November 6th, 2014 by Dr. Val Jones in Opinion, Research

No Comments »

I have spent many blog hours bemoaning the inadequate communication going on in hospitals today. Thanks to authors of a new study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, I have more objective data for my ranting. A prospective intervention study conducted at 9 academic children’s hospitals (and involving 10,740 patients over 18 months) revealed that requiring resident physicians to adopt a formal “hand off” process at shift change resulted in a 30% reduction of medical errors.

I have spent many blog hours bemoaning the inadequate communication going on in hospitals today. Thanks to authors of a new study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, I have more objective data for my ranting. A prospective intervention study conducted at 9 academic children’s hospitals (and involving 10,740 patients over 18 months) revealed that requiring resident physicians to adopt a formal “hand off” process at shift change resulted in a 30% reduction of medical errors.

What was the intervention exactly? Details are available via mail order from the folks at Boston Children’s Hospital. It may take me a few weeks to get my hands on the curriculum (which was supported by a grant from the Department of Health and Human Services). I’m not sure how complex the new handoff initiative is in practice (or if it’s something that could be replicated without government-approved formality) but one thing is certain: disciplined physician communication saves lives.

I myself (without a grant from HHS or a NEJM study to back my assertions – ahem) proposed a set of comprehensive communication practices that can help to reduce medical errors in the hospital. My list involves more than peer hand-offs, but also nursing communication, EMR documentation strategies, and reliance on pharmacists for medication reconciliation and review. It is more than just an information exchange protocol for shift-changes, it is a lifestyle choice.

I applaud the I-PASS Handoff Study for its rigorous, evidence-based approach to implementing communication interventions among pediatric residents in children’s hospitals. I am stunned by how effective this one intervention has been – but a part of me is saddened that we practically had to mandate the obvious before it got done. What will it take for physicians to adopt safer communications strategies for inpatient care? I’m guessing that for many of us, it will involve enrollment in a workshop with hospital administration-driven requirements for participation.

For others of us – regular communication with staff, patients, and peers already defines our medical practice. But because (apparently?) we are not in the majority, we’ll just carry on our instinctual carefulness and wait for the rest to catch up. At least now we know that there is a path forward regarding improving communication skills and transfer of patient information. If we have to force doctors to look up from their iPhones and sit around a table and speak to one another – then so be it. The process may improve our lives while it saves those of our patients.

April 21st, 2014 by Dr. Val Jones in Opinion, True Stories

2 Comments »

For the past couple of years I’ve been working as a traveling physician in 13 states across the U.S. I chose to adopt the “locum tenens lifestyle” because I enjoy the challenge of working with diverse teams of peers and patient populations. I believe that this kind of work makes me a better doctor, as I am exposed to the widest possible array of technology, specialist experience, and diagnostic (and logistical) conundrums. During my down times I like to think about what I’ve learned so that I can try to make things better for my next group of patients.

For the past couple of years I’ve been working as a traveling physician in 13 states across the U.S. I chose to adopt the “locum tenens lifestyle” because I enjoy the challenge of working with diverse teams of peers and patient populations. I believe that this kind of work makes me a better doctor, as I am exposed to the widest possible array of technology, specialist experience, and diagnostic (and logistical) conundrums. During my down times I like to think about what I’ve learned so that I can try to make things better for my next group of patients.

This week I’ve been considering how in-patient doctoring has changed since I was in medical school. Unfortunately, my experience is that most of the changes have been for the worse. While we may have a larger variety of treatment options and better diagnostic capabilities, it seems that we have pursued them at the expense of the fundamentals of good patient care. What use is a radio-isotope-tagged red blood cell nuclear scan if we forget to stop giving aspirin to someone with a gastrointestinal bleed?

At the risk of infecting my readers with a feeling of helplessness and depressed mood, I’d like to discuss my findings in a series of blog posts. Today’s post is about why electronic medical charts have become ground zero for deteriorating patient care.

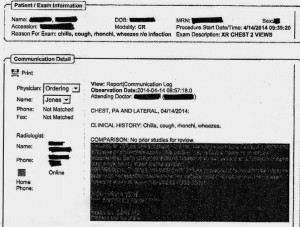

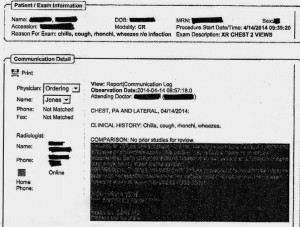

EMR Alert - Featuring radiologist note in illegible font color

1. Medical notes are no longer used for effective communication, but for billing purposes. When I look back at the months of training I received at my alma mater regarding the proper structure of intelligent medical notes, I recall with nostalgia how beautiful they were. Each note was designed to present all the observed and collected data in a cohesive and logical format, justifying the physician’s assessment and treatment plan. Our impressions of the patient’s physical and mental condition, reasons for further testing, and our current thought processes regarding optimal treatments and follow up (including citation of scientific literature to justify the chosen course) were all crisply presented.

Nowadays, medical notes consist of randomly pre-populated check box data lifted from multiple author sources and vomited into a nonsensical monstrosity of a run-on sentence. It’s almost impossible to figure out what the physician makes of the patient or what she is planning to do. Occasional “free text” boxes can provide clues, when the provider has bothered to clarify. One needs to be a medical detective to piece together an assessment and plan these days. It’s both embarrassing and tragic… if you believe that the purpose of medical notes is effective communication. If their purpose is justifying third-party payer requirements, then maybe they are working just fine?

My own notes have been co-opted by the EMRs, so that when I get the chance to free-text some sensible content, it still forces gobbledygook in between. I can see why many of my peers have eventually “given up” on charting properly. No one (except coders and payers interested in denying billing claims) reads the notes anymore. The vicious cycle of unintelligible presentation drives people away from reading notes, and then those who write notes don’t bother to make them intelligent anymore. There is a “learned helplessness” that takes over medical charting. All of this could (I suppose) be forgiven if physicians reverted back to verbal handoffs and updates to other staff/peers caring for patients to solve this grave communication gap. Unfortunately, creating gobbledygook takes so much time that there is less old fashioned verbal communication than ever.

2. No one talks to each other anymore. I’m not sure if this is because of a general cultural shift away from oral communication to text-based, digital intermediaries (think zombie-like teens texting one another incessantly) or if it’s related to sheer time constraints. However, I am continually astonished by the lack of face-to-face or verbal communication going on in hospitals these days. When I first observed this phenomenon, I attributed it to the facility where I was working. However, experience has shown that this is an endemic problem in the entire healthcare system.

When you are overworked, it’s natural to take the path of least resistance – checking boxes and ordering consults in the EMR is easier than picking up a phone and constructing a coherent patient presentation to provide context for the specialist who is about to weigh in on disease management. Nursing orders are easier to enter into a computer system than actually walking over and explaining to him/her what you intend for the patient and why.

But these shortcuts do not save time in the long run. When a consultant is unfamiliar with the partial workup you’ve already completed, he will start from the beginning, with duplicate testing and all its associated expenses, risks, and rabbit trails. When a nurse doesn’t know that you’ve just changed the patient to “NPO” status (or for what reason) she may give him/her scheduled medications before noticing the change. When you haven’t explained to the physical therapists why it could be dangerous to get a patient out of bed due to a suspected DVT, the patient could die of a sudden pulmonary embolism. Depending upon computer screen updates for rapid changes in patient care plans is risky business. EMRs are poor substitutes for face-to-face communication.

In one case I remember a radiology tech expressing amazement that I had bothered to type the reason for the x-ray in the order field. How can a radiologist be expected to rule out something effectively if he isn’t given the faintest hint about what he’s looking for? On another occasion I called to speak with the radiologist on a complicated case where the patient’s medical history provided him with a clue to look for something he hadn’t thought of – and his re-read of the CT scan led to the discovery and treatment of a life-threatening disease. Imagine that? An actual conversation saved a life.

3. It’s easy to be mindless with electronic orders. There’s something about the brain that can easily slip into “idle” mode when presented with pages of check boxes rather than a blank field requiring original input. I cannot count the number of times that I’ve received patients (from outside hospitals) with orders to continue medications that should have been stopped (or forgotten medications that were not on the list to be continued). In one case, for example, a patient with a very recent gastrointestinal bleed had aspirin listed in his current medication list. In another, the discharging physician forgot to list the antibiotic orders, and the patient had a partially-treated, life-threatening infection.

As I was copying the orders on these patients, I almost made the same mistakes. I was clicking through boxes in the pharmacy’s medication reconciliation records and accidentally approved continuation of aspirin (which I fortunately caught in time to cancel). It’s extremely unlikely that I would have hand-written an order for aspirin if I were handling the admission in the “old fashioned” paper-based manner. My brain had slipped into idle… my vigilance was compromised by the process.

In my view, the only communication problem that EMRs have solved is illegible handwriting. But trading poor handwriting for nonsensical digital vomit isn’t much of an advance. As far as streamlining orders and documentation is concerned, yes – ordering medications, tests, and procedures is much faster. But this speed doesn’t improve patient care any more than increasing the driving speed limit from 60 mph to 90 mph would reduce car accidents. Rapid ordering leads to more errors as physicians no longer need to think carefully about everything. EMRs have sped up processes that need to be slow, and slowed down processes that need to be fast. From a clinical utility perspective, they are doing more harm than good.

As far as coding and billing are concerned, I suppose they are revolutionary. If hospital care is about getting paid quickly and efficiently then perhaps we’re making great strides? But if we are expecting EMRs to facilitate care quality and communication, we’re in for a big disappointment. EMRs should have remained a back end billing tool, rather than the hub of all hospital activity. It’s like using Quicken as your life’s default browser. Over-reach of this particular technology is harming our patients, undermining communication, and eroding critical thinking skills. Call me Don Quixote – but I’m going to continue tilting at the hospital EMR* windmill (until they are right-sized) and engage in daily face-to-face meetings with my peers and hospital care team.

*Note: there is at least one excellent, private practice EMR (called MD-HQ). It is for use in the outpatient setting, and is designed for communication (not billing). It is being adopted by direct primary care practices and was created by physicians for supporting actual thinking and relevant information capture. I highly recommend it!

March 24th, 2014 by Dr. Val Jones in Health Policy, Health Tips, Opinion

3 Comments »

One of my biggest pet peeves is taking over the care of a floor-full of complicated patients without any explanation of their current conditions or plan of care from the physician who most recently treated them. Absent or inadequate verbal and written “handoffs” of patient care are alarmingly common in my experience. I work primarily as a locum tenens physician, traveling across the country to “cover” for my peers on vacation or when hospitals are having a hard time recruiting a full-time MD. This type of work is particularly vulnerable to gaps in continuity of care, and has heightened my awareness of the prevalence of poor sign-outs.

One of my biggest pet peeves is taking over the care of a floor-full of complicated patients without any explanation of their current conditions or plan of care from the physician who most recently treated them. Absent or inadequate verbal and written “handoffs” of patient care are alarmingly common in my experience. I work primarily as a locum tenens physician, traveling across the country to “cover” for my peers on vacation or when hospitals are having a hard time recruiting a full-time MD. This type of work is particularly vulnerable to gaps in continuity of care, and has heightened my awareness of the prevalence of poor sign-outs.

Recent research suggests that communications lapses are the number one cause of medical errors and adverse events in the healthcare system. An analysis published in the Archives of Internal Medicine suggests various kinds of consequences stemming from inadequate transfer of information, including missed diagnoses, incomplete work ups, ICU admissions, and near-miss errors. I have personally witnessed all manner of problems, including medication errors (the patient’s full list of medical conditions was not known by the new physician), lack of follow up for incidental (though life-threatening) findings discovered during a hospital stay, progression of infection due to treatment delay, inappropriate antibiotic therapy (follow up review of bacterial drug resistance results did not occur), accidental repeat fluid boluses in patients who no longer required rehydration (and had kidney or heart failure), etc.

It has long been suspected, though not unequivocally proven, that sleep deprivation (due to extended work hours and long shifts) is a common cause of medical errors. New regulations limiting resident physician work hours to 80 hours a week have substantially improved the quality of life for MDs in training, but have not made a remarkable difference in medical error rates. In my opinion, this is because sleep deprivation is a smaller contributor to the error problem than incomplete information transfer. If we want to keep our patients safe, we need to do a better job of transferring clinical information to peers assuming responsibility for patient care. This requires more than checklists (made popular by Atul Gawande et al.), it’s about creating a culture of carefulness.

Over the past few decades, continuity of care has been undermined by a new “shift worker” or “team” approach. Very few primary care physicians admit patients to local hospitals and continue to manage their care as inpatients. Instead, hospitalists are responsible for the medical management of the patient – often sharing responsibility as a group. This results in reduced personal knowledge of the patient, leading to accidental oversights and errors. The modern shift-worker model is unlikely to change, and with the rise of locum tenens physicians added to the mix – it’s as if hospitalized patients are chronically cared for by “float staff,” seeing the patient for the very first time each day.

As a physician frustrated with the dangers of chronically poor sign-outs, these are the steps that I take to reduce the risk of harm to my patients:

1. Attend nursing change of shift as much as possible. Some of the most accurate and best clinical information about patients may be obtained from those closest to them. Nurses spend more face-to-face time with patients than any other staff members and their reports to one another can help to nip problems in the bud. I often hear things like, “I noticed that Mr. Smith’s urine was cloudy and smelled bad this morning.” Or “Mrs. Jones complained of some chest pain overnight but it seems to be better now after the Percocet.” These bits of information might not be relayed to the physician until they escalate into fevers, myocardial infarctions, or worse. In an effort to not “bother the physician with too much detail” nurses often unwittingly neglect to share subtle findings that can prevent disease progression. If you are new to a unit or don’t already know the nursing staff well, join their morning or evening sign out meeting(s). They (and you) will be glad you did.

2. Pretend that every new patient needs an H&P (complete history and physical exam). When I pick up a new patient, I comb through their medical chart very thoroughly and carefully. I only need to do this once, and although it takes time, it saves a lot of hassle in the long run. I make note of every problem they’ve had (over the years and currently) and list them in a systems-based review that I refer to in every note I write thereafter.

3. Apply the “trust but verify” principle. I read other physicians’ notes with a careful eye. Electronic medical records systems are notorious for “copy and paste” errors and accidentally carrying over “old news” as if it were an active problem. If a physician notes that the patient has a test or study pending, I’ll search for its result. If they are being treated empirically for some kind of infection, I will look for microbiologic evidence that the bug is sensitive to the antibiotics they are receiving. I’ll ask the patient if they’ve had their radiology study yet, and then search for the result. I’ll review the active medication list and see if one of my peers discontinued or started a new medicine without letting me know. I never assume that anything in the medical record is correct. I try my best to double check the notes and data.

4. Create a systems-based plan of care, reconcile it each day with the active medication list. I like to organize patient diseases and conditions by body systems (e.g. cardiovascular, endocrine, gastrointestinal, neurologic, dermatologic, etc.) and list all the diseases/conditions and medications currently being offered to treat them. This only has to be done thoroughly one time, and then updated and edited with additional progress notes. This helps all consultants and specialists focus in on their particular area of interest and know immediately what is currently being done for the patient (both in their system of interest and as a whole) with a glance at your note. Since medications often have multiple purposes, it is also very helpful to see the condition being treated by each medication. For example, if the patient is on coumadin, is it because they have a history of atrial fibrillation, a prosthetic heart valve, a recent orthopedic procedure, or something else? That can easily be gleaned from a note with a systems-based plan of care.

5. Confirm your assessment and plan with your patient. I often review my patients’ medication and problem list with them (at least once) to ensure that they are aware of all of their diagnoses, and to make sure I haven’t missed anything. Sometimes a patient will have a condition (otherwise unmentioned in their record) that they treat with certain medications at home that they are not getting in the hospital. Errors of omission are not uncommon.

6. Sign out face-to-face or via phone whenever possible. These days people seem to be less and less eager to engage with each other face-to-face. Texting, emailing, and written sign-outs often substitute for face-to-face encounters. I try to remain “old school” about sign-outs because inevitably, something important comes up during the conversation that isn’t noted in the paper record. Things like, “Oh, and Mr. Smith tried to hit the nursing staff last night but he seems calmer now.” That’s something I want to know about so I can preempt new episodes, right nursing staff?

7. Create a culture of carefulness. As uncomfortable as it is to confront peers who may not be as enthusiastic about detailed sign-outs as I am, I still take the initiative to get information from them when I come on service and make sure that I call them to provide them with a verbal sign-out when I’m leaving my patients in their hands. By modeling good sign offs, and demonstrating their utility by heading off problems at the pass, I find that other doctors generally appreciate the head’s up, and slowly adopt some of my strategies (at least when working with me). I have found that nurses are particularly good at learning to tell me everything (no matter how small it may seem at the time) and have heard time and again that things “just run so much more smoothly” when we communicate and even “over-communicate” when in doubt.

“The Devil is in the details.” This is more true at your local hospital than almost anywhere else. Reducing hospital error rates is possible with some good, old-fashioned verbal handoffs and a small dose of charting OCD. Let’s create a culture of carefulness, physicians, so we don’t get crushed with more top-down bureaucratic rules to solve this problem. We can fix this ourselves, I promise.

January 6th, 2012 by Toni Brayer, M.D. in Research

1 Comment »

It’s time for some good news! A study that looked at online patient ratings about their physicians from 2004 through 2010 showed that the average physician rating was 9.3 out of 10. That is amazingly high and shows that patients (at least the ones who posted on Dr.Score) are very content with the care they receive from their doctor. Even though some patients will post a nasty comment about the doctor, the overall patient satisfaction is high. Seventy percent of doctors earned a perfect 10.

It’s time for some good news! A study that looked at online patient ratings about their physicians from 2004 through 2010 showed that the average physician rating was 9.3 out of 10. That is amazingly high and shows that patients (at least the ones who posted on Dr.Score) are very content with the care they receive from their doctor. Even though some patients will post a nasty comment about the doctor, the overall patient satisfaction is high. Seventy percent of doctors earned a perfect 10.

The survey asked patients to Read more »

*This blog post was originally published at EverythingHealth*

December 19th, 2011 by Bryan Vartabedian, M.D. in Opinion

No Comments »

Let’s say you’re a doctor and you have an idea, opinion, or a new way of doing things. What do you do with it?

Let’s say you’re a doctor and you have an idea, opinion, or a new way of doing things. What do you do with it?

It used to be that the only place we could share ideas was in a medical journal or from the podium of a national meeting. Both require that your idea pass through someone’s filter. As physicians we’ve been raised to seek approval before approaching the microphone.

This is unfortunate. When I think about the doctors around me, I think about the remarkable mindshare that exists. Each is unique in the way they think. Each sees disease and the human condition differently. But for many their brilliance and wisdom is stored away deep inside. They are human silos of unique experience and perspective. They are of a generation when someone else decided if their ideas were worthy of discussion. They are of a generation when it was understood that few ideas are worthy of discussion. They are the medical generation of information isolation.

I spoke with a couple of students recently about Read more »

*This blog post was originally published at 33 Charts*

I have spent many blog hours bemoaning the inadequate communication going on in hospitals today. Thanks to authors of a new study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, I have more objective data for my ranting. A prospective intervention study conducted at 9 academic children’s hospitals (and involving 10,740 patients over 18 months) revealed that requiring resident physicians to adopt a formal “hand off” process at shift change resulted in a 30% reduction of medical errors.

I have spent many blog hours bemoaning the inadequate communication going on in hospitals today. Thanks to authors of a new study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, I have more objective data for my ranting. A prospective intervention study conducted at 9 academic children’s hospitals (and involving 10,740 patients over 18 months) revealed that requiring resident physicians to adopt a formal “hand off” process at shift change resulted in a 30% reduction of medical errors.

For the past couple of years I’ve been working as a traveling physician in 13 states across the U.S. I chose to adopt the “

For the past couple of years I’ve been working as a traveling physician in 13 states across the U.S. I chose to adopt the “

One of my biggest pet peeves is taking over the care of a floor-full of complicated patients without any explanation of their current conditions or plan of care from the physician who most recently treated them. Absent or inadequate verbal and written “handoffs” of patient care are alarmingly common in my experience. I work primarily as a

One of my biggest pet peeves is taking over the care of a floor-full of complicated patients without any explanation of their current conditions or plan of care from the physician who most recently treated them. Absent or inadequate verbal and written “handoffs” of patient care are alarmingly common in my experience. I work primarily as a