April 22nd, 2014 by Dr. Val Jones in Health Policy, Humor, Opinion

1 Comment »

In my last post I wrote about the communication difficulties caused by electronic medical records systems. The response on Twitter ranged from sentiments including everything from “right on, sister” to “greedy doctors are only complaining about EMRs because of their price tag.” The disconnect between policy wonk’s (and EMR vendor’s) belief in the transformative power of EMRs and exasperated clinician users of these products is jaw-dropping. Physicians are often labeled as obstinate dinosaurs, blocking progress, while policy wonks are considered by physicians to be living in an alternate reality where a mobile phone app could fix all that is wrong with the healthcare system.

In my last post I wrote about the communication difficulties caused by electronic medical records systems. The response on Twitter ranged from sentiments including everything from “right on, sister” to “greedy doctors are only complaining about EMRs because of their price tag.” The disconnect between policy wonk’s (and EMR vendor’s) belief in the transformative power of EMRs and exasperated clinician users of these products is jaw-dropping. Physicians are often labeled as obstinate dinosaurs, blocking progress, while policy wonks are considered by physicians to be living in an alternate reality where a mobile phone app could fix all that is wrong with the healthcare system.

Being on the dinosaur side, I thought I’d try a quick experiment/analogy to demonstrate that EMR dissatisfaction is not a mere cost artifact. To show what happens when a digital intermediary runs medical information through a translator, I selected a random paragraph about the epidemiology of aphasias from an article in Medscape. I copied and pasted it into Google translator and then ran it backwards and forwards a few times in different languages. In the end, the original paragraph (exhibit A) became the second paragraph (exhibit B):

Exhibit A:

“Not enough data are available to evaluate differences in the incidence and clinical features of aphasia in men and women. Some studies suggest a lower incidence of aphasia in women because they may have more bilaterality of language function. Differences may also exist in aphasia type, with more women than men developing Wernicke aphasia.”

Exhibit B:

“Prevalence and characteristics of men and women are expected to afasia is not enough information available. If afasia some studies, women work more, not less, because they show that the spoken language. There may be differences in the type of OST, women and men to develop more of a vernikke afasia, more.”

Although the B paragraph bears some resemblance to A, it is nearly impossible to determine its original meaning. This is similar to what happens to medical notes in most current EMRs (except the paragraph would be broken up with lab values and vital signs from the past week or two). If your job were to read hundreds of pages of B-type paragraphs all day, what do you think would happen? Would you enthusiastically adopt this new technology? Or would you give up reading the notes completely? Would you need to spend hours of your day finding “work-arounds” to correct the paragraphs?

And what would you say if the government mandated that you use this new technology or face decreased reimbursement for treating patients? What if you needed to demonstrate “meaningful use” or dependency and integration of the translator into your daily workflow in order to keep your business afloat? What if the scope of the technology were continually expanded to include more and more written information so that everything from lab orders to medication lists to hospital discharges, nursing summaries, and physical therapy notes, etc. were legally required to go through the translator first? And if you pointed out that this was not improving communication but rather introducing new errors, harming patients, and stealing countless hours from direct clinical care, you would be called “change resistant” or “lazy.”

And what if 68,000 new medical codes were added to the translator, so that you couldn’t advance from paragraph to paragraph without selecting the correct code for a disease (such as gout) without reviewing 150 sub-type versions of the code. And then what if you were denied payment for treating a patient with gout because you did not select the correct code within the 150 subtypes? And then multiply that problem by every condition of every patient you ever see.

Clearly, the cost of the EMR is the main reason why physicians are not willing to adopt them without complaint. Good riddance to the 50% of doctors who say they’re going to quit, retire, or reduce their work hours within the next three years. Without physicians to slow down the process of EMR adoption, we could really solve this healthcare crisis. Just add on a few mobile health apps and presto: we will finally have the quality, affordable, healthcare that Americans deserve.

April 21st, 2014 by Dr. Val Jones in Opinion, True Stories

2 Comments »

For the past couple of years I’ve been working as a traveling physician in 13 states across the U.S. I chose to adopt the “locum tenens lifestyle” because I enjoy the challenge of working with diverse teams of peers and patient populations. I believe that this kind of work makes me a better doctor, as I am exposed to the widest possible array of technology, specialist experience, and diagnostic (and logistical) conundrums. During my down times I like to think about what I’ve learned so that I can try to make things better for my next group of patients.

For the past couple of years I’ve been working as a traveling physician in 13 states across the U.S. I chose to adopt the “locum tenens lifestyle” because I enjoy the challenge of working with diverse teams of peers and patient populations. I believe that this kind of work makes me a better doctor, as I am exposed to the widest possible array of technology, specialist experience, and diagnostic (and logistical) conundrums. During my down times I like to think about what I’ve learned so that I can try to make things better for my next group of patients.

This week I’ve been considering how in-patient doctoring has changed since I was in medical school. Unfortunately, my experience is that most of the changes have been for the worse. While we may have a larger variety of treatment options and better diagnostic capabilities, it seems that we have pursued them at the expense of the fundamentals of good patient care. What use is a radio-isotope-tagged red blood cell nuclear scan if we forget to stop giving aspirin to someone with a gastrointestinal bleed?

At the risk of infecting my readers with a feeling of helplessness and depressed mood, I’d like to discuss my findings in a series of blog posts. Today’s post is about why electronic medical charts have become ground zero for deteriorating patient care.

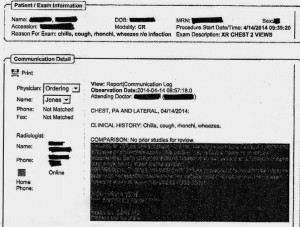

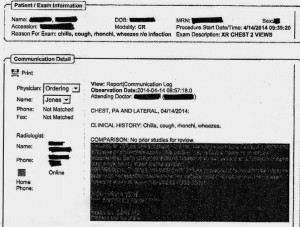

EMR Alert - Featuring radiologist note in illegible font color

1. Medical notes are no longer used for effective communication, but for billing purposes. When I look back at the months of training I received at my alma mater regarding the proper structure of intelligent medical notes, I recall with nostalgia how beautiful they were. Each note was designed to present all the observed and collected data in a cohesive and logical format, justifying the physician’s assessment and treatment plan. Our impressions of the patient’s physical and mental condition, reasons for further testing, and our current thought processes regarding optimal treatments and follow up (including citation of scientific literature to justify the chosen course) were all crisply presented.

Nowadays, medical notes consist of randomly pre-populated check box data lifted from multiple author sources and vomited into a nonsensical monstrosity of a run-on sentence. It’s almost impossible to figure out what the physician makes of the patient or what she is planning to do. Occasional “free text” boxes can provide clues, when the provider has bothered to clarify. One needs to be a medical detective to piece together an assessment and plan these days. It’s both embarrassing and tragic… if you believe that the purpose of medical notes is effective communication. If their purpose is justifying third-party payer requirements, then maybe they are working just fine?

My own notes have been co-opted by the EMRs, so that when I get the chance to free-text some sensible content, it still forces gobbledygook in between. I can see why many of my peers have eventually “given up” on charting properly. No one (except coders and payers interested in denying billing claims) reads the notes anymore. The vicious cycle of unintelligible presentation drives people away from reading notes, and then those who write notes don’t bother to make them intelligent anymore. There is a “learned helplessness” that takes over medical charting. All of this could (I suppose) be forgiven if physicians reverted back to verbal handoffs and updates to other staff/peers caring for patients to solve this grave communication gap. Unfortunately, creating gobbledygook takes so much time that there is less old fashioned verbal communication than ever.

2. No one talks to each other anymore. I’m not sure if this is because of a general cultural shift away from oral communication to text-based, digital intermediaries (think zombie-like teens texting one another incessantly) or if it’s related to sheer time constraints. However, I am continually astonished by the lack of face-to-face or verbal communication going on in hospitals these days. When I first observed this phenomenon, I attributed it to the facility where I was working. However, experience has shown that this is an endemic problem in the entire healthcare system.

When you are overworked, it’s natural to take the path of least resistance – checking boxes and ordering consults in the EMR is easier than picking up a phone and constructing a coherent patient presentation to provide context for the specialist who is about to weigh in on disease management. Nursing orders are easier to enter into a computer system than actually walking over and explaining to him/her what you intend for the patient and why.

But these shortcuts do not save time in the long run. When a consultant is unfamiliar with the partial workup you’ve already completed, he will start from the beginning, with duplicate testing and all its associated expenses, risks, and rabbit trails. When a nurse doesn’t know that you’ve just changed the patient to “NPO” status (or for what reason) she may give him/her scheduled medications before noticing the change. When you haven’t explained to the physical therapists why it could be dangerous to get a patient out of bed due to a suspected DVT, the patient could die of a sudden pulmonary embolism. Depending upon computer screen updates for rapid changes in patient care plans is risky business. EMRs are poor substitutes for face-to-face communication.

In one case I remember a radiology tech expressing amazement that I had bothered to type the reason for the x-ray in the order field. How can a radiologist be expected to rule out something effectively if he isn’t given the faintest hint about what he’s looking for? On another occasion I called to speak with the radiologist on a complicated case where the patient’s medical history provided him with a clue to look for something he hadn’t thought of – and his re-read of the CT scan led to the discovery and treatment of a life-threatening disease. Imagine that? An actual conversation saved a life.

3. It’s easy to be mindless with electronic orders. There’s something about the brain that can easily slip into “idle” mode when presented with pages of check boxes rather than a blank field requiring original input. I cannot count the number of times that I’ve received patients (from outside hospitals) with orders to continue medications that should have been stopped (or forgotten medications that were not on the list to be continued). In one case, for example, a patient with a very recent gastrointestinal bleed had aspirin listed in his current medication list. In another, the discharging physician forgot to list the antibiotic orders, and the patient had a partially-treated, life-threatening infection.

As I was copying the orders on these patients, I almost made the same mistakes. I was clicking through boxes in the pharmacy’s medication reconciliation records and accidentally approved continuation of aspirin (which I fortunately caught in time to cancel). It’s extremely unlikely that I would have hand-written an order for aspirin if I were handling the admission in the “old fashioned” paper-based manner. My brain had slipped into idle… my vigilance was compromised by the process.

In my view, the only communication problem that EMRs have solved is illegible handwriting. But trading poor handwriting for nonsensical digital vomit isn’t much of an advance. As far as streamlining orders and documentation is concerned, yes – ordering medications, tests, and procedures is much faster. But this speed doesn’t improve patient care any more than increasing the driving speed limit from 60 mph to 90 mph would reduce car accidents. Rapid ordering leads to more errors as physicians no longer need to think carefully about everything. EMRs have sped up processes that need to be slow, and slowed down processes that need to be fast. From a clinical utility perspective, they are doing more harm than good.

As far as coding and billing are concerned, I suppose they are revolutionary. If hospital care is about getting paid quickly and efficiently then perhaps we’re making great strides? But if we are expecting EMRs to facilitate care quality and communication, we’re in for a big disappointment. EMRs should have remained a back end billing tool, rather than the hub of all hospital activity. It’s like using Quicken as your life’s default browser. Over-reach of this particular technology is harming our patients, undermining communication, and eroding critical thinking skills. Call me Don Quixote – but I’m going to continue tilting at the hospital EMR* windmill (until they are right-sized) and engage in daily face-to-face meetings with my peers and hospital care team.

*Note: there is at least one excellent, private practice EMR (called MD-HQ). It is for use in the outpatient setting, and is designed for communication (not billing). It is being adopted by direct primary care practices and was created by physicians for supporting actual thinking and relevant information capture. I highly recommend it!

In my last post I wrote about the communication difficulties caused by electronic medical records systems. The response on Twitter ranged from sentiments including everything from “right on, sister” to “greedy doctors are only complaining about EMRs because of their price tag.” The disconnect between policy wonk’s (and EMR vendor’s) belief in the transformative power of EMRs and exasperated clinician users of these products is jaw-dropping. Physicians are often labeled as obstinate dinosaurs, blocking progress, while policy wonks are considered by physicians to be living in an alternate reality where a mobile phone app could fix all that is wrong with the healthcare system.

In my last post I wrote about the communication difficulties caused by electronic medical records systems. The response on Twitter ranged from sentiments including everything from “right on, sister” to “greedy doctors are only complaining about EMRs because of their price tag.” The disconnect between policy wonk’s (and EMR vendor’s) belief in the transformative power of EMRs and exasperated clinician users of these products is jaw-dropping. Physicians are often labeled as obstinate dinosaurs, blocking progress, while policy wonks are considered by physicians to be living in an alternate reality where a mobile phone app could fix all that is wrong with the healthcare system.

For the past couple of years I’ve been working as a traveling physician in 13 states across the U.S. I chose to adopt the “

For the past couple of years I’ve been working as a traveling physician in 13 states across the U.S. I chose to adopt the “