the capital saw (the large one) in your set. The handle is made from dark black smooth ebony which is a durable hardwood, polished and oiled over many hours to a smooth waterproof finish. The curve of the handle is simple, but with a design reminiscent of something from the animal kingdom. Well weighted in the hand; the inner curve fitting the surgeons grip and the upper ‘fin’ and lower ‘fish tail’ anchoring the palm to the handle. This, along with the crosshatching will prevent any slippage when the teeth of the the cold polished steel meet with bone.

Stop for a moment and have another look, but this time imagine that this instrument is about to saw through your own leg without anaesthetic. Or look at it from the surgeon’s point of view and imagine it is the tool with which you are about to remove a man’s limb. This is a dark, sombre instrument, with serious purpose.

An appreciation of these instruments and the men who designed and constructed them has helped me see medicine and history in a different light, and an altogether more vibrant context.

About “Phisick”… The word was commonplace in the 1500s and synonymous with our current day “medicine.” Spelling back then was fairly relaxed and no-one much worried about interchanging a “y” for an “i”. You could ‘take phisick’ by swallowing a pill, or doctors could ‘practise phisick’ by trying to cure their patients. So this was the name I chose for a website which celebrates the beautiful, breathtaking, sometimes life-giving tools invented by the pioneers of medicine and surgery.

We’re fortunate to know a bit of history behind this set. It belonged to a Dr. Geo L. Shearer (an ancient relative of one of your editors), who practiced medicine in Dillsburg, Pennsylvania from 1825 to 1878. Were such personal surgical kits normal possession of doctors in that era?

We’re fortunate to know a bit of history behind this set. It belonged to a Dr. Geo L. Shearer (an ancient relative of one of your editors), who practiced medicine in Dillsburg, Pennsylvania from 1825 to 1878. Were such personal surgical kits normal possession of doctors in that era?

Knowing who the owner really brings this piece to life. I found a great account of Dr. George L Shearer and which included his role in the history of Dillsburg. The census in 2000 listed the population of Dillsburg at 2063, but when he first started there this figure was closer to 600. He was clearly a pillar of his local society – Chief Burgess of the borough, School Director, member of the Town Council and active in securing the Borough Charter, the State Road from Dillsburg to York, and the railroad. But for the people living there he would have been first and foremost their doctor. The author of this account of Dillsburg describes his “passing from time into eternity” in 1878 and he is also mentioned in his son’s obituary as “The beloved physician” so he was clearly held in both warm and high esteem.

The surgical set you have here in style and configuration is no later than 1840 and predates the civil war by over 20 years which raises the possibility that as the owner, he might have had some prior surgical training. However, the amount of use it would have had at the hands of a local doctor in a small town would have been pretty limited and it seems more likely that if this set had seen much use that it would have done so during the years of the Civil War. During the Gettysburg Campaign, Dillsburg was twice invaded by Confederate cavalry at which time Dr Shearer would have been 61. If he had performed surgery at this time he would have done so in one of two roles, either as a militia surgeon, or a contracted private surgeon. At the start of the war the army forces on either side had their own army surgeons, those of the Union forces numbered 113, of which 24 joined the Confederates. Such were the terrible casualties in an engagement managed by pre-war strategies designed to suit professional soldiers, but acted out by massive numbers of poorly trained civilian recruits, that by the end of the war over 15,000 surgeons had been required to serve in the army forces of either side. Bollet, a civil war historian writes about this:

“During the first year of the war, and especially during the Peninsula Campaign in 1862, army surgeons performed all operations. Soon the overwhelming numbers of battle wounded forced the army to contract civilian surgeons to perform operations in the field alongside their army counterparts. Their ability ranged from poor to excellent.”

In fact, because of controversy over the staggering number of casualties, strict rules were put in place to ensure that only experienced surgeons could operate and one figure suggests that only one in fifteen doctors performed amputation surgery. If Dr Shearer had had such a role he might have used this set to treat both wounded local conscripts from his home town (the number varied in the account I have read but was circa 30 of which 8 died) or soldiers with war wounds (who would have numbered considerably more). In fact, neither George L. Shearer nor his son, James M. Shearer are listed in the A.M.A. Deceased Physicians database. This in itself is not uncommon. Nor is he listed as a surgeon or asst. surgeon in the Roster of Regimental Surgeons for the Union Army, (but he would not have been of course unless he had actively joined the Union Army). Interestingly his son James M. Shearer is listed in the Roster as an assistant surgeon from Dillsburgh, Pa., who served until Aug. 1863. with the Pennsylvania 12th Reserves Infantry, (41st. Volunteers.) Nor is George L mentioned in the Medical and Surgical History of the War of Rebellion. So without any corroborative evidence that he was a surgeon in the Civil war it is not possible to say that this is a civil war surgical set, but the story as it has unfolded so far raises some fascinating possibilities.

In general, how would surgery be done in the 1800s? Would doctors ever operate on house calls? Any sort of anesthetics?

Dr Shearer practiced medicine in Dillsburg and to the six hundred residents of this backwater town in Pennsylvania he would also have been their physician, surgeon, gynaecologist, obstetrician and paediatrician. This heavy set contains instruments used for major surgery such as amputation or craniotomy. In practice, in a town of Dillsburg’s size, outside of war, either of these operations would have been very rare and I doubt it would have seen a great deal of use in this context. It certainly would not have been carried with him on any regular basis. Most likely he would have had another medical bag or physicians leather pocket case in which the more common instruments in daily use were contained and which he would have taken on his house calls. The sort of surgery he might have undertaken would have been suturing of wounds, the drainage of an abscess or possibly the treatment of a superficial flesh would from a bullet (likewise not a common injury in peacetime). He might have used the smaller knives, forceps and needles in the set for this. Local anaesthetic was not invented until the 1880s and none of these procedures wound would have merited ether or chloroform and so would have been done without anaesthetic.

With regards to surgery, the turning point in the 1800s was circa 1846, with the introduction of anaesthesia. Prior to this time the use of an orderly to hold the patient down and alcohol or opium was a poor substitute, and meant that only absolutely major surgery could be undertaken. By far the most common operation was amputation, but also craniotomy (drilling holes in heads – which I will talk about later) and also the removal of bladder stones. The imperative in any case where the patient was conscious would have been to perform surgery as quickly as possible and the earlier surgeons prided themselves in the speed at which they could operate, some claiming to be able to remove a leg in under one minute!

After the introduction of anaesthesia there was a rising tide of surgical procedures. Most of them however would have been done in the civilian hospitals. In Massachusetts Hospital there were a mere 39 operations carried out in the 10 years prior to 1846 and 189 operations (60% of them were amputations) in the 10 years post. It was not until the turn of the century however with the introduction of antisepsis and asepsis that the volume increased significantly by which time in Massachusetts they were averaging 2,427 operations each year.

During the civil war it was estimated that as many as 60,000 amputations were performed on both sides. Because of horrific casualties of war and their appalling prognosis, the surgeons of the time were given pretty bad press and held in poor esteem by the public. Rumours abounded that amputations were performed needlessly, even though this was almost certainly not the case. Surgeons were also accused of performing amputation without anaesthetic. With the notable exception in 1862 of 254 casualties at the battle of Luka, this was not true either, but the reason such accusations exist have explanation. Most of the amputations were performed outside because sunlight afforded by far the best illumination and so many procedures were done in public view of “passers by.” The anaesthetic would be applied by placing a cloth over the nose and face which had been soaked in either ether, or chloroform or a mixture of the two. As soon as the patient passed out the cloth was removed and this would have afforded only a relatively light anaesthetic. (And probably just as well because had it been held in place longer, fewer patients may have woken up). However, the light anaesthetic meant that the patients would tend to thrash around during the procedure even whilst unconscious. It seems likely that the observation of such movements in a public forum would lead to the assumption of an untrained eye, that the patient was still awake.

Given that these kits were used many, many times, how common were infections as a result of surgical procedures in the 1800s?

Many of the surgical procedures done in the civil war were complicated by infection as they were done without the knowledge of the role that bacteria played or the benefits of antisepsis and asepsis. Hospitals of the time were characterised by the stench of the ubiquitous pus and infection. The overcrowded and unhygienic conditions made the situation worse. Thick creamy pus from staphylococcal infection was referred to as “laudable pus” because it tended to be local in nature. The more serious infection from streptococcal infection produced a clear watery or bloodstained discharge and was called malignant because it caused septicaemia and death, hospital gangrene and osteomyelitis. The latter was a chronic infection in bone which was a complication of the almost inevitable infections which followed broken bones exposed to the air. The presence of osteomyelitis was a common indication for amputation.

This particular kit was made by Henry Schively. Since we’re a medical technology blog, would you mind briefly telling us about the medical instruments manufactured in that era?

In the late 18th century most American surgeons were buying their instruments abroad, or from agents who had imported them from England. Henry Schively (1761 – 1811) is described in Edmonson’s book on American surgical instruments as ‘the Premier Philadelphia surgical instrument maker of the era of heroic surgery’ which was the period from 1774 to 1840. He along with a number of other local artisans (there were 50 master smiths registered in the thriving city of Philadelphia, 10 of whom were listed as “instrument makers”) contributed to Philadelphia becoming the centre of the American instrument trade. Supporting this development was the fact that Philadelphia and the surrounding regions had also become the leading American medical centre of the time, boasting the very first public anatomy lectures and dissections, as well as the first medical school, the university of Pennsylvania. The first surgical chair of this medical school was held by Philip Physick, the “father” of American surgery. Relatively few of these early master craftsmen managed to sustain successful businesses but Henry Schively and John Rohr were among the better known. Schively was famous for inventing the Bowie knife, although it was his focus on making surgical instruments which marked him out and he was approached by many surgeons, Physick amongst them to construct and refine instruments which they had invented. Schively and the family business later carried on by his son beyond 1850 was acknowledged in its time as one of the finest surgical instrument makers in America.

Here’s an overview of the kit showing all of the tools inside. Do you think this was a common, general surgical kit, or do you think it might have been for more specialized procedures?

The set contains the basic surgical tools which would have been needed to perform emergency surgery by way of amputation and this is not an uncommon configuration. The essential tools for this would usually comprise of a Liston knife or knives which had long straight razor sharp blades polished steel blades for cutting through the muscle. A capital saw (the large one) was for sawing through weight bearing bones. The forceps and smaller knives would have been used for trimming the muscle and skin in such a way as to produce flap. The needles were used to sew the flap of skin and muscle in place over the bone stump. There would also have been a tourniquet for applying pressure around the limb to temporarily cutt off the blood supply.

In addition to these surgical tools the set also contains two hand trephines and other instruments used for trepanation. These would often come separately in their own case and so this set represents a “compendium” if you like. Other examples of sets which combined instruments for different purposes were carried on board ships. These were grand compendia with comprehensive collections of tools to manage all eventualities, including general surgical, orthopaedic, urological, ophthalmological and dental instruments.

This is the trepanning set within the kit. Would you mind briefly describing why a doctor would perform trepanning and how he would do the procedure?

Trepanation is the procedure of drilling a hole in the skull. The two main reasons for doing this would be to drain a collection of blood which had accumulated between the skull and the surface of the brain, or to elevate a depressed bone fracture. The former, often referred to as a subdural haematoma would raise the pressure within the skull and cause brain damage, and in a depressed fracture it was the bone of the skull pushing on the brain (like a collapsed ping-pong ball) which would damage the brain or causes it to swell. When done correctly for the right indications trepanation is a relatively simple procedure which is life saving. This set contains two drills with different sized crowns (“drill bits”), either of which can be attached with a screw to the horizontal crosshatched ebony handle. This forms a drill which is used in a similar way to a cork screw. A flap of scalp would first have been raised to clear the area of the skull to be tapped. In order to anchor the circular drill and prevent slippage a central spike is moved forward and fixed in place to start the drilling (see here). The drill is turned through the cranium until a disk of bone can be removed. This may have been pried out with a lever like ‘elevator’ and the edges of bone trimmed with a sharp knife or ‘lenticular’ and filed down with a ‘raspatory’. The instrument on the top right hand side of the case would probably have been used as a combination of an elevator and raspatory. Sometimes one hole would be enough to drain a collection of blood. Other times a larger plate of skull would need to be removed and this was done by drilling three or more holes and passing a small abrasive wire (a Gigli saw) between two holes at a time to saw through the intersection.

Tell us, if you could, about the the lancet and what they’d be used for? Why was a scalpel or normal knife not sufficient to let blood?

Tell us, if you could, about the the lancet and what they’d be used for? Why was a scalpel or normal knife not sufficient to let blood?

Patients were frequently bled by their physicians in the 19th century and this was considered a panacea for numerous complaints ranging from headaches to gout. It was almost certainly ineffective in 99.9% of them. One such phlebotomy instrument used was the “spring lancet”. The name is largely self explanatory. The device is primed by pulling the black lever which also moves the blade upwards and holds it in position under tension. The lower edge of the instrument is held over the area to be bled and it is fired by pressing the arm on the side which released the blade at speed into the flesh. The ensuing blood was usually collected in cups applied to the skin (see here). I doubt that this spring lancet came with the set originally but would have been a later addition. It is the sort of instrument Dr Shearer might well have carried on his person or in his medical bag. Physicians also used small knives and thumb lancets to do the bleeding but because the spring lancet was able to pass the blade through the skin more quickly, they were less painful. Later automatic devices called scarificators worked on similar principles but primed multiple blades at a time (see here).

The above vertebrae was found in the kit. Any idea why a surgeon might keep that around!?

This is a human cervical vertebra (from the neck). The central body has been drilled and so it almost certainly once belonged to an anatomical model skeleton. The reason it has found its way into this set is not obvious. The container in which it sits, along with the spring lancet is where the tourniquet for this set would have gone.

What do you think this little brush might have been used for?

This is a brush which would have been used to brush away the small pieces of skull bone which accumulated around the drill bit during trepanation. It is probably made from bone although it could be ivory. Although most of the pieces in the set are made from ebony it is possible that this was original as a number of items in the set do combine the two.

What about these saws? How do you think they might have been used? Amputations?

The top saw is called a Hey saw after William Hey an English surgeon (1736-1819). It is used to perform craniotomies, but instead of using a trepan, Hey removed a plate of bone by sawing linear intersecting lines through the skull. The middle saw we have talked about is called a capital saw and this is the large saw which would have been used in leg amputations to saw through the femur or tibia. The bottom one is called a metacarpal saw and would have been used to cut smaller bones in the forearm or hand or finger bones.

Anything else in the kit or about the kit that you’d like to comment on?

Just to reiterate that this is a superb very early surgical set made by one of the most famous American instrument makers and I am delighted to have had the opportunity to look at it and explore the history with you. American and civil war surgical instruments are not my specific area of expertise and so this exercise has been very educational and enjoyable one for me.

Thank you so much for helping us out! If our readers what to learn more about medical antiques, do you have any recommendations for books, or other resources (besides Phisick of course) that they might want to check out?

There are a number of good books on antique medical and surgical instruments which include:

Antique Medical Instruments by Elisabeth Bennion

American Surgical Instruments by James Edmonson

Medicine: Perspectives in History and Art by Robert Greenspan

For those with a more specific interest in Civil War surgical instruments I would recommend a trip to Michael Echols’ web site which reflects his wealth of knowledge on this subject. I particularly want to thank Michael for the help he graciously offered in researching this set.

I would also recommend reading Bollet’s illuminating article “The truth about Civil War surgery“.

Lastly your readers may be interested in browsing the links page at Phisick.com where they can find a number of sites related to medical antiques and the history of medicine.

*This blog post was originally published at Medgadget*

We’re fortunate to know a bit of history behind this set. It belonged to a Dr. Geo L. Shearer (an ancient relative of one of your editors), who practiced medicine in Dillsburg, Pennsylvania from 1825 to 1878. Were such personal surgical kits normal possession of doctors in that era?

We’re fortunate to know a bit of history behind this set. It belonged to a Dr. Geo L. Shearer (an ancient relative of one of your editors), who practiced medicine in Dillsburg, Pennsylvania from 1825 to 1878. Were such personal surgical kits normal possession of doctors in that era?

Tell us, if you could, about the the lancet and what they’d be used for? Why was a scalpel or normal knife not sufficient to let blood?

Tell us, if you could, about the the lancet and what they’d be used for? Why was a scalpel or normal knife not sufficient to let blood?