January 21st, 2015 by Dr. Val Jones in Opinion, True Stories

1 Comment »

In my last blog post I discussed how harmful physician “thought leaders” can be when they are dismissive of the value of other specialists’ care. I must have touched a nerve, because a passionate discussion followed in the comments section. It seems that physicians (who spend most of their time involved in clinical work) are growing tired of the leadership decisions of those who engage in little to no patient care. Clinicians urge lawmakers to turn to practicing physicians for counsel, because those who are out of touch with patients lack real credibility as advisers.

In my last blog post I discussed how harmful physician “thought leaders” can be when they are dismissive of the value of other specialists’ care. I must have touched a nerve, because a passionate discussion followed in the comments section. It seems that physicians (who spend most of their time involved in clinical work) are growing tired of the leadership decisions of those who engage in little to no patient care. Clinicians urge lawmakers to turn to practicing physicians for counsel, because those who are out of touch with patients lack real credibility as advisers.

Interestingly, the credibility question was raised in a different light when I was recently contacted by a prestigious medical organization that was seeking expansion of its board membership. I presumed that this was a personal invitation to join the cause, but soon realized that the caller wanted to use my influence to locate “more credible” candidates with academic gravitas.

When I asked what sort of candidate they wanted my help to find, the response was:

“A physician with an academic appointment at a name brand medical school. Someone who isn’t crazy – you know, they have to be respected by their peers. Someone at Harvard or Columbia would be great. You must know someone from your training program at least.”

While I appreciated the honesty, I began thinking about the age-old “town versus gown” hostilities inspired by academic elitism. In medicine, as with many other professions, it is more prestigious to hold an academic position than to serve in a rural community. But why do we insist on equating credibility with academics?

Another facet of credibility lies in physicians’ tendencies to admire only those at the top of their specific specialty. Dr. Lucy Hornstein described this phenomenon in her powerful essay on “How To Drive Doctors To Suicide:”

“Practice that condescending look and use it at hospital staff events. Make it a point to ignore newcomers. Concentrate on talking just with your friends and laughing at inside jokes, especially when others are around. Don’t return their calls, and don’t take their calls if you can possibly help it. If you accidentally wind up on the phone with the patient’s primary physician, just tell them you’ve got it all under control, and that he (and the patient) are so lucky you got involved when you did.”

A reader notes:

“And perhaps those of us who do see patients should get some self esteem and stop fawning all over [physician thought leaders] at conferences like needy interns.”

And finally, there seems to be an unspoken pecking order among physicians regarding the relative prestige of various specialties. How this order came about must be fairly complicated, as dermatology and neurosurgery seem to by vying for top spots these days. I find the juxtaposition almost amusing. Nevertheless, it’s common to find physicians in the more popular specialties looking down upon the worker bees (e.g. hospitalists and family physicians) and oddballs (e.g. physiatrists and pathologists).

While I try very hard not to take offense at my peers’ dismissiveness of my career’s value, it becomes much more concerning when funding follows prejudicial lines in the medical hierarchy. As a sympathetic family physician writes:

“I have observed the inequitable distribution of resources from the less glamorous to the sexy sub specialties despite obvious patient needs. Unfortunately, the administridiots who usually lack any medical training, opt to place resources where they are most likely to attract headlines.”

Yes, caring for the disabled (PM&R) is “less glamorous” than wielding a colonoscope (GI) (again, not sure who made that decision?) but it should not be less credible, or become a target for budget cuts simply because people aren’t informed about how rehab works.

It is time to stop specialty prejudice and honor those who demonstrate passion for patients, regardless of which patient population, body part, or organ system they serve. Excellent patient care may be provided by academics, generalists, or specialists, by those who practice in rural areas or in urban centers. The best “thought leaders” are those who bring unity and an attitude of peer respect to the medical profession. With more of them, we may yet save ourselves from mutually assured destruction.

January 13th, 2015 by Dr. Val Jones in Health Policy, Opinion

7 Comments »

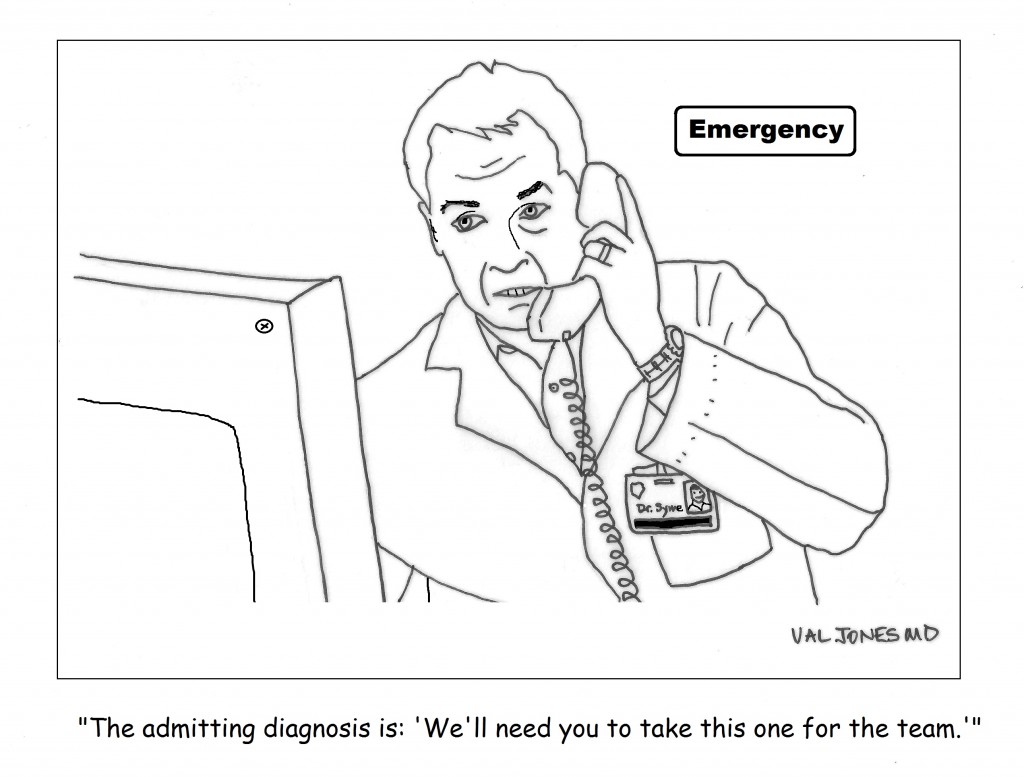

It’s no secret that medicine has become a highly specialized business. While generalists used to be in charge of most patient care 50 years ago, we have now splintered into extraordinarily granular specialties. Each organ system has its own specialty (e.g. gastroenterology, cardiology), and now parts of systems have their own experts (hepatologists, cardiac electrophysiologists) Even ophthalmologists have subspecialized into groups based on the part of the eye that they treat (retina specialists, neuro-ophthalmologists)!

It’s no secret that medicine has become a highly specialized business. While generalists used to be in charge of most patient care 50 years ago, we have now splintered into extraordinarily granular specialties. Each organ system has its own specialty (e.g. gastroenterology, cardiology), and now parts of systems have their own experts (hepatologists, cardiac electrophysiologists) Even ophthalmologists have subspecialized into groups based on the part of the eye that they treat (retina specialists, neuro-ophthalmologists)!

This all comes as a response to the exponential increase in information and technology, making it impossible to truly master the diagnosis and treatment of all diseases and conditions. A narrowed scope allows for deeper expertise. But unfortunately, some of us forget to pull back from the minutiae to respect and appreciate what our peers are doing.

This became crystal clear to me when I read an interview with a cardiologist on the NPR blog. Dr. Eric Topol was making some enthusiastically sweeping statements about how technology would allow most medical care to take place in patient’s homes. He says,

“The hospital is an edifice we don’t need except for intensive care units and the operating room. [Everything else] can be done more safely, more conveniently, more economically in the patient’s bedroom.”

So with a casual wave of the hand, this physician thought leader has described a world without my specialty (Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation) – and all the good that we do to help patients who are devastated by sudden illness and trauma. I can’t imagine a patient with a high level spinal cord injury being sent from the ER to his bedroom to enjoy all the wonderful smartphone apps “…you can get for $35 now from China.” No, he needs ventilator care and weaning, careful monitoring for life-threatening autonomic dysreflexia, skin breakdown, bowel and bladder management, psychological treatment, and training in the use of all manner of assistive devices, including electronic wheelchairs adapted for movement with a sip and puff drive.

I’m sure that Dr. Topol would blush if he were questioned more closely about his statement regarding the lack of need for hospital-based care outside of the OR, ER and ICU. Surely he didn’t mean to say that inpatient rehab could be accomplished in a patient’s bedroom. That people could simply learn how to walk and talk again after a devastating stroke with the aid of a $35 smartphone?

But the problem is that policy wonks listen to statements like his and adopt the same attitude. It informs their approach to budget cuts and makes it ten times harder for rehab physicians to protect their facilities from financial ruin when the prevailing perception is that they’re a waste of resources because they’re not an ICU. Time and again research has shown that aggressive inpatient rehab programs can reduce hospital readmission rates, decrease the burden of care, improve functional independence and long term quality of life. But that evidence isn’t heeded because perception is nine tenths of reality, and CMS continues to add onerous admissions restrictions and layers of justification documentation for the purpose of decreasing its spend on inpatient rehab, regardless of patient benefit or long term cost savings.

Physician specialists operate in silos. Many are as far removed from the day-to-day work of their peers as are the policy wonks who decide the fate of specialty practices. Physicians who have an influential voice in healthcare must take that honor seriously, and stop causing friendly fire casualties. Because in this day and age of social media where hard news has given way to a cult of personality, an offhanded statement can color the opinion of those who hold the legislative pen. I certainly hope that cuts in hospital budgets will not land me in my bedroom one day, struggling to move and breathe without the hands-on care of hospitalists, nurses, therapists, and physiatrists – but with a very nice, insurance-provided Chinese smartphone.

January 5th, 2015 by Dr. Val Jones in Health Tips, Research

No Comments »

Wear and tear on the knee joints creates pain for up to 40% of Americans over age 45. There are plenty of over-the-counter (OTC) and prescription (Rx) osteoarthritis treatments available, but how effective are they relative to one another? A new meta-analysis published by the Annals of Internal Medicine may shed some light on this important question. After 3 months of the following treatments, here is how they compared to one another in terms of power to reduce pain, starting with strongest first:

Wear and tear on the knee joints creates pain for up to 40% of Americans over age 45. There are plenty of over-the-counter (OTC) and prescription (Rx) osteoarthritis treatments available, but how effective are they relative to one another? A new meta-analysis published by the Annals of Internal Medicine may shed some light on this important question. After 3 months of the following treatments, here is how they compared to one another in terms of power to reduce pain, starting with strongest first:

#1. Knee injection with gel (Rx hyaluronic acid)

#2. Knee injection with steroid (Rx corticosteroid)

#3. Diclofenac (Voltaren – Rx oral NSAID)

#4. Ibuprofen (Motrin – OTC oral NSAID)

#5. Naproxen (Alleve – OTC oral NSAID)

#6. Celecoxib (Celebrex – Rx NSAID)

#7. Knee injection with saline solution (placebo injection)

#8. Acetaminophen (Tylenol – OTC Synthetic nonopiate derivative of p-aminophenol)

#9. Oral placebo (Sugar Pill)

I found this rank order list interesting for a few reasons. First of all, acetaminophen and celecoxib appear to be less effective than I had believed. Second, placebos may be demonstrably more effective the more invasive they are (injecting saline into the knee works better than acetaminophen, and significantly better than sugar pills). Third, injection of a cushion gel fluid is surprisingly effective, especially since its mechanism of action has little to do with direct reduction of inflammation (the cornerstone of most arthritis therapies). Perhaps mechanical treatments for pain have been underutilized? And finally, first line therapy with acetaminophen is not clinically superior to placebo.

There are several caveats to this information, of course. First of all, arthritis pain treatments must be customized to the individual and their unique tolerances and risk profiles. Mild pain need not be treated with medicines that carry higher risks (such as joint infection or gastrointestinal bleeding), and advanced arthritis sufferers may benefit from “jumping the line” and starting with stronger medicines. The study is limited in that treatments were only compared over a 3 month trial period, and we cannot be certain that the patient populations were substantially similar as the comparative effectiveness was calculated.

That being said, this study will influence my practice. I will likely lean towards recommending more effective therapies with my future patients, including careful consideration of injections and diclofenac for moderate to severe OA, and ibuprofen/naproxen for mild to moderate OA, while shying away from celecoxib and acetaminophen altogether. And as we already know, glucosamine and chondroitin have been convincingly shown to be no better than placebo, so save your money on those pills. The racket is expected to blossom into a $20 billion dollar industry by 2020 if we don’t curb our appetite for expensive placebos.

In conclusion, the elephant in the room is that weight loss and exercise are still the very best treatments for knee osteoarthritis. Check out the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgery’s recent list of evidence-based recommendations for the treatment of knee arthritis for more information about the full spectrum of treatment options.

December 12th, 2014 by Dr. Val Jones in Expert Interviews, Health Tips

1 Comment »

I am proud to be a part of the American Resident Project, an initiative that promotes the writing of medical students, residents, and new physicians as they explore ideas for transforming American health care delivery. I recently had the opportunity to interview three of the writing fellows about how to help patients take control of their health. Dr. Marissa Camilon (MC) is an emergency medicine resident at LA County USC Medical Center, Dr. Craig Chen (CC) is an anesthesiology resident at Stanford Hospitals and Clinics, and Dr. Elaine Khoong (EK) is a resident in internal medicine at San Francisco General Hospital. Here’s what they had to say:

I am proud to be a part of the American Resident Project, an initiative that promotes the writing of medical students, residents, and new physicians as they explore ideas for transforming American health care delivery. I recently had the opportunity to interview three of the writing fellows about how to help patients take control of their health. Dr. Marissa Camilon (MC) is an emergency medicine resident at LA County USC Medical Center, Dr. Craig Chen (CC) is an anesthesiology resident at Stanford Hospitals and Clinics, and Dr. Elaine Khoong (EK) is a resident in internal medicine at San Francisco General Hospital. Here’s what they had to say:

1. How would you characterize the patients who are most successful at “taking charge of their health?”

MC: They are usually the the patients who aren’t afraid to ask questions about everything- possible treatments, pathology, risk factors.

EK: I think there are several traits that make patients successful at modifying their health: 1) Understanding of their disease: patients need to understand how their actions impact their health and be able to clearly identify the steps they need to take to achieve their desired health. 2) Possessing an internal locus of control: patients need to feel that their health is actually in their control. Oftentimes, patients who come from families that have a history of chronic diseases simply assume certain diseases may be their fate. But in reality, there are things that can be done to manage their disease. 3) Living in a supportive, nurturing environment: behavior changes are difficult. It is often not easy to the right thing for your health. Patients that take control of their health have a support system that helps ensure they take the steps they need. 4) Having realistic expectations: improving your health takes time and thus it requires patience. Individuals must be able to identify the baby steps that they’ve taken towards improving their health.

CC: Patients must collaborate with their physician – the best patients come in motivated, knowledgeable, and educated so they can have a meaningful dialogue with their doctor. Medical decision making is a conversation; patients who are invested in their health but also open to their doctor’s suggestions often have the best experiences.

2. What do you see as the main causes of non-adherence to medical advice/plans?

MC: Not fully understanding his or her own disease process, denial/shock, inability to pay for appointments/rides/medications.

EK: I think there are several reasons that patients may be non-adherent. These reasons can largely be grouped into three main categories — knowledge, attitude, and environmental factors. Some patients simply don’t understand the instructions provided to them. Providers haven’t made it clear the steps that need to be taken for patients to adhere. In other cases, patients may simply not believe that the advice provided will make an impact on their health. Probably most frequently, there are environmental factors that prevent patients from adhering to plans. Following medical advice often requires daily vigilance and strong will power. The challenges of daily life can make adherence difficulty.

CC: In my mind, non-adherence is not a problem with a patient, but instead a problem with the system. Modern medicine is a complex endeavor, and patients can be on a dozen different medications for as many medical problems. It’s unreasonable to expect someone to keep up with that kind of regimen. Socioeconomic factors also play a big role with adherence. Patients who are poor struggle to maintain housing, feed their children, hold a job; how can we expect them to be perfectly medically compliant? Tackling the issue of non-adherence requires engagement into the medical and social factors that pose challenges for patients.

3. Could mobile health apps help your patients? Do you think “there’s an app for that” could revolutionize patient engagement or your interaction with your patients now or in the future?

MC: Apps, not necessarily. Most of patient population has limited knowledge of their mobile phones (if they even have mobile phones). If they do have a phone, its usually an older model that doesn’t allow apps.

EK: I absolutely think that mobile health apps could help my patients. I work at a clinic for an urban underserved population. For patients that work multiple part-time jobs to make ends meet, it is difficult to ask them to come into see a healthcare provider (particularly if the commute to see us requires 2+ bus rides). Unfortunately the patients who are working multiple jobs are often patients in their 40’s and 50’s when they start manifesting the early signs and symptoms of our most common chronic diseases (hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease). Mobile applications have great potential to simplify the way through which patients can receive medical guidance especially helping the patients who don’t have the luxury to seek medical advice during normal work hours.

CC: I think there is a role for technology in the delivery of modern medical care. However, we have to keep in mind that not everyone has access to smartphones, and often the most medically disadvantaged populations are those who need support the most. Although initially, technology seemed to put a barrier between the clinician and the patient, I think as devices become more prevalent and we become better at using them, we’ll be able to use these collaboratively. The main advantage of an “app” or device is giving the patient more control over their health; they can track their sleep, diet, exercise, medication adherence, and other aspects of their health and work with their doctor to optimize it.

4. Do you know of any programs to improve health literacy that have been particularly successful or innovative? If so, describe. If not, what kind of initiative do you think could make a difference for your patients?

MC: I know that some of the primary care clinics in the county have started using texting for appointments reminders. Texting seems to be more accessible to our county population.

EK: Unfortunately, off the top of my head, I cannot think of any great programs that have increased health literacy. Part of the reason for this is that we really don’t have a great sense of what levers increase literacy. Any initiative that will work best honestly depends on the individual patient — each patient has different barriers that limit their health literacy. For some patients, their limited English proficiency is the greatest barrier. For other patients, there are cultural beliefs that must be considered in delivering health content. And for some patients, numeracy or general literacy is an issue. Unfortunately, I think there is no one size fits all solution for addressing health literacy.

CC: I don’t think there’s any magic bullet for health literacy. Different communities, patient populations, and clinical settings merit different interventions. For example, tackling child obesity in a neighborhood with lots of fast food requires a different program than ensuring prenatal health in an immigrant community.

5. Are there generational differences in how your patients interact with the healthcare system? Describe.

MC: I tend to see older patients since they usually have more medical problems. They are more likely to have a primary care doctor; whereas younger patients don’t come in as often, but don’t usually have access to primary care.

EK: I think more than a generational difference there is actually a cultural and socioeconomic difference. Traditionally, we are taught or somehow led to believe that older patients are more likely to simply adhere to medical advice whereas younger patients question. But in my limited experience, I have seen affluent patients more engaged with providers (bringing in their own resources, asking about health advice they’ve heard or read about). Some of my less wealthy patients seem more passive about their health and during visits. Furthermore, patients from certain cultural backgrounds are more or less likely to view healthcare providers as an authoritative figure rather than a partner in shared decision making.

6. Do you use digital systems (EMR/Social Media/Mobile) to interact with your patients in any way? Do you think you should do more of that, or that there is a desire for more on the part of your patients?

MC: We do have an EMR but don’t really use it to interact with patients. As I mentioned before, mobile texting may encourage patient interaction.

EK: The main way that I currently use digital systems to interact with patients is via email. Our clinic has a somewhat difficult-to-navigate telephone prompt system, so some patients email me directly re: changing their appointments, medical advice, or medication refills. Unfortunately our EMR doesn’t currently have a patient portal (although it will be rolling this out soon). I think a patient portal is a great tool for helping patients stay more engaged in their healthcare.

I think there is a role for SMS messaging to remind patients about appointments, important medications, or other healthcare related notices. For the right patient population, I think this could make a big difference.

In general, I am a big proponent of technology. I don’t think it’s going to be a panacea for our many problems in the healthcare system, but I think there are very specific shortcomings that technology can help us address.

7. What would your patients say they needed in order to be better educated about their health and have more successful healthcare experiences?

MC: More time with their physicians, mainly.

EK: Almost certainly simply more time with healthcare providers to better explain their health issues as well as more time to explore shared decision making.

CC: There is a lot of information out there about common illnesses and diseases, but not all of it is accurate or up-to-date. One challenge for patients is identifying appropriate resources written in a manner that can be easily read and understood with content that has been reviewed by a physician or other health care expert.

8. If you could pick only 1 intervention that could improve the compliance of your patients with their care/meds, what would it be?

MC: Increase the amount of time physicians have to answer questions with patients and discuss medical treatment options with them.

EK: Wow, that’s a hard one. I struggle to answer questions like this because I strongly believe that each patient is so different. Any non-adherent patient has his or her own barrier to adherence. But I suppose if I had to pick something, it might be some form of weekly check-in with a health coach / community health worker / health group class that intimately knew what the most important steps would be to helping that one patient ensure better health.

CC: I think that social interventions make the most difference in the health of underserved populations. For example, stable housing, healthy meals, job security, and reduction in violent crime will improve health including medical compliance far more than any medicine- or technology-based intervention.

In my last blog post I discussed how harmful physician “thought leaders” can be when they are dismissive of the value of other specialists’ care. I must have touched a nerve, because a passionate discussion followed in the comments section. It seems that physicians (who spend most of their time involved in clinical work) are growing tired of the leadership decisions of those who engage in little to no patient care. Clinicians urge lawmakers to turn to practicing physicians for counsel, because those who are out of touch with patients lack real credibility as advisers.

In my last blog post I discussed how harmful physician “thought leaders” can be when they are dismissive of the value of other specialists’ care. I must have touched a nerve, because a passionate discussion followed in the comments section. It seems that physicians (who spend most of their time involved in clinical work) are growing tired of the leadership decisions of those who engage in little to no patient care. Clinicians urge lawmakers to turn to practicing physicians for counsel, because those who are out of touch with patients lack real credibility as advisers.

It’s no secret that medicine has become a highly specialized business. While generalists used to be in charge of most patient care 50 years ago, we have now splintered into extraordinarily granular specialties. Each organ system has its own specialty (e.g. gastroenterology, cardiology), and now parts of systems have their own experts (hepatologists, cardiac electrophysiologists) Even ophthalmologists have subspecialized into groups based on the part of the eye that they treat (retina specialists, neuro-ophthalmologists)!

It’s no secret that medicine has become a highly specialized business. While generalists used to be in charge of most patient care 50 years ago, we have now splintered into extraordinarily granular specialties. Each organ system has its own specialty (e.g. gastroenterology, cardiology), and now parts of systems have their own experts (hepatologists, cardiac electrophysiologists) Even ophthalmologists have subspecialized into groups based on the part of the eye that they treat (retina specialists, neuro-ophthalmologists)! Wear and tear on the knee joints creates pain for up to 40% of Americans over age 45. There are plenty of over-the-counter (OTC) and prescription (Rx) osteoarthritis treatments available, but how effective are they relative to one another? A

Wear and tear on the knee joints creates pain for up to 40% of Americans over age 45. There are plenty of over-the-counter (OTC) and prescription (Rx) osteoarthritis treatments available, but how effective are they relative to one another? A  I am proud to be a part of the

I am proud to be a part of the