May 5th, 2015 by Dr. Val Jones in Expert Interviews, Research

Tags: American Resident Project, Collaboration, DemoDay, Engineers, Healthcare Innovation, IdeaLabs, Medical Students, Washington University School of Medicine

1 Comment »

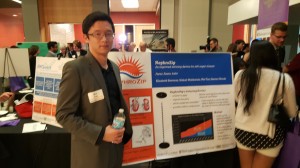

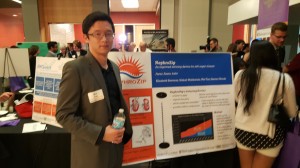

People's Choice Winning Idea: NephroZip

It’s no secret that doctors are disappointed with the way that the U.S. healthcare system is evolving. Most feel helpless about improving their work conditions or solving technical problems in patient care. Fortunately, one young medical student was undeterred by the mountain of disappointment carried by his senior clinician mentors and had the courage to tackle the problem head-on. Three years ago, Avik Som organized “Problem Day” at his medical school (Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, MO) and invited his professors to an unrestricted “open mic” venting session.

Representatives from the departments of surgery, medicine, pediatrics and neurology attended. They described their frustrations and day-to-day struggles with the students for 3 hours straight. After decades of service to suffering patients, it was the first time that anyone had asked them to share their own stories.

And borne out of this collective catharsis was IDEA Labs (a 501c3 ) – a student-driven movement to tackle clinician problems with fresh ideas and the energy of youth. I attended the third annual “DemoDay” (also known as “Solution Day”) presentations in St. Louis this week and was amazed by the breadth and depth of the student solutions to specific clinical problems. From plastic ties to hasten renal surgical procedures to energy efficiency units for hospital HVAC systems – the ideas spanned many technical knowledge domains, and investors in the audience paid rapt attention.

This year’s first-place winning idea was the Cystoview adaptor. Bladder scopes (or cystoscopes) represent a surprising 0.5% of Medicare’s total annual expenditures. Yet they still rely on old analogue technology and their images are difficult to share and transfer. The Cystoview device converts any cystocscope from analogue to digital, and images can be uploaded anywhere – from a desktop computer to a smart phone. Once collected, digital images can be mapped and reconstructed into a 3-D bladder scan so that surgeons can plan to more effective tumor resections. In addition, having the cystoscopes go wireless reduces the risk of infection associated with cords dragging across surgical fields.

IDEA Labs is unusual for several reasons. First, it was designed as a joint venture between professional schools at Washington University – Avik Som wanted to draw talent from Engineering, Business, Law, and Sciences to create multi-disciplinary student teams. The cross-pollination of student ideas can lead to some especially creative solutions.

Second, students retain 100% of the intellectual property associated with their solutions. So whether they design a specialized lumbar puncture chair, digital cystoscopy device, wheelchair storage mechanism, or new blood test for cancer, they are responsible for pitching their idea to angel investors and creating a business plan that will bring their ideas to market.

Third, IDEA Labs is student-driven, and therefore agile and independent from the administrative and political hurdles that can slow down innovation at academic medical centers.

Last year IDEA Labs students raised $300K in venture capital funding for their ideas. This year, they raised $1.5M. They are also actively franchising their student innovation model to other schools across the country.

Ramin Lalezari is a second year medical student and Director of Recruitment for IDEA Labs’ Executive Board. He is also an American Resident Project fellow (an organization that seeks out promising young medical students and residents and supports their writing talent – they also sponsored DemoDay this year). I got the chance to catch up with him at DemoDay. He described how he got involved with the project as a first year student, and worked with a team of engineers to design a system that detected pre-syncope in hospitalized patients, reducing the risk of possible falls.

“When I heard that medicine lags 50 years behind technology, I was horrified. Why do we still have pagers and fax machines?” huffed Lalezari. “We must do better. Students themselves will drive technology and innovation. We are going to build a network of incubators across the U.S., using telemedicine when appropriate. If a student in Los Angeles is passionate about solving a urology problem with engineers in St. Louis, then we will facilitate it. The student project manager pitches his idea, and students nationwide can sign up to help. Some of these design ideas are going to change the face of medicine. That’s our end game.”

I asked Lalezari if IDEA Labs would draw students away from practicing clinical medicine.

“There is no doubt that these projects require a time commitment. A few teams have disbanded due to the overwhelming burden of studying for exams. So some are quitting IDEA Labs. On the other hand, I’ve heard of some students who become so invested in their ideas that they talk about making a career out of it.”

“Are other medical schools developing their own IDEA Labs model for entrepreneurship?” I asked.

“There are 24-hr ‘hackathon’ models out there, and senior design projects that are formalized courses. IDEA Labs projects are 9 months long, with mentor-guided progress reports every 2 months. Most schools foster entrepreneurship from the top down – administrators and professors drive the ideas and the schools retain the intellectual property. I think that the bottom up approach resonates much more strongly with students.”

IDEA Labs may have turned the long-entrenched apprenticeship model of healthcare innovation on its head. No longer are students vying for the honor of supporting the design ideas of senior physicians in unpaid or underpaid internships. They are identifying problems and solving them in teams of peers without the hierarchy imposed by academic-driven projects. They have leveled the playing field and stand to gain a lot more from their hard work than ever before.

Although medicine may still be a dinosaur when it comes to technology adoption and innovation, the IDEA Labs students are replacing the soloist T. Rexes with team-working Raptors. And that represents a true leap forward in the evolution of healthcare.

***Demo Day was sponsored by The American Resident Project and J&J Innovation. For more information about how to get your school involved with IDEA Labs, please contact wustl.ideas@gmail.com.

December 12th, 2014 by Dr. Val Jones in Expert Interviews, Health Tips

Tags: Apps, Empowered Patients, EMR, Health Outcomes, Mobile Health, Poverty, Texting, The American Resident Project

1 Comment »

I am proud to be a part of the American Resident Project, an initiative that promotes the writing of medical students, residents, and new physicians as they explore ideas for transforming American health care delivery. I recently had the opportunity to interview three of the writing fellows about how to help patients take control of their health. Dr. Marissa Camilon (MC) is an emergency medicine resident at LA County USC Medical Center, Dr. Craig Chen (CC) is an anesthesiology resident at Stanford Hospitals and Clinics, and Dr. Elaine Khoong (EK) is a resident in internal medicine at San Francisco General Hospital. Here’s what they had to say:

I am proud to be a part of the American Resident Project, an initiative that promotes the writing of medical students, residents, and new physicians as they explore ideas for transforming American health care delivery. I recently had the opportunity to interview three of the writing fellows about how to help patients take control of their health. Dr. Marissa Camilon (MC) is an emergency medicine resident at LA County USC Medical Center, Dr. Craig Chen (CC) is an anesthesiology resident at Stanford Hospitals and Clinics, and Dr. Elaine Khoong (EK) is a resident in internal medicine at San Francisco General Hospital. Here’s what they had to say:

1. How would you characterize the patients who are most successful at “taking charge of their health?”

MC: They are usually the the patients who aren’t afraid to ask questions about everything- possible treatments, pathology, risk factors.

EK: I think there are several traits that make patients successful at modifying their health: 1) Understanding of their disease: patients need to understand how their actions impact their health and be able to clearly identify the steps they need to take to achieve their desired health. 2) Possessing an internal locus of control: patients need to feel that their health is actually in their control. Oftentimes, patients who come from families that have a history of chronic diseases simply assume certain diseases may be their fate. But in reality, there are things that can be done to manage their disease. 3) Living in a supportive, nurturing environment: behavior changes are difficult. It is often not easy to the right thing for your health. Patients that take control of their health have a support system that helps ensure they take the steps they need. 4) Having realistic expectations: improving your health takes time and thus it requires patience. Individuals must be able to identify the baby steps that they’ve taken towards improving their health.

CC: Patients must collaborate with their physician – the best patients come in motivated, knowledgeable, and educated so they can have a meaningful dialogue with their doctor. Medical decision making is a conversation; patients who are invested in their health but also open to their doctor’s suggestions often have the best experiences.

2. What do you see as the main causes of non-adherence to medical advice/plans?

MC: Not fully understanding his or her own disease process, denial/shock, inability to pay for appointments/rides/medications.

EK: I think there are several reasons that patients may be non-adherent. These reasons can largely be grouped into three main categories — knowledge, attitude, and environmental factors. Some patients simply don’t understand the instructions provided to them. Providers haven’t made it clear the steps that need to be taken for patients to adhere. In other cases, patients may simply not believe that the advice provided will make an impact on their health. Probably most frequently, there are environmental factors that prevent patients from adhering to plans. Following medical advice often requires daily vigilance and strong will power. The challenges of daily life can make adherence difficulty.

CC: In my mind, non-adherence is not a problem with a patient, but instead a problem with the system. Modern medicine is a complex endeavor, and patients can be on a dozen different medications for as many medical problems. It’s unreasonable to expect someone to keep up with that kind of regimen. Socioeconomic factors also play a big role with adherence. Patients who are poor struggle to maintain housing, feed their children, hold a job; how can we expect them to be perfectly medically compliant? Tackling the issue of non-adherence requires engagement into the medical and social factors that pose challenges for patients.

3. Could mobile health apps help your patients? Do you think “there’s an app for that” could revolutionize patient engagement or your interaction with your patients now or in the future?

MC: Apps, not necessarily. Most of patient population has limited knowledge of their mobile phones (if they even have mobile phones). If they do have a phone, its usually an older model that doesn’t allow apps.

EK: I absolutely think that mobile health apps could help my patients. I work at a clinic for an urban underserved population. For patients that work multiple part-time jobs to make ends meet, it is difficult to ask them to come into see a healthcare provider (particularly if the commute to see us requires 2+ bus rides). Unfortunately the patients who are working multiple jobs are often patients in their 40’s and 50’s when they start manifesting the early signs and symptoms of our most common chronic diseases (hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease). Mobile applications have great potential to simplify the way through which patients can receive medical guidance especially helping the patients who don’t have the luxury to seek medical advice during normal work hours.

CC: I think there is a role for technology in the delivery of modern medical care. However, we have to keep in mind that not everyone has access to smartphones, and often the most medically disadvantaged populations are those who need support the most. Although initially, technology seemed to put a barrier between the clinician and the patient, I think as devices become more prevalent and we become better at using them, we’ll be able to use these collaboratively. The main advantage of an “app” or device is giving the patient more control over their health; they can track their sleep, diet, exercise, medication adherence, and other aspects of their health and work with their doctor to optimize it.

4. Do you know of any programs to improve health literacy that have been particularly successful or innovative? If so, describe. If not, what kind of initiative do you think could make a difference for your patients?

MC: I know that some of the primary care clinics in the county have started using texting for appointments reminders. Texting seems to be more accessible to our county population.

EK: Unfortunately, off the top of my head, I cannot think of any great programs that have increased health literacy. Part of the reason for this is that we really don’t have a great sense of what levers increase literacy. Any initiative that will work best honestly depends on the individual patient — each patient has different barriers that limit their health literacy. For some patients, their limited English proficiency is the greatest barrier. For other patients, there are cultural beliefs that must be considered in delivering health content. And for some patients, numeracy or general literacy is an issue. Unfortunately, I think there is no one size fits all solution for addressing health literacy.

CC: I don’t think there’s any magic bullet for health literacy. Different communities, patient populations, and clinical settings merit different interventions. For example, tackling child obesity in a neighborhood with lots of fast food requires a different program than ensuring prenatal health in an immigrant community.

5. Are there generational differences in how your patients interact with the healthcare system? Describe.

MC: I tend to see older patients since they usually have more medical problems. They are more likely to have a primary care doctor; whereas younger patients don’t come in as often, but don’t usually have access to primary care.

EK: I think more than a generational difference there is actually a cultural and socioeconomic difference. Traditionally, we are taught or somehow led to believe that older patients are more likely to simply adhere to medical advice whereas younger patients question. But in my limited experience, I have seen affluent patients more engaged with providers (bringing in their own resources, asking about health advice they’ve heard or read about). Some of my less wealthy patients seem more passive about their health and during visits. Furthermore, patients from certain cultural backgrounds are more or less likely to view healthcare providers as an authoritative figure rather than a partner in shared decision making.

6. Do you use digital systems (EMR/Social Media/Mobile) to interact with your patients in any way? Do you think you should do more of that, or that there is a desire for more on the part of your patients?

MC: We do have an EMR but don’t really use it to interact with patients. As I mentioned before, mobile texting may encourage patient interaction.

EK: The main way that I currently use digital systems to interact with patients is via email. Our clinic has a somewhat difficult-to-navigate telephone prompt system, so some patients email me directly re: changing their appointments, medical advice, or medication refills. Unfortunately our EMR doesn’t currently have a patient portal (although it will be rolling this out soon). I think a patient portal is a great tool for helping patients stay more engaged in their healthcare.

I think there is a role for SMS messaging to remind patients about appointments, important medications, or other healthcare related notices. For the right patient population, I think this could make a big difference.

In general, I am a big proponent of technology. I don’t think it’s going to be a panacea for our many problems in the healthcare system, but I think there are very specific shortcomings that technology can help us address.

7. What would your patients say they needed in order to be better educated about their health and have more successful healthcare experiences?

MC: More time with their physicians, mainly.

EK: Almost certainly simply more time with healthcare providers to better explain their health issues as well as more time to explore shared decision making.

CC: There is a lot of information out there about common illnesses and diseases, but not all of it is accurate or up-to-date. One challenge for patients is identifying appropriate resources written in a manner that can be easily read and understood with content that has been reviewed by a physician or other health care expert.

8. If you could pick only 1 intervention that could improve the compliance of your patients with their care/meds, what would it be?

MC: Increase the amount of time physicians have to answer questions with patients and discuss medical treatment options with them.

EK: Wow, that’s a hard one. I struggle to answer questions like this because I strongly believe that each patient is so different. Any non-adherent patient has his or her own barrier to adherence. But I suppose if I had to pick something, it might be some form of weekly check-in with a health coach / community health worker / health group class that intimately knew what the most important steps would be to helping that one patient ensure better health.

CC: I think that social interventions make the most difference in the health of underserved populations. For example, stable housing, healthy meals, job security, and reduction in violent crime will improve health including medical compliance far more than any medicine- or technology-based intervention.

May 5th, 2014 by Dr. Val Jones in Expert Interviews, Health Policy, Opinion

Tags: Anesthesiologists, Freedom, Hospitalists, ICU, Intensivists, Job satisfaction, Locum Tenens, Physicians, Temp Work

1 Comment »

It’s no secret that most physicians are unhappy with the way things are going in healthcare. Surveys report high levels of job dissatisfaction, “burn out” and even suicide. In fact, some believe that up to a third of the US physician work force is planning to leave the profession in the next 3 years – an alarming statistic.

It’s no secret that most physicians are unhappy with the way things are going in healthcare. Surveys report high levels of job dissatisfaction, “burn out” and even suicide. In fact, some believe that up to a third of the US physician work force is planning to leave the profession in the next 3 years – an alarming statistic.

Direct primary care practices are touted as the best way to restore patient and provider satisfaction. Those brave enough to cut out the “middle man” (i.e. health insurers, both public and private) find a remarkable reduction in billing paperwork, unrecovered fees, and electronic documentation requirements. I know many physicians who have made the switch and are extremely happy to be able to spend most of their time in direct patient care, unfettered by most rules, regulations, and coding systems. They can solve problems via phone, email, text, video chat, or in-office as the need arises without having to worry about whether or not their manner of interaction will be reimbursed.

Direct primary care is probably the best way to find freedom and happiness in practicing outpatient medicine. But where does that leave physicians who are tied to hospital care due to the nature of their specialty (surgeons, intensivists, anesthesiologists, etc.)? Is there any way for them to find a brighter way forward?

I have found that working as a locum tenens hospital-based physician has dramatically improved my work satisfaction, and it may do so for you too. Here’s why:

1. You can take as much time off as you want, anytime you want. Do not underestimate the power of frequent vacations on your mental health. The frenetic pace of the hospital is much more tolerable in short doses. My attitude, stamina, and ability to stay focused is dramatically improved by working only 2-3 week stretches at a time. When I feel good, I can spread the cheerfulness, and I am happy to spend longer hours at work to give my patients more of my time.

2. You can avoid most political drama. Hospitals are incredibly stressful environments filled with hierarchical and territorial land mines. Being a short-timer allows you to avoid many conflicts. Administrators never nag you, or hold you responsible for perceived departmental deficiencies. You don’t need to attend committee meetings or become involved in personality quirk arbitrage. You can stay above the fray, focusing purely on the patients.

3. You learn all kinds of new things. Exposure to different patient populations, hospital expertise and different peer groups exposes you to a broader swath of technology and humanity. No longer will you be tied to the regional practice idiosyncrasies of a single hospital – you’ll learn how to tackle problems from many different angles. That knowledge earns you respect, and serves to cross-pollinate your own specialty, making you – and those you learn from – better doctors.

4. You are free to leave. There’s something refreshing about knowing that you can leave a place that you don’t like without any repercussions. No matter how unpleasant a locums assignment, it will end, and you can saunter off to brighter pastures.

5. You make more money. Believe it or not, locums work can be quite lucrative if you find the right assignments. I know a team of hospitalists who travel the country together, negotiating higher rates since they are a “one stop” solution. Their housing, travel, and cars are paid for by the agency, and they have take home pay (before taxes) around $350K per year. I personally think that working that many hours as a locum tenens physician kind of defeats the purpose of avoiding burn out, but some people like to do it that way.

6. You can live in the warm states in the winter, and the cold ones in the summer. Enough said.

7. You can try before you buy. Maybe you’re not sure where you want to sink down career roots. Or maybe you’re not sure you’ll like living in a certain city or part of the world? Maybe your family isn’t sure they want to move to a new location? Locum tenens assignments are the perfect way to try before you buy.

8. You can use your experience to become an excellent consultant. With long term exposure to various hospital systems, you are in a unique position to develop an encyclopedic knowledge of best practices. Sharing how other hospitals have solved their challenges can spark reform at other institutions. You can become a real force for positive change, not just on a micro level, but system and state-wide.

Working as a locum tenens physician may enhance your career satisfaction and promote professional advancement. What it will not solve, however, is the following:

1. You still have to work within the framework of bureaucracy endemic to hospitals. You’ll need to learn to use multiple different EMR systems and fill out most of the same paperwork that you do as a full-timer. This is painful at first, but once you’ve mastered the most common EMR systems (I’ve only really encountered 5 different ones in 2 years of locum tenens work) you’ll find a clinical rhythm that fits into most frameworks.

2. You will be living out of a suitcase. If the disruption of frequent travel is too much for you (or your family) to bear, then perhaps the locums lifestyle is not for you.

3. You will be annoyed by the process of getting multiple medical licenses and hospital credentialing. Agencies try to help with this burden, but mostly, you’ll need to suffer through this part yourself.

4. You will have to live with some degree of uncertainty. Part of the nature of working as a locum tenens physician is that clients (hospitals) change their minds frequently. They try to fill open positions with local staff or hire additional full-timers, using locums as their more expensive back ups. Assignments fall through frequently, so you’ll need to be ready to change course quickly.

Overall, I believe that locum tenens work can provide the practice freedom that many hospital-based physicians crave. If you’re eager to get off the unrelenting clinical treadmill, this is an easy way to do it. At a recent assignment near New Hampshire, I mused at the license plates that I passed on my way to work: “Live free or die” is their state motto. And I think it captures my sentiments exactly.

January 31st, 2014 by Dr. Val Jones in Expert Interviews

Tags: 2014, Centricity, Chief Medical Officer, CMO, Colorado, Emergencies, GE, Gloria Beim, Orthopedics, Russia, Sochi, Sports Medicine, Team USA, Winter Olympic Games, Winter Olympics

1 Comment »

I am a huge fan of the winter Olympics, partly because I grew up in Canada (where most kids can ski and skate before they can run) and partly because I used to participate in Downhill ski racing. Now that I’m a rehab physician (with a reconstructed knee) I’m thrilled to have the opportunity to interview Team USA’s Chief Medical Officer, Dr. Gloria Beim. As we enjoy the Sochi Olympic games via our TV sets, keep an eye out for Dr. Beim! Please read on to get her behind-the-scenes account of what it takes to care for and keep Team USA Olympians in tip top shape.

I am a huge fan of the winter Olympics, partly because I grew up in Canada (where most kids can ski and skate before they can run) and partly because I used to participate in Downhill ski racing. Now that I’m a rehab physician (with a reconstructed knee) I’m thrilled to have the opportunity to interview Team USA’s Chief Medical Officer, Dr. Gloria Beim. As we enjoy the Sochi Olympic games via our TV sets, keep an eye out for Dr. Beim! Please read on to get her behind-the-scenes account of what it takes to care for and keep Team USA Olympians in tip top shape.

Dr. Val: How did you become the Chief Medical Officer (CMO) for the U.S. winter Olympic team?

Dr. Beim: My practice, Alpine Orthopaedics, is located in an area of Colorado that attracts all levels of athletes, especially elite athletes. I initially entered the elite sports arena in a volunteer capacity at major ski and cycling competitions. Fortunately, my skills and knowledge were noticed at these competitions, which resulted in my servicing a number of medical teams that parlayed me into the world games and Olympic arena. I believe my collaborative, tireless work ethic led to being part of the 2004 and 2012 Olympic Games and as CMO of the 2011 Pan-American Games. Most recently, I was a physician at the World Cup Ski Championships in Beaver Creek, Colo. Between my private practice and my volunteering, I am honored to have been appointed CMO for the Sochi Olympic Winter Games.

Dr. Val: What does being CMO mean?

Dr. Beim: It means overseeing 77 other health care professionals and taking care of 228 U.S. Olympians. As CMO, I work in tandem with a team to deliver the highest level of care to our athletes. We are using the latest technology, evaluating a mix of treatments to ensure peak performance, and are ready to respond to whatever might come our way. It means working long and busy hours during the Games, where the team is faced with everything from common colds and illness to traumatic injury. It also means having compassion and understanding while applying your medical expertise in a fast-moving environment. The days can be long, but it is always rewarding to see our athletes rebound and put their best performance forward. It’s an honor to be a part of that process.

Dr. Val: Give me a “behind-the-scenes” description of what the medical support of the athletes looks like.

Dr. Beim: Well, it looks pretty much like any medical clinic you might be familiar with. There have been dozens of boxes shipped to Sochi in preparation for caring for our athletes. Our doctors can see everything from coughs and flu to sprains and breaks. As a result, we have a very comprehensive team assembled to address whatever health-related need might come through the door. We look at the mix of care providers, such as athletic trainers and physical therapists or chiropractors and massage therapists, to assess and provide the best solution to the problem. Our goal is to have our athletes back on the slope, track or rink as fast as possible, performing at their peak.

I have been learning to speak Russian to interact with local hospitals and facilities. We need to be able to communicate our needs quickly and accurately. At other Games, I have found learning the local language to be valuable in the overall care we can access for our athletes. In addition, it is a lot of fun! I really enjoy communicating with the locals and I know they enjoy it, too.

Dr. Val: Does each country bring their own EMS/MDs/coaches?

Dr. Beim: Many countries bring their own medical team, but not all. The athletes do have access to a polyclinic located at the villages, which can address most of the medical issues that can arise during the Games. These polyclinics are generally staffed with excellent physicians and specialists in many areas, as well as a lot of diagnostic equipment and a full pharmacy. Team USA also will have access to these great polyclinics; however, it is quite efficient and simple for our athletes to receive care and recovery modalities in our own sports medicine clinics.

Dr. Val: Who cares for the athletes if there is a life-threatening injury?

Dr. Beim: There would be a team effort between doctors/specialists/emergency providers from the Olympic Organizing Committee and our Team USA doctors. We feel confident that through our collaborative efforts, we will be able to care for our athletes in just about any situation.

Dr. Val: What kinds of on-site medical facilities are there (one at each event or just a centrally located area)?

Dr. Beim: We are fortunate to have a very comprehensive medical area to treat our athletes. There is a polyclinic at both the coastal village and the mountain village, which will have some imaging capabilities and several specialists as well as a pharmacy. We always will have one of our physicians with the team during training and competitions at the various sites. This gives us the flexibility to provide immediate care should the situation arise.

Dr. Val: How are injuries being prevented?

Dr. Beim: Preventing injury is part of the support we provide. Aiding athletes and coaches to condition appropriately and prime their bodies with good nutrition and recovery efforts while in Sochi is all part of the “whole” care we provide to Team USA. We can use technology to assess and evaluate to ensure our athletes are at their peak to perform. The travel and extreme competition can take a toll on a body. We do our best to keep the athletes healthy in every respect.

Dr. Val: Are there any new technologies being used by the US medical team in Sochi?

Dr. Val: Are there any new technologies being used by the US medical team in Sochi?

Dr. Beim: One of the tools we use is GE Healthcare’s Centricity software. This tool is really amazing and provides our physicians and athletes the ability to communicate health information instantaneously and securely. The software maintains diagnostics, treatment evaluations and test results, and it can all be accessed virtually. This is especially critical when you’re traveling from venue to venue in another country. I have implemented this same software in my private practice through Quatris Health. Now, no matter who is involved in the patient’s care, the health care professional has easy access to all the critical information and can respond accordingly. We also have several GE ultrasound machines that we travel with, which is an incredible diagnostic tool for many musculoskeletal injuries.

Dr. Val: How might other young physicians follow in your footsteps?

Dr. Beim: I would encourage any physician that aspires to this kind of appointment to begin connecting with officials in their area of interest. My work with the U.S. Cycling Team helped build my reputation among other elite sports organizations, where I was able to establish relationships and convey my interest in working with them. It can take a lot of time volunteering, but the work is invigorating and stimulating because you learn so much in the process. I really believe I am a better physician and surgeon because I have had the chance to work in these situations. I can bring that experience back to my private practice, which elevates care for everyone.

October 15th, 2013 by Dr. Val Jones in Expert Interviews

Tags: Advice, Healthcare Policy, Hospital Executives, Hospital Staffing, Locum Tenens, Locum Tenens Agency, Poor Matches, Problems, Retired Physicians, Salary Seekers, Traveling Physicians, Trends, Unhappy, Vacation Money

No Comments »

I recently wrote about my experiences as a traveling physician and how to navigate locum tenens work. Today I want to talk about the client (in this case, hospital) side of the equation. I’ve had the chance to speak with several executives (some were physicians themselves) about the overall process of hiring and managing temporary physicians. What I heard wasn’t pretty. I thought I’d summarize their opinions in the form of a mock composite interview to protect their anonymity – I’m hoping that locum MDs and agencies alike can learn from this very candid discussion.

I recently wrote about my experiences as a traveling physician and how to navigate locum tenens work. Today I want to talk about the client (in this case, hospital) side of the equation. I’ve had the chance to speak with several executives (some were physicians themselves) about the overall process of hiring and managing temporary physicians. What I heard wasn’t pretty. I thought I’d summarize their opinions in the form of a mock composite interview to protect their anonymity – I’m hoping that locum MDs and agencies alike can learn from this very candid discussion.

Dr. Val: How do you feel about Locum Tenens agencies?

Executive: They’re a necessary evil. We are desperate to fill vacancies and they find doctors for us. But they know we are desperate and they take full advantage of that.

Dr. Val: What do you mean?

Executive: They charge very high hourly rates, and they don’t care about finding the right fit for the job. They seem to have no interest in matching physician temperament with hospital culture. They are only interested in billable hours and warm bodies, unfortunately. But we know this going in.

Dr. Val: Do you try to screen the candidates yourself before they begin work at your hospital?

Executive: Yes, we carefully review all their CVs and we interview them over the phone.

Dr. Val: So does that help with finding better matches?

Executive: Not really. Everyone looks good on paper and they sound competent on the phone. You only really know what their work ethic is like once they’ve started seeing patients.

Dr. Val: What percent of locums physicians would you say are “sub-par” then?

Executive: About 50%.

Dr. Val: Whoah! That’s very high. What specifically is wrong with them? Are they poor clinicians or what?

Executive: It’s a lot of things. Some are poor clinicians, but more commonly they just don’t work very hard. They have this attitude that they only have to see “X” number of patients per day, no matter what the census. So they’re not good team players. Also many of them have prima donna attitudes. They just swish into our hospital and tell us how they like to do things. They have no problem complaining or calling out flaws in the system because they know they can walk away and never see us again.

Dr. Val: Yikes, they sound horrible. Looking back on those interviews that you did with them, could you see any of this coming? Are there red flags in retrospect?

Executive: None that I can think of. All of our problem locums have been very different – some are old, some are young – they come from very different backgrounds, cultures, and parts of the country. I can’t think of anything they had in common on paper or in the phone interviews.

Dr. Val: So maybe the agencies don’t screen them well?

Executive: Right. I think they probably ignore negative feedback about a physician and just “solve the problem” by not sending them back to the same hospital. They just send them elsewhere – and so the problem continues. They have no incentive really to take a locums physician out of circulation unless they do something truly dangerous at work (medical malpractice). That’s pretty rare.

Dr. Val: I recently wrote on my blog that there are 4 kinds of physicians who do locums: 1. Retirees, 2. Salary Seekers, 3. Dabblers and 4. Problem personalities – would you agree with those categories?

Executive: Yes, but I think that a large proportion of the locums I’ve met have been either motivated by money (i.e. they want to make some extra cash so they can go on a fancy vacation) or they just don’t get along well with others. There are more “problem people” out there than you think.

Dr. Val: This is rather depressing. Have you found that some agencies do a better job than others at keeping the “good” physicians coming?

Executive: Well, we only work with 2 or 3 agencies, so I can’t speak to the entire range of options. We just can’t handle the complexity associated with juggling too many recruiters at once because we end up with accidental overlap in contracts. We have booked two doctors via two different agencies for the same block of time and then we are legally bound to take them both. It’s an expensive mistake.

Dr. Val: Does one particular agency stand out to you in terms of quality of experience?

Executive: No. Actually they all seem about the same.

Dr. Val: For us locums doctors, I can tell you that agencies vary quite a bit in terms of quality of assignments and general process.

Executive: There may be a difference on your end, but not much on ours.

Dr. Val: So, being that using locums has been a fairly negative experience for you, what do you intend to do to change it?

Executive: We are trying very hard to recruit full time physicians to join our staff so that we reduce our need for locums docs. It’s not easy. Full time physician work has become, quite frankly, drudgery. Our system is so burdened with bureaucratic red tape, decreasing reimbursement, billing rules and government regulations that it sucks the soul right out of you. I don’t like who I become when I work full time. That’s why I had to take an administrative job. I still see patients part-time, but I can also get the mental and emotional break I need.

Dr. Val: So you’re actually a functional locums yourself, if not a literal one.

Executive: Yes, that’s right. I have some guilt about not working full time, and yet, I have to maintain my sanity.

Dr. Val: Given the generally negative work environment that physicians live in these days, I suppose that temporary work is only going to increase exponentially as others take the path that you and I have chosen?

Executive: With the looming physician shortage, rural centers in particular are going to have to rely more and more on locums agencies. What agencies really need to do to distinguish themselves is hire clinicians to help them screen and match locums to hospitals. Agencies don’t seem to really understand what we need or what the problems are with their people. If they had medical directors or a chief medical officer, people who have worked in the trenches and understand both the client side and the locum side, they would be much better at screening candidates and meeting our needs. Until then, we’re probably going to have to limp along with a 50% miss-match rate.

I am proud to be a part of the

I am proud to be a part of the

It’s no secret that most

It’s no secret that most

Dr. Val: Are there any new technologies being used by the US medical team in Sochi?

Dr. Val: Are there any new technologies being used by the US medical team in Sochi? I recently wrote about

I recently wrote about