August 17th, 2015 by Dr. Val Jones in True Stories

Tags: Abuse, Annals Of Internal Medicine, Child Rape, Essay, Misogyny, OB/GYN, Racism, Scandalous Physician Behavior, Sexism

26 Comments »

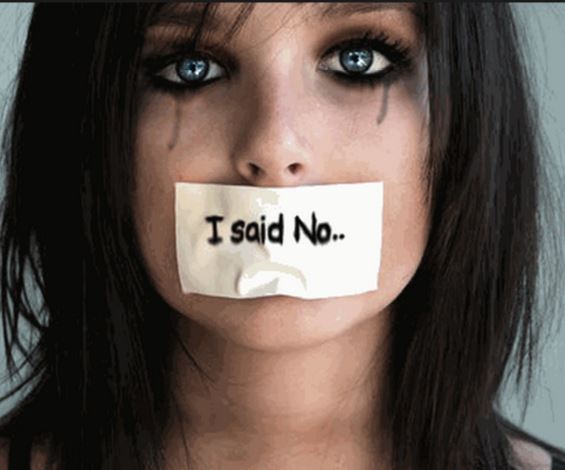

If you have not read the latest essay and editorial about scandalous physician behavior published in the Annals of Internal Medicine (AIM), you must do so now. They describe horrific racist and sexist remarks made about patients by senior male physicians in front of their young peers. The physicians-in-training are scarred by the experience, partially because the behavior itself was so disgusting, but also because they felt powerless to stop it.

If you have not read the latest essay and editorial about scandalous physician behavior published in the Annals of Internal Medicine (AIM), you must do so now. They describe horrific racist and sexist remarks made about patients by senior male physicians in front of their young peers. The physicians-in-training are scarred by the experience, partially because the behavior itself was so disgusting, but also because they felt powerless to stop it.

It is important for the medical community to come together over the sad reality that there are still some physicians and surgeons out there who are wildly inappropriate in their patient care. In my lifetime I have seen a noticeable decrease in misogyny and behaviors of the sort described in the Annals essay. I have written about racism in the Ob/Gyn arena on my blog previously (note that the perpetrators of those scandalous acts were women – so both genders are guilty). But there is one story that I always believed was too vile to tell. Not on this blog, and probably not anywhere. I will speak out now because the editors at AIM have opened the conversation.

When I was a third-year medical student I was assigned to tag along with an ophthalmology resident serving his first year of residency as an intern in general surgery. We were to cover the ER consult service one night, and our first patient was a young Hispanic girl with abdominal pain. It was suspected that she may have had appendicitis. Part of the physical exam required that we rule out a gynecologic cause of the pain. And so a pelvic exam was planned for this young girl of about 12 or 13. She was frightened and clinging to her grandmother. She had never seen a gynecologist before and had explained through her grandmother that she was a virgin – making a gynecologic cause of her abdominal pain less likely. I offered her some reassurance with my broken Spanish and held her hand as we wheeled her on a stretcher to a private examining room. The resident whispered in my ear, “This is going to be fun.”

The resident was creepy at every stage of the exam. He was clearly relishing the process, slowly instructing the poor girl to position herself correctly on the table. He held her knees apart as she whimpered and cried. He pretended to have difficulty positioning the speculum, inserting and reinserting it an unconscionable number of times. All-in-all it probably took ten minutes for him to get a cervical sample (this usually takes under 60 seconds). He performed the bi-manual portion of the exam in a bizarre, sexualized manner. I was furious and nauseated.

The patient was finally returned to her grandmother and the resident took me aside to ask how I thought he did. The perverted expression on his face was not lost on me. I looked at him with daggers in my eyes, but I knew that if I confronted him head-on it could trigger an investigation and in the end I had no hard evidence to prove that he had done anything wrong. It would wind up being a “he said, she said” scenario. I mustered the courage to say, “I think you were slow.”

For a fleeting moment he was taken aback by my insubordinate criticism and then he said the sentence that still haunts me today, “Well it was her first time.”

Each time I think of this interaction I feel sick to my stomach. I wonder what more I could have done.* I wonder if he is still out there violating his patients, and if anyone has ever confronted him. My only consolation, I suppose, is that he did not go on to become an Ob/Gyn. As an ophthalmologist one would hope that he had fewer opportunities for sexual abuse of patients.

I guess you could say that in my medical training, I witnessed a child rape. I don’t think it gets much worse than that… and I don’t know what to do with this horrific memory. I am forever changed.

It is my hope that these sorts of situations become true “never events” and that we create a protective environment where there are no career consequences for medical students thrust into the unfortunate position of whistle blower. Maybe the courageous AIM editorial is the first step towards redemption and healing.

*Note that I never saw this resident again. Our paths did not cross after the incident, and it was only at the end of the exam that I fully recognized the evil of his intent.

August 5th, 2015 by Dr. Val Jones in True Stories

Tags: Anxiety, Bedside Manner, Genetic Testing, Healthcare Quality, Oncology, Testing

No Comments »

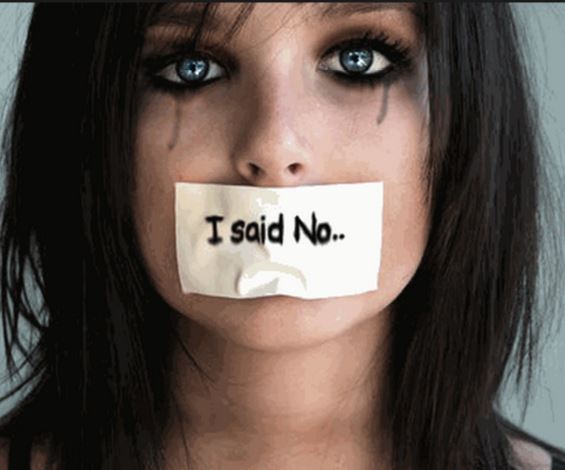

A wrist graft similar to what my friend's husband required.

I watched helplessly as a dear friend went through the emotional meat grinder of a new cancer diagnosis. Her husband was found to have melanoma on a recent skin biopsy, and she knew that this was a dangerous disease. Because she is exceptionally intelligent and diligent, she set out to optimize his outcome with good information and the best care possible. Without much help from me, she located the finest specialists for her husband, and ultimately he received appropriate and state-of-the-art treatment. But along with his excellent care came substantial (and avoidable) emotional turmoil. The art of medicine was abandoned as the science marched on.

First came the pathology report, detailed and nuanced, but largely uninterpretable for the lay person. She received a copy of it at her request, but without any attempt at translation by her physician. In his view, she shouldn’t be looking at it at all, since it was up to him to decide next steps. She brought the report to me, wondering if I could make heads or tails out of it. Although I am not trained in pathology, I did know enough to be able to translate it, line-by-line, into normal speak. This was of great comfort to her as the ambiguity of prognosis (rather than certainty of metastasis and or mortality, etc.) was clearly outlined for the trained eye.

Then came the genetic testing and node biopsy. She was told that the tests could identify variants that would portend poorer outcomes, though it would take 6 weeks to find out if he had “the bad kind of melanoma.” Those 6 weeks were excruciating for her, as she planned out how they would manage financially if he needed treatment for metastatic disease, and if his life were shortened by various numbers of years. At week 6 they received no word from the physician, and so she called the office to inquire about how much longer it would take for the genetic testing to come back. She was rebuffed by office staff and was instructed to be patient because the lab was “processing an unusual number of samples” at this time.

Another week of anguish passed and she decided to contact the lab directly. As it turned out, they were eagerly awaiting the arrival of her husband’s sample, but it had been “lost” in hospital processing somehow. She called the hospital’s facility and someone found the tissue under a pile of other samples and tagged it appropriately and sent it on to the genetics lab. The hospital apologized for the delay via email – and she forwarded the note to her oncologist, so that he could sort out the potential processing bottleneck for other patients going forward.

The result was reported to the oncologist within a week’s time and in turn, the physician called (at 6:30am on a Monday morning) to discuss the result with my friend’s husband. He missed the call as he was in the shower getting ready for work, and wound up playing phone tag with the physician’s office for 3 more days. My friend had her heart in her mouth the entire time. She continued to imagine a world without her husband. If the disease stole him from her, how would she manage? What about the children? Could she make enough money alone to support her family?

“Why didn’t the physician leave any hint of the result in the phone message? If it was good news, surely he would have mentioned that.” She presumed. The physician required his patient to come into the office to discuss the results. And so they booked the next available time slot, another couple of days later. My friend was certain this was a bad sign.

As they arrived at the oncologist’s office, the staff forbade my friend to accompany her husband to the meeting. “Clinic policy” they stated. My friend’s mind was now spinning out of control – maybe my husband needs to be alone with the doctor because the results are so devastating that he must hear it by himself?

She insisted, nonetheless, to accompany him – and the staff felt obligated to clear it with the oncologist before they allowed her to enter the examining room with her husband. They whispered to him in another room before giving her the irritated nod that she could proceed. You could have cut the tension with a knife… she was certain that a death sentence was about to be handed down.

Once the oncologist entered the room, he spent the first 10 minutes making excuses for the delay in genetic tissue results. He argued that the hospital lab was actually not at fault for the delay and listed all the various reasons why nothing had been done incorrectly. His was so single-mindedly focused on the email he received weeks prior (simply describing the delay — as if it were some kind of assault on his own competency) that he almost left the room without telling them the results of the genetic test and biopsy sample.

As an afterthought at the end of the meeting, he announced: “Oh, and the tests suggest that you have a melanoma that is extremely unlikely to metastasize. The wide excisional biopsy is likely curative.”

And off he swished, white coat flowing behind him as he flung wide the door and moved on to the next patient.

The irony is that my friend’s husband got “great” medical care with a large helping of unnecessary suffering. His initial biopsy, wide excision and skin grafting, lymph node testing, and genetic lab studies were all appropriate and helpful in his diagnosis and treatment. But the way in which the information was presented (or not presented) was what made the entire process so painful. Unfortunately, we spend most of our time as physicians focused on the technicalities of what we do, rather than the emotional consequences they have on our patients and their families.

As we continue to “deliver healthcare” to our patients, let’s remember not to serve up any sides of unnecessary mental anguish. Clear and timely communication makes a world of difference in patient anxiety levels. And reducing those is part of the art of medicine that is so desperately needed, and disturbingly rare these days.

July 27th, 2015 by Dr. Val Jones in Health Tips, True Stories

Tags: Blood Tests, Correct Diagnosis, False Negatives, False Positives, Lab Tests, Physical Exam, Radiology, Trust

2 Comments »

I met my newly admitted patient in the quiet of his private room. He was frail, elderly, and coughing up gobs of green phlegm. His nasal cannula had stepped its way across his cheek during his paroxsysms and was pointed at his right eye. Although the room was uncomfortably warm, he was shivering and asking for more blankets. I could hear his chest rattling across the room.

I met my newly admitted patient in the quiet of his private room. He was frail, elderly, and coughing up gobs of green phlegm. His nasal cannula had stepped its way across his cheek during his paroxsysms and was pointed at his right eye. Although the room was uncomfortably warm, he was shivering and asking for more blankets. I could hear his chest rattling across the room.

The young hospitalist dutifully ordered a chest X-Ray (which showed nothing of particular interest) and reported to me that the patient was fine as he was afebrile and his radiology studies were unremarkable. He would stop by and check in on him in the morning.

I shook my head in wonderment. One look at this man and you could tell he was teetering on the verge of sepsis, with a dangerous and rather nasty pneumonia on physical exam, complicated by dehydration. I started antibiotics at once, oxygen via face mask, IV fluids and drew labs to follow his white count and renal function. He perked up nicely as we averted catastrophe overnight. By the time the hospitalist arrived the next day, the patient was looking significantly better. The hospitalist left a note in the EMR about a chest cold and zipped off to see his other new consults.

Similar scenarios have played out in countless cases that I’ve encountered. Take, for example, the man whose MRI was “normal” but who had new onset hemiparesis, ataxia, and sensory loss on physical exam… The team assumed that because the MRI did not show a stroke, the patient must not have had one. He was treated for a series of dubious alternative diagnoses, became delirious on medications, and was reassessed only when a family member put her foot down about his ability to go home without being able to walk. A later MRI showed the stroke.

A woman with gastrointestinal complaints was sent to a psychiatrist for evaluation after a colonoscopy and endoscopy were normal. After further blood tests were unremarkable, she was provided counseling and an anti-depressant. A year later, a rare metastatic cancer was discovered on liver ultrasound.

Physicians have access to an ever-growing array of tests and studies, but they often forget that the results may be less sensitive or specific than their own eyes and ears. And when the two are in conflict (i.e. the patient looks terrible but the test is normal), they often default to trusting the tests.

My plea to physicians is this: Listen to your patients, trust what they are saying, then verify their complaints with your own exam, and use labs and imaging sparingly to confirm or rule out your diagnosis. Understand the limitations of each study, and do not dismiss patient complaints too easily. Keep probing and asking questions. Learn more about their concerns – open your mind to the possibility that they are on to something. Do not blame the patient because your tests aren’t picking up their problem.

And above all else – trust yourself. If a patient doesn’t look well – obey your instincts and do not walk away because the tests are “reassuring.” Cancer, strokes, and infections will get their dirty tendrils all over your patient before that follow up study catches them red handed. And by then, it could be too late.

July 4th, 2015 by Dr. Val Jones in Research, True Stories

Tags: Communications, Culture Of Carefulness, Don't Get Sick In July, Handoffs, Interns, Medical Errors, Mistakes, Sign out, The July Effect

2 Comments »

Photo By Danny Kim

The short answer, in my opinion, is yes.

The long answer is slightly more nuanced. As it turns out, studies suggest that one’s relative risk of death is increased in teaching hospitals by about 4-12% in July. That likely represents a small, but significant uptick in avoidable errors. It has been very difficult to quantify and document error rates related to inexperience. Intuitively we all know that professionals get better at what they do with time and practice… but how bad are doctors when they start out? Probably not equally so… and just as time is the best teacher, it is also the best weeder. Young doctors with book smarts but no clinical acumen may drop out of clinical medicine after a short course of doctoring. But before they do, they may take care of you or your loved ones.

It has been argued that young trainees “don’t practice in a vacuum” but are monitored by senior physicians, pharmacists, and nurses and therefore errors are unlikely. While I agree that this oversight is necessary and worthwhile, it is ultimately insufficient. Let me provide an illustrative example.

When I was a new intern I was assigned to a patient with curious eyelids. He was a mildly obese, middle aged man with a beard who spoke in hushed tones. What struck me the most was that he had voluminous upper eyelids. They were so strange that I couldn’t stop staring at them. He didn’t have any hives or red blotches on his skin, and his eyeballs were clear and white. There was no pus or discharge of any kind. I was so perplexed that I began to search through his medical record for answers before I embarrassed myself by asking for a consult. After many hours of digging, I discovered the smoking gun.

Apparently, he had been given repeat boluses of 1 Liter of IV normal saline by dutiful interns and residents who had not communicated with one another about who would write the order. So they all did. This man was so fluid overloaded that his eyes were literally bugging out of his head. No one had noticed the edema because of his size, and because (thank God) his heart and kidneys were young and healthy enough to handle the load without going into outright failure. Also, normal saline is such an innocuous medication that it didn’t flag any concerns by the nurses (who were also rotating through the service and busy swatting the more obvious mistakes being made by the fresh crop of interns).

If this poor patient had congestive heart failure or kidney disease, he could have been killed by well-meaning, diligent interns with salt water. Fortunately for him, he made a full recovery – and because there was technically “no harm done” I don’t even think this case was discussed in M&M (morbidity and mortality) conference, and I also doubt that anyone was reprimanded. Sounds crazy, but there are bigger fish to fry in July.

So my point is this: rookie mistakes are not always tracked, documented, addressed, or perhaps even noted. But they are real. They are scary. And they are lurking at every teaching hospital in this country. We must all remain on high alert – and question everything. Because even eyelids offer important clues, and water can kill.

***

If you or a loved one insist on falling ill in July, I recommend finding a hospital with a culture of carefulness or bring a patient advocate with you.

If you have not read the latest essay and editorial about scandalous physician behavior published in the Annals of Internal Medicine (AIM), you must do so now. They describe horrific racist and sexist remarks made about patients by senior male physicians in front of their young peers. The physicians-in-training are scarred by the experience, partially because the behavior itself was so disgusting, but also because they felt powerless to stop it.

If you have not read the latest essay and editorial about scandalous physician behavior published in the Annals of Internal Medicine (AIM), you must do so now. They describe horrific racist and sexist remarks made about patients by senior male physicians in front of their young peers. The physicians-in-training are scarred by the experience, partially because the behavior itself was so disgusting, but also because they felt powerless to stop it.

I met my newly admitted patient in the quiet of his private room. He was frail, elderly, and coughing up gobs of green phlegm. His nasal cannula had stepped its way across his cheek during his paroxsysms and was pointed at his right eye. Although the room was uncomfortably warm, he was shivering and asking for more blankets. I could hear his chest rattling across the room.

I met my newly admitted patient in the quiet of his private room. He was frail, elderly, and coughing up gobs of green phlegm. His nasal cannula had stepped its way across his cheek during his paroxsysms and was pointed at his right eye. Although the room was uncomfortably warm, he was shivering and asking for more blankets. I could hear his chest rattling across the room.