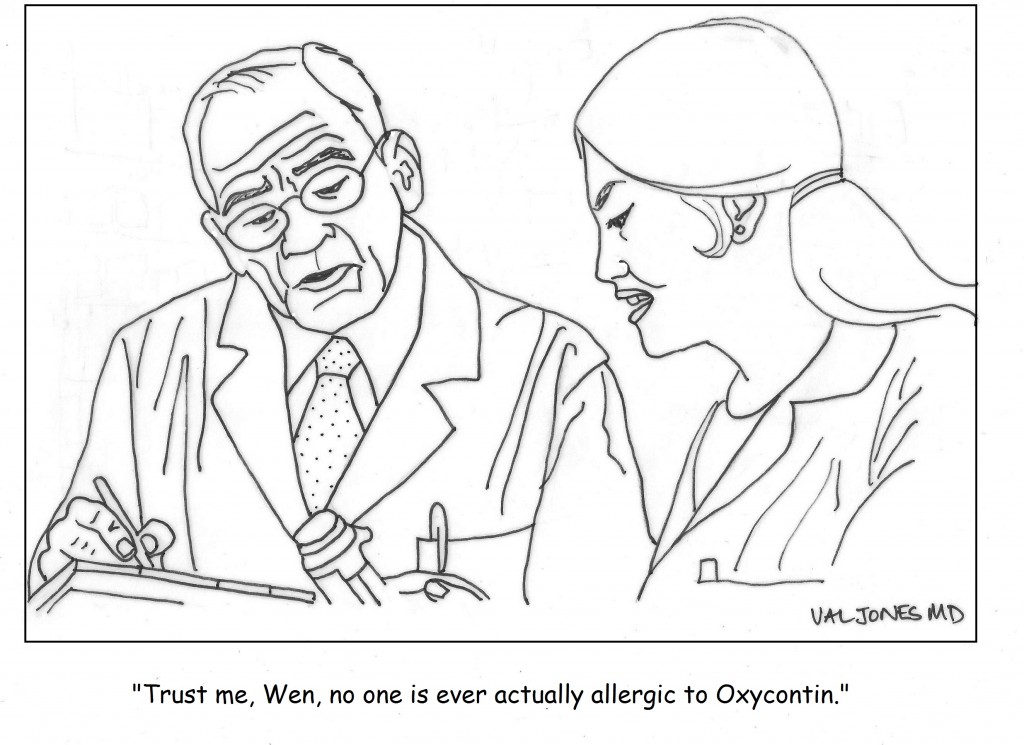

Cartoon: America’s Problem With Pain Meds

The digital revolution in healthcare has transformed most hospitals into EMR-dependent worksites, dotted with computer terminals that receive more attention than the patients themselves. I admit that my own yearning for the “good old days” was beginning to wane, as my memory of paper charting and a patient-focused culture was becoming a distant memory. That is, until I filled in for a physician at a rural hospital where digital mandates, like a bad zombie movie, had bitten their victim but his full conversion to undead status had not been completed. At this hospital in its “incubation period,” electronic records consisted of collated scans of hand-written notes, rather than auto-populated templates. I’m not necessarily recommending the return of the microfiche, but what I experienced in this environment surprised me.

The digital revolution in healthcare has transformed most hospitals into EMR-dependent worksites, dotted with computer terminals that receive more attention than the patients themselves. I admit that my own yearning for the “good old days” was beginning to wane, as my memory of paper charting and a patient-focused culture was becoming a distant memory. That is, until I filled in for a physician at a rural hospital where digital mandates, like a bad zombie movie, had bitten their victim but his full conversion to undead status had not been completed. At this hospital in its “incubation period,” electronic records consisted of collated scans of hand-written notes, rather than auto-populated templates. I’m not necessarily recommending the return of the microfiche, but what I experienced in this environment surprised me.

1. Everyone read my notes. Because everything I wrote was relevant (not just a re-hash of data from another part of the medical record), reading became high-yield. Just as people have adapted to ignoring internet advertising (Does anyone even look at the right hand rails of web pages anymore?), EMR-users have become accustomed to skimming and ignoring notes because the “nuggets” of useful input are so sparse and difficult to find that no has time to do so. The entire team was more informed and up to date with my treatment plan because they could easily read what I was thinking.

2. I was able to draw diagrams again. Sometimes a picture is worth 1000 words – and when given a pen and paper, it is great to have the chance to quickly draw a wound site, or visually capture the anatomical concerns a patient may have, or even add an arrow, underline, or circle for emphasis. Thorough neuro exams are so much easier to document with stick figures and motor scores/reflexes added.

3. I could see at a glance if a consultant had stopped by to see a patient. It used to be customary for specialists to leave a note in the paper record immediately after examining a patient. If they didn’t have time to jot down a full consult, they would at least leave me their summary statement – with critical conclusions and next steps. It was a real time-saver to know when a consulting physician had evaluated a patient and get their key feedback if you missed them in person.

Nowadays consultants often see patients and order tests and medications in the EMR without speaking to the requesting attending physician. It may take days for their notes or dictation to show up in the electronic medical record, and depending on the complexity of the system, they may be nearly impossible to find. The result is redundant phone calling (asking the consultant’s admin, NP, PA etc. if they know if he’s seen the patient and what the plan is), and sometimes missed steps in the timely ordering of tests and procedures. At times I simply resort to asking the patient if Dr. So-And-So has stopped by, and if they know what he was planning to do. This doesn’t inspire confidence on the patient’s part, I can tell you.

4. I could order anything I wanted. EMR order entry systems force you to select from drop down menus that may not reflect your intentions. When you have a pen and paper – imagine this – you can very clearly and accurately capture what you’d like to order for the patient! There is no confusion about drug taper schedules, wound care instructions, weight bearing status, exercise precautions. It’s all as clear as free text. You can even explain why substitutes are not acceptable, thus heading off a follow up pharmacist call.

5. The patient became the focus. Since I didn’t need to spend all my time entering data into a computer system in real time, I was able to focus more carefully and clearly on the patients. My attention was not constantly being distracted by EMR alerts, unimportant drug interaction warnings, or forced entry of irrelevant information in order to complete a task. I felt more relaxed, I had more time to think, and I got more important work done.

In conclusion, it is obvious to me that we have a long way to go in making EMRs fit our natural pre-zombification hospital workflow. At the very least, we should be developing the following tools:

1. We need better ways to separate the signal from the noise. Even something as simple as a different font color for the new information that we doctors enter (in a given progress note) would help the eye latch on to what’s important. There should be a simple, visual way to distinguish between template and free text.

2. We need a pen feature that allows authors to signify emphasis. Wouldn’t it be nice if there could be an overlay that allowed us to circle words or add arrows or underlines? If the TV weather man can do this on his digital map, why can’t EMRs allow this layer? For example, physicians would like to circle lab values that are changing, and indicate the direction of change.

3. We need boxes where we can draw diagrams. A simple tablet function would be easy enough to enable. Sure it would be nice to have a stylus, but I’d settle for mouse or track pad entry. This is not a feature of most EMRs I’ve used, but could easily become one. Perhaps not everyone will want to use this feature, but for the artistic among us, it would be a god-send.

4. We need a Four-Square check in type feature so that physicians immediately know if their patient has been seen by the requested consultants. Their impressions should be quickly accessible (perhaps with a voice text to the ordering MD) while their formal consultation notes are grinding their way through the system days later.

5. We need to pare down the unnecessary EMR alerts, and off load data entry required to meet billing requirements to non-clinical staff. Physicians need to focus on their patient care, not spin their wheels figuring out coding subtleties and CMS documentation requirements that could be completed by others.

6. We need more flexibility in data order entry – so that treatment intentions are captured, not forced into an ill-fitting box. Currently, physicians are finding ways to free text their orders in bizarre “work arounds” just to get them on the record somewhere. This is a recipe for disaster, as lost orders are fairly commonplace when staff aren’t on the same page regarding where to look for free text orders. I feel badly for the nurses, since “note to nurse” seems to be the favored way to enter a complicated pharmacy order.

I am grateful that I got one last look at hospital care as it used to be – so that I can put my finger on why our new digital system is not working well. I just hope that my suggestions help to make processes better for all of us medical zombies in the new digital world.

***

More advice for EMR Vendors here.

Pluses and minuses of EMRs.

Many of the patients that I treat have brain injuries. Whether caused by a stroke, car accident, fall, or drug overdose, their rehab course has taught me one thing: nobody likes to be forced to do things against their will. Even the most devastated brains seem to remain dimly aware of their loss of independence and buck against it. Sadly, the hospital environment is designed for staff convenience, not patient autonomy.

Many of the patients that I treat have brain injuries. Whether caused by a stroke, car accident, fall, or drug overdose, their rehab course has taught me one thing: nobody likes to be forced to do things against their will. Even the most devastated brains seem to remain dimly aware of their loss of independence and buck against it. Sadly, the hospital environment is designed for staff convenience, not patient autonomy.

In the course of one of my recent days, I witnessed a few patient-staff exchanges that sent me a clear message. First was a young man with a severe brain injury who was admitted from an outside hospital. EMS had placed him in a straight jacket to control his behavior on his trip and by the time I met him, he was in a total panic. Sweating, thrashing, at risk for self harm. He didn’t have the ability to understand fully what was happening but one thing he knew – he was being restrained against his will. The staff rushed to give him a large dose of intramuscular Ativan, but I had a feeling that he would calm down naturally if we got him into a quiet room with dim lights and a mattress with wall padding set up on the floor. As it turned out, the environmental intervention was much more successful than the medicine. Within minutes of being freed to move as he liked, he stopped moving much at all.

Later I was speaking with one of my patients in the shared dining room. An aide arrived with a terry cloth bib to tie around his neck so that he didn’t spill anything during lunch. I saw a flash of anger in my patient’s eyes as he pulled the bib away from his neck with his good arm and placed the towel on his lap instead. I could tell that he found the bib infantalizing, though none of us had thought twice about it before. Here again, a patient did not appreciate having everything determined for him, right down to napkin placement.

Towards the end of the day, I was bidding farewell to a patient whose care would be provided by another attending physician going forward. I was summarizing my view of his progress and expectations for the future, and stopped to ask if he had any questions. What he asked completely flummoxed me. Instead of probing for details about his medical condition and treatment options, he asked, “Will the new doctor be a good listener? Will she pay attention to what I’m saying and be easy to talk to?”

It is unfortunate that healthcare providers and patients are often on very different wavelengths. In Atul Gawande’s recent book, Being Mortal, he argues that nursing homes have often failed to provide healthy environments for patients because they have focused exclusively on safety and meeting basic needs (eating, dressing, bathing, etc.) on their terms. The removal of patient independence unwittingly results in devastating loneliness, helplessness, and depression. It seems to me that hospitals end up doing the same thing to patients – if only for a shorter period of time.

I was moved by Gawande’s book (and I consider it required reading for anyone facing a life-limiting illness or caring for someone who is). It renewed my conviction about the importance of rehabilitation – helping people to become as functionally independent as possible after a devastating injury or disease. Even as we age, we all become less able to do the things we hold dear. Preserving dignity by prolonging independence, and respecting patient autonomy, are often overlooked goals of good health care. It’s time to think about what our actions – even as small as placing a bib around someone’s neck – are doing to our patients’ morale. Maybe it starts with asking the right questions… Or better yet, just watching and listening.

It’s no secret that doctors are disappointed with the way that the U.S. healthcare system is evolving. Most feel helpless about improving their work conditions or solving technical problems in patient care. Fortunately one young medical student was undeterred by the mountain of disappointment carried by his senior clinician mentors…

I am proud to be a part of the American Resident Project an initiative that promotes the writing of medical students residents and new physicians as they explore ideas for transforming American health care delivery. I recently had the opportunity to interview three of the writing fellows about how to…

Book Review: Is Empathy Learned By Faking It Till It’s Real?

I m often asked to do book reviews on my blog and I rarely agree to them. This is because it takes me a long time to read a book and then if I don t enjoy it I figure the author would rather me remain silent than publish my…

The Spirit Of The Place: Samuel Shem’s New Book May Depress You

When I was in medical school I read Samuel Shem s House Of God as a right of passage. At the time I found it to be a cynical yet eerily accurate portrayal of the underbelly of academic medicine. I gained comfort from its gallows humor and it made me…

Eat To Save Your Life: Another Half-True Diet Book

I am hesitant to review diet books because they are so often a tangled mess of fact and fiction. Teasing out their truth from falsehood is about as exhausting as delousing a long-haired elementary school student. However after being approached by the authors’ PR agency with the promise of a…