May 29th, 2014 by Dr. Val Jones in Health Policy, Opinion

4 Comments »

In an effort to save on human resources costs, some hospitals have decided to make locum tenens* doctors and nurses line items in a supply list. Next to IV tubing, liquid nutritional supplements and anti-bacterial wipes you’ll find slots for nurses, surgeons, and hospitalist positions. This depressing commoditization of professional staffing is a new trend in healthcare promoted by software companies promising to solve staffing shortages with vendor management systems (VMS). In reality, they are removing the careful provider recruiting process from job matching, causing a “race to the bottom” in care quality. Instead of filling a staff position with the most qualified candidates with a proven track record of excellent bedside manner and evidence-based practice, physicians and nurses with the lowest salary requirements are simply booked for work.

In an effort to save on human resources costs, some hospitals have decided to make locum tenens* doctors and nurses line items in a supply list. Next to IV tubing, liquid nutritional supplements and anti-bacterial wipes you’ll find slots for nurses, surgeons, and hospitalist positions. This depressing commoditization of professional staffing is a new trend in healthcare promoted by software companies promising to solve staffing shortages with vendor management systems (VMS). In reality, they are removing the careful provider recruiting process from job matching, causing a “race to the bottom” in care quality. Instead of filling a staff position with the most qualified candidates with a proven track record of excellent bedside manner and evidence-based practice, physicians and nurses with the lowest salary requirements are simply booked for work.

In a policy environment where quality measures and patient satisfaction ratings are becoming the basis for reimbursement rates, one wonders how VMS software is getting traction. Perhaps desperate times call for desperate measures, and the challenge of filling employment gaps is driving interest in impersonal digital match services? Rural hospitals are desperate to recruit quality candidates, and with a severe physician shortage looming, warm bodies are becoming an acceptable solution to staffing needs.

As distasteful as the thought of computer-matching physicians to hospitals may be, the real problems of VMS systems only become apparent with experience. After discussing user experience with several hospital system employees and reading various blogs and online debates here’s what I discovered:

1. Garbage In, Garbage Out. The people who input physician data (including their certifications, medical malpractice histories, and licensing data) have no incentive to insure accuracy of information. Head hunter agencies are paid when the physicians/nurses they enter into the database are matched to a hospital. To make sure that their providers get first dibs, they may leave out information, misrepresent availability, and in extreme cases, even falsify certification statuses. These errors are often caught during the hospital credentialing process, which results in many hours of wasted time on the part of internal credentialing personnel, and delays in filling the position. In other cases, the errors are not caught during credentialing and legal problems ensue when impaired providers are hired accidentally.

2. Limitation of choice. The non-compete contracts associated with VMS systems typically prevent hospital physician recruiters from contacting staffing agencies directly to fill their needs. This forces the hospital to rely on the database for all staffing leads. At least 68% of staffing agencies do not participate with VMS systems, so a large portion of the most carefully vetted professionals remain outside the VMS, inaccessible to those who contracted to use it.

3. Extra hospital employee training required. There are hundreds of proprietary VMS systems in use. Each one requires specialized training to manage everything from durable medical equipment to short term surgical staff. In cases where hospital staff are spread too thin to master this training, some VMS companies are pleased to provide a “managed service provider” or MSP to outsource the entire recruitment process. This adds additional layers, further removing the hospital recruiter from the physician.

4. Providers hate VMS systems. As anyone who has read a recent nursing blog can attest, VMS systems are universally despised by the potential employees they represent. VMS paints professionals in black and white, without the ability to distinguish quality, personality, or perform careful reference checks. They force down salaries, may rule out candidates based on where they live (travel costs), and provide no opportunity to negotiate salary vis-a-vis work load. When a hospital opts to use a VMS system as a middle man between them and the staffing agencies, the agencies often pass along the cost to the providers by offering them a lower hourly rate.

5. Provider privacy may be compromised. Once a physician or nurse curriculum vitae (CV) is entered into the VMS database the agency recruiter who entered it has 1 year (I can’t confirm that this is true for all systems) to represent them exclusively. After that, the CV is often available for any recruiter who has access to that VMS to view or pitch to any client. There is a wide variety of agency quality in the healthcare staffing industry, with some being highly ethical and selective in choosing their clients (only quality hospitals) and providers (carefully screened). Others are transactional, bottom-feeders with all the scruples of a used car salesman. When your data is in a VMS, one minute you might be represented by a caring, thoughtful recruiter who understands and respects your career needs, and the next (without your informed consent) you’ll be matched to a bankrupt hospital undergoing investigation by the Department of Health by a gum-chewing salesman who threatens you with a lawsuit if you don’t complete an assignment for half the pay you usually receive.

6. No cost savings, only increased liability. In the end, some hospitals who have tried VMS systems say that their decreased hiring costs have not resulted in overall savings. While they may see a downward shift in salary paid to their temporary work force, they get what they pay for. Just one “bad hire” who causes a medical malpractice lawsuit can eat up salary savings for an entire year of VMS. Not to mention the increased costs associated with a slower hiring process, attrition from poor fits, and the inconvenience of having to re-recruit for positions over and over again. Providers also lose out on career opportunities while they’re “on hold” during a prolonged hiring process. And for those who layer on a MSP, they lose control of the most important hospital quality and safety line of defense – choosing your own doctors and nurses.

In summary, while the idea of using a software matching service for recruiting physicians and nurses to hospitals sounds appealing at first, the bottom line is that reducing care providers to a group of numerical fields removes all the critical nuance from the hiring process. VMS, with their burdensome non-competes, cumbersome technology, and lack of quality control are an unwelcome new middle man in the healthcare staffing environment. It is my hope that they will be squeezed out of the business based on their own inability to provide value to a healthcare system that craves and rewards quality and excellence in its staff.

Job matching requires thoughtful hospital recruiters in partnership with ethical, experienced agencies. Choosing one’s hospital gauze vendor should involve a different selection algorithm than hiring a new chief of surgery. It’s time for physician and nurse groups to take a stand against this VMS-inspired commoditization of medicine before its roots sink in too deeply and we all become mere line items on a hospital vendor list. So next time you doctors and nurses plan to work a temporary assignment, ask your recruiter if they use a VMS system. Avoiding those agencies who do may mean a much better (and higher paying) work experience.

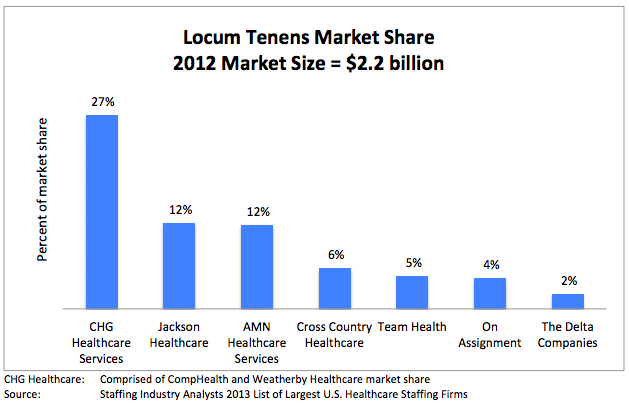

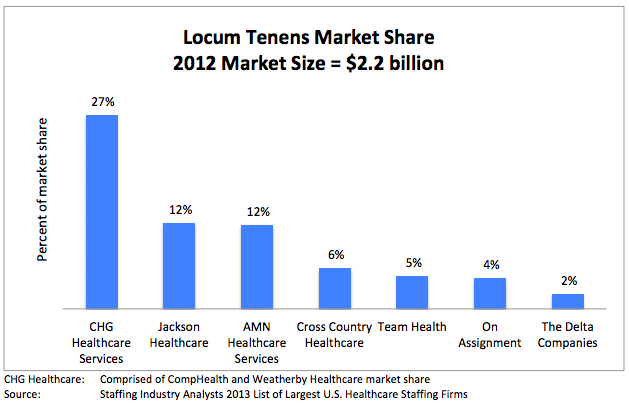

*Locum tenens (filling hospital staffing needs with part time or traveling physicians and nurses) is big business. Here is a run down of the estimated market size and its key industry leaders (provided by CompHealth):

May 5th, 2014 by Dr. Val Jones in Expert Interviews, Health Policy, Opinion

1 Comment »

It’s no secret that most physicians are unhappy with the way things are going in healthcare. Surveys report high levels of job dissatisfaction, “burn out” and even suicide. In fact, some believe that up to a third of the US physician work force is planning to leave the profession in the next 3 years – an alarming statistic.

It’s no secret that most physicians are unhappy with the way things are going in healthcare. Surveys report high levels of job dissatisfaction, “burn out” and even suicide. In fact, some believe that up to a third of the US physician work force is planning to leave the profession in the next 3 years – an alarming statistic.

Direct primary care practices are touted as the best way to restore patient and provider satisfaction. Those brave enough to cut out the “middle man” (i.e. health insurers, both public and private) find a remarkable reduction in billing paperwork, unrecovered fees, and electronic documentation requirements. I know many physicians who have made the switch and are extremely happy to be able to spend most of their time in direct patient care, unfettered by most rules, regulations, and coding systems. They can solve problems via phone, email, text, video chat, or in-office as the need arises without having to worry about whether or not their manner of interaction will be reimbursed.

Direct primary care is probably the best way to find freedom and happiness in practicing outpatient medicine. But where does that leave physicians who are tied to hospital care due to the nature of their specialty (surgeons, intensivists, anesthesiologists, etc.)? Is there any way for them to find a brighter way forward?

I have found that working as a locum tenens hospital-based physician has dramatically improved my work satisfaction, and it may do so for you too. Here’s why:

1. You can take as much time off as you want, anytime you want. Do not underestimate the power of frequent vacations on your mental health. The frenetic pace of the hospital is much more tolerable in short doses. My attitude, stamina, and ability to stay focused is dramatically improved by working only 2-3 week stretches at a time. When I feel good, I can spread the cheerfulness, and I am happy to spend longer hours at work to give my patients more of my time.

2. You can avoid most political drama. Hospitals are incredibly stressful environments filled with hierarchical and territorial land mines. Being a short-timer allows you to avoid many conflicts. Administrators never nag you, or hold you responsible for perceived departmental deficiencies. You don’t need to attend committee meetings or become involved in personality quirk arbitrage. You can stay above the fray, focusing purely on the patients.

3. You learn all kinds of new things. Exposure to different patient populations, hospital expertise and different peer groups exposes you to a broader swath of technology and humanity. No longer will you be tied to the regional practice idiosyncrasies of a single hospital – you’ll learn how to tackle problems from many different angles. That knowledge earns you respect, and serves to cross-pollinate your own specialty, making you – and those you learn from – better doctors.

4. You are free to leave. There’s something refreshing about knowing that you can leave a place that you don’t like without any repercussions. No matter how unpleasant a locums assignment, it will end, and you can saunter off to brighter pastures.

5. You make more money. Believe it or not, locums work can be quite lucrative if you find the right assignments. I know a team of hospitalists who travel the country together, negotiating higher rates since they are a “one stop” solution. Their housing, travel, and cars are paid for by the agency, and they have take home pay (before taxes) around $350K per year. I personally think that working that many hours as a locum tenens physician kind of defeats the purpose of avoiding burn out, but some people like to do it that way.

6. You can live in the warm states in the winter, and the cold ones in the summer. Enough said.

7. You can try before you buy. Maybe you’re not sure where you want to sink down career roots. Or maybe you’re not sure you’ll like living in a certain city or part of the world? Maybe your family isn’t sure they want to move to a new location? Locum tenens assignments are the perfect way to try before you buy.

8. You can use your experience to become an excellent consultant. With long term exposure to various hospital systems, you are in a unique position to develop an encyclopedic knowledge of best practices. Sharing how other hospitals have solved their challenges can spark reform at other institutions. You can become a real force for positive change, not just on a micro level, but system and state-wide.

Working as a locum tenens physician may enhance your career satisfaction and promote professional advancement. What it will not solve, however, is the following:

1. You still have to work within the framework of bureaucracy endemic to hospitals. You’ll need to learn to use multiple different EMR systems and fill out most of the same paperwork that you do as a full-timer. This is painful at first, but once you’ve mastered the most common EMR systems (I’ve only really encountered 5 different ones in 2 years of locum tenens work) you’ll find a clinical rhythm that fits into most frameworks.

2. You will be living out of a suitcase. If the disruption of frequent travel is too much for you (or your family) to bear, then perhaps the locums lifestyle is not for you.

3. You will be annoyed by the process of getting multiple medical licenses and hospital credentialing. Agencies try to help with this burden, but mostly, you’ll need to suffer through this part yourself.

4. You will have to live with some degree of uncertainty. Part of the nature of working as a locum tenens physician is that clients (hospitals) change their minds frequently. They try to fill open positions with local staff or hire additional full-timers, using locums as their more expensive back ups. Assignments fall through frequently, so you’ll need to be ready to change course quickly.

Overall, I believe that locum tenens work can provide the practice freedom that many hospital-based physicians crave. If you’re eager to get off the unrelenting clinical treadmill, this is an easy way to do it. At a recent assignment near New Hampshire, I mused at the license plates that I passed on my way to work: “Live free or die” is their state motto. And I think it captures my sentiments exactly.

March 24th, 2014 by Dr. Val Jones in Health Policy, Health Tips, Opinion

3 Comments »

One of my biggest pet peeves is taking over the care of a floor-full of complicated patients without any explanation of their current conditions or plan of care from the physician who most recently treated them. Absent or inadequate verbal and written “handoffs” of patient care are alarmingly common in my experience. I work primarily as a locum tenens physician, traveling across the country to “cover” for my peers on vacation or when hospitals are having a hard time recruiting a full-time MD. This type of work is particularly vulnerable to gaps in continuity of care, and has heightened my awareness of the prevalence of poor sign-outs.

One of my biggest pet peeves is taking over the care of a floor-full of complicated patients without any explanation of their current conditions or plan of care from the physician who most recently treated them. Absent or inadequate verbal and written “handoffs” of patient care are alarmingly common in my experience. I work primarily as a locum tenens physician, traveling across the country to “cover” for my peers on vacation or when hospitals are having a hard time recruiting a full-time MD. This type of work is particularly vulnerable to gaps in continuity of care, and has heightened my awareness of the prevalence of poor sign-outs.

Recent research suggests that communications lapses are the number one cause of medical errors and adverse events in the healthcare system. An analysis published in the Archives of Internal Medicine suggests various kinds of consequences stemming from inadequate transfer of information, including missed diagnoses, incomplete work ups, ICU admissions, and near-miss errors. I have personally witnessed all manner of problems, including medication errors (the patient’s full list of medical conditions was not known by the new physician), lack of follow up for incidental (though life-threatening) findings discovered during a hospital stay, progression of infection due to treatment delay, inappropriate antibiotic therapy (follow up review of bacterial drug resistance results did not occur), accidental repeat fluid boluses in patients who no longer required rehydration (and had kidney or heart failure), etc.

It has long been suspected, though not unequivocally proven, that sleep deprivation (due to extended work hours and long shifts) is a common cause of medical errors. New regulations limiting resident physician work hours to 80 hours a week have substantially improved the quality of life for MDs in training, but have not made a remarkable difference in medical error rates. In my opinion, this is because sleep deprivation is a smaller contributor to the error problem than incomplete information transfer. If we want to keep our patients safe, we need to do a better job of transferring clinical information to peers assuming responsibility for patient care. This requires more than checklists (made popular by Atul Gawande et al.), it’s about creating a culture of carefulness.

Over the past few decades, continuity of care has been undermined by a new “shift worker” or “team” approach. Very few primary care physicians admit patients to local hospitals and continue to manage their care as inpatients. Instead, hospitalists are responsible for the medical management of the patient – often sharing responsibility as a group. This results in reduced personal knowledge of the patient, leading to accidental oversights and errors. The modern shift-worker model is unlikely to change, and with the rise of locum tenens physicians added to the mix – it’s as if hospitalized patients are chronically cared for by “float staff,” seeing the patient for the very first time each day.

As a physician frustrated with the dangers of chronically poor sign-outs, these are the steps that I take to reduce the risk of harm to my patients:

1. Attend nursing change of shift as much as possible. Some of the most accurate and best clinical information about patients may be obtained from those closest to them. Nurses spend more face-to-face time with patients than any other staff members and their reports to one another can help to nip problems in the bud. I often hear things like, “I noticed that Mr. Smith’s urine was cloudy and smelled bad this morning.” Or “Mrs. Jones complained of some chest pain overnight but it seems to be better now after the Percocet.” These bits of information might not be relayed to the physician until they escalate into fevers, myocardial infarctions, or worse. In an effort to not “bother the physician with too much detail” nurses often unwittingly neglect to share subtle findings that can prevent disease progression. If you are new to a unit or don’t already know the nursing staff well, join their morning or evening sign out meeting(s). They (and you) will be glad you did.

2. Pretend that every new patient needs an H&P (complete history and physical exam). When I pick up a new patient, I comb through their medical chart very thoroughly and carefully. I only need to do this once, and although it takes time, it saves a lot of hassle in the long run. I make note of every problem they’ve had (over the years and currently) and list them in a systems-based review that I refer to in every note I write thereafter.

3. Apply the “trust but verify” principle. I read other physicians’ notes with a careful eye. Electronic medical records systems are notorious for “copy and paste” errors and accidentally carrying over “old news” as if it were an active problem. If a physician notes that the patient has a test or study pending, I’ll search for its result. If they are being treated empirically for some kind of infection, I will look for microbiologic evidence that the bug is sensitive to the antibiotics they are receiving. I’ll ask the patient if they’ve had their radiology study yet, and then search for the result. I’ll review the active medication list and see if one of my peers discontinued or started a new medicine without letting me know. I never assume that anything in the medical record is correct. I try my best to double check the notes and data.

4. Create a systems-based plan of care, reconcile it each day with the active medication list. I like to organize patient diseases and conditions by body systems (e.g. cardiovascular, endocrine, gastrointestinal, neurologic, dermatologic, etc.) and list all the diseases/conditions and medications currently being offered to treat them. This only has to be done thoroughly one time, and then updated and edited with additional progress notes. This helps all consultants and specialists focus in on their particular area of interest and know immediately what is currently being done for the patient (both in their system of interest and as a whole) with a glance at your note. Since medications often have multiple purposes, it is also very helpful to see the condition being treated by each medication. For example, if the patient is on coumadin, is it because they have a history of atrial fibrillation, a prosthetic heart valve, a recent orthopedic procedure, or something else? That can easily be gleaned from a note with a systems-based plan of care.

5. Confirm your assessment and plan with your patient. I often review my patients’ medication and problem list with them (at least once) to ensure that they are aware of all of their diagnoses, and to make sure I haven’t missed anything. Sometimes a patient will have a condition (otherwise unmentioned in their record) that they treat with certain medications at home that they are not getting in the hospital. Errors of omission are not uncommon.

6. Sign out face-to-face or via phone whenever possible. These days people seem to be less and less eager to engage with each other face-to-face. Texting, emailing, and written sign-outs often substitute for face-to-face encounters. I try to remain “old school” about sign-outs because inevitably, something important comes up during the conversation that isn’t noted in the paper record. Things like, “Oh, and Mr. Smith tried to hit the nursing staff last night but he seems calmer now.” That’s something I want to know about so I can preempt new episodes, right nursing staff?

7. Create a culture of carefulness. As uncomfortable as it is to confront peers who may not be as enthusiastic about detailed sign-outs as I am, I still take the initiative to get information from them when I come on service and make sure that I call them to provide them with a verbal sign-out when I’m leaving my patients in their hands. By modeling good sign offs, and demonstrating their utility by heading off problems at the pass, I find that other doctors generally appreciate the head’s up, and slowly adopt some of my strategies (at least when working with me). I have found that nurses are particularly good at learning to tell me everything (no matter how small it may seem at the time) and have heard time and again that things “just run so much more smoothly” when we communicate and even “over-communicate” when in doubt.

“The Devil is in the details.” This is more true at your local hospital than almost anywhere else. Reducing hospital error rates is possible with some good, old-fashioned verbal handoffs and a small dose of charting OCD. Let’s create a culture of carefulness, physicians, so we don’t get crushed with more top-down bureaucratic rules to solve this problem. We can fix this ourselves, I promise.

October 15th, 2013 by Dr. Val Jones in Expert Interviews

No Comments »

I recently wrote about my experiences as a traveling physician and how to navigate locum tenens work. Today I want to talk about the client (in this case, hospital) side of the equation. I’ve had the chance to speak with several executives (some were physicians themselves) about the overall process of hiring and managing temporary physicians. What I heard wasn’t pretty. I thought I’d summarize their opinions in the form of a mock composite interview to protect their anonymity – I’m hoping that locum MDs and agencies alike can learn from this very candid discussion.

I recently wrote about my experiences as a traveling physician and how to navigate locum tenens work. Today I want to talk about the client (in this case, hospital) side of the equation. I’ve had the chance to speak with several executives (some were physicians themselves) about the overall process of hiring and managing temporary physicians. What I heard wasn’t pretty. I thought I’d summarize their opinions in the form of a mock composite interview to protect their anonymity – I’m hoping that locum MDs and agencies alike can learn from this very candid discussion.

Dr. Val: How do you feel about Locum Tenens agencies?

Executive: They’re a necessary evil. We are desperate to fill vacancies and they find doctors for us. But they know we are desperate and they take full advantage of that.

Dr. Val: What do you mean?

Executive: They charge very high hourly rates, and they don’t care about finding the right fit for the job. They seem to have no interest in matching physician temperament with hospital culture. They are only interested in billable hours and warm bodies, unfortunately. But we know this going in.

Dr. Val: Do you try to screen the candidates yourself before they begin work at your hospital?

Executive: Yes, we carefully review all their CVs and we interview them over the phone.

Dr. Val: So does that help with finding better matches?

Executive: Not really. Everyone looks good on paper and they sound competent on the phone. You only really know what their work ethic is like once they’ve started seeing patients.

Dr. Val: What percent of locums physicians would you say are “sub-par” then?

Executive: About 50%.

Dr. Val: Whoah! That’s very high. What specifically is wrong with them? Are they poor clinicians or what?

Executive: It’s a lot of things. Some are poor clinicians, but more commonly they just don’t work very hard. They have this attitude that they only have to see “X” number of patients per day, no matter what the census. So they’re not good team players. Also many of them have prima donna attitudes. They just swish into our hospital and tell us how they like to do things. They have no problem complaining or calling out flaws in the system because they know they can walk away and never see us again.

Dr. Val: Yikes, they sound horrible. Looking back on those interviews that you did with them, could you see any of this coming? Are there red flags in retrospect?

Executive: None that I can think of. All of our problem locums have been very different – some are old, some are young – they come from very different backgrounds, cultures, and parts of the country. I can’t think of anything they had in common on paper or in the phone interviews.

Dr. Val: So maybe the agencies don’t screen them well?

Executive: Right. I think they probably ignore negative feedback about a physician and just “solve the problem” by not sending them back to the same hospital. They just send them elsewhere – and so the problem continues. They have no incentive really to take a locums physician out of circulation unless they do something truly dangerous at work (medical malpractice). That’s pretty rare.

Dr. Val: I recently wrote on my blog that there are 4 kinds of physicians who do locums: 1. Retirees, 2. Salary Seekers, 3. Dabblers and 4. Problem personalities – would you agree with those categories?

Executive: Yes, but I think that a large proportion of the locums I’ve met have been either motivated by money (i.e. they want to make some extra cash so they can go on a fancy vacation) or they just don’t get along well with others. There are more “problem people” out there than you think.

Dr. Val: This is rather depressing. Have you found that some agencies do a better job than others at keeping the “good” physicians coming?

Executive: Well, we only work with 2 or 3 agencies, so I can’t speak to the entire range of options. We just can’t handle the complexity associated with juggling too many recruiters at once because we end up with accidental overlap in contracts. We have booked two doctors via two different agencies for the same block of time and then we are legally bound to take them both. It’s an expensive mistake.

Dr. Val: Does one particular agency stand out to you in terms of quality of experience?

Executive: No. Actually they all seem about the same.

Dr. Val: For us locums doctors, I can tell you that agencies vary quite a bit in terms of quality of assignments and general process.

Executive: There may be a difference on your end, but not much on ours.

Dr. Val: So, being that using locums has been a fairly negative experience for you, what do you intend to do to change it?

Executive: We are trying very hard to recruit full time physicians to join our staff so that we reduce our need for locums docs. It’s not easy. Full time physician work has become, quite frankly, drudgery. Our system is so burdened with bureaucratic red tape, decreasing reimbursement, billing rules and government regulations that it sucks the soul right out of you. I don’t like who I become when I work full time. That’s why I had to take an administrative job. I still see patients part-time, but I can also get the mental and emotional break I need.

Dr. Val: So you’re actually a functional locums yourself, if not a literal one.

Executive: Yes, that’s right. I have some guilt about not working full time, and yet, I have to maintain my sanity.

Dr. Val: Given the generally negative work environment that physicians live in these days, I suppose that temporary work is only going to increase exponentially as others take the path that you and I have chosen?

Executive: With the looming physician shortage, rural centers in particular are going to have to rely more and more on locums agencies. What agencies really need to do to distinguish themselves is hire clinicians to help them screen and match locums to hospitals. Agencies don’t seem to really understand what we need or what the problems are with their people. If they had medical directors or a chief medical officer, people who have worked in the trenches and understand both the client side and the locum side, they would be much better at screening candidates and meeting our needs. Until then, we’re probably going to have to limp along with a 50% miss-match rate.

August 11th, 2013 by Dr. Val Jones in Opinion, True Stories

No Comments »

On Assignment In California Vineyard

This post is the continuation of my personal thoughts and reflections about what it’s like to work as a Locum Tenens (traveling temp) physician.

Q: Where are the most favorable locums jobs?

This is an interesting question and depends a little bit upon personal taste and priorities. While most locums physicians choose their work based on location (see this nice survey of locum priorities), more experienced locums docs choose their work based on circumstance. What I mean is that it’s more important WHY the hospital needs you, than where the hospital is physically located. It only takes one really bad assignment to learn that lesson the hard way. For instance, if a hospital is recruiting a locum tenens physician because the place is so bad that no one will stay in the job, then I can pretty much guarantee that it won’t matter how nice the city/town/countryside is nearby, you will not enjoy your time there.

Positive prognostic indicators for a good locums assignment include:

1. The person you’re filling in for needs vacation coverage or are on maternity/paternity leave. They are happy with their job and are eager to come back.

2. The hospital is undergoing a growth phase and needs help staffing new wings/wards.

3. The hospital is operating in the black but happens to be in a rural area where it is challenging to find enough physicians to meet the patient needs.

Red flags:

1. The medical director/staff physician “doesn’t have time” to talk to you about the assignment before you commit to doing it.

2. There is more than a second-long pause when you ask the medical director why he/she would want to work there as a locums.

3. The person you’re filling in for was fired due to incompetence or negligence.

4. The person you’re filling in for is on the verge of a nervous break down from overwork, and a locums agency was called in to prevent implosion/explosion type scenarios.

5. There have been multiple staff (nursing usually) strikes at the hospital in the past 6 months.

7. The group with whom you would work is not culturally diverse – and you can imagine having difficulty gaining acceptance by them.

In my experience, you can enjoy living anywhere temporarily if the people and circumstances are pleasant. A nice post-work dinner/coffee with friendly, competent staff – even in a “backwater” setting – trumps a solo trip to a high end, big city restaurant when you are emotionally and mentally exhausted by the misery of a bad hospital. Trust me on this.

As one locums hospitalist put it: “Generally I’ve found the rural hospitals to be the nicest, especially in the midwest. But I’m never going back to South Dakota in the winter.”

Q: How can I negotiate the best salary?

First of all, you need to know that this is a negotiation. When I first started, I just assumed the salary I was offered required a binary response: “Yes, I’ll accept the position,” or “No I’ll keep looking for other opportunities.” That’s why I’m a physician and not a business woman, I guess! Just ask my husband.

Anyway, after a few experiences of getting paid a lower salary than my peers at the same job, I realized the error of my ways. In many cases you can lobby for up to 25% higher pay rate, so you should keep that in mind. In summary, here is where the salary “wiggle room” is:

1. How much overhead your agency charges. Remember the “platinum” agency I referred to in my last post? If you’re working with one of the agencies that is known to be “expensive” then they have more money that they could share with you. If you’re working with a budget agency who competes based on low overhead fees (such as 20% above your base salary rate), then you’ll never get more than $5-10 more/hour from them.

2. If you have a good track record. Once you’ve proven yourself to be an excellent physician, well-liked by the hospital staff where you’ve been assigned, the agency is going to want to keep sending you to new assignments because you’re more likely to get requests to return and will stay longer at each gig. The agency (and the recruiters) make money based on how many hours you bill, so they’d rather send a “sure thing” to a new client than an unknown. They will be more likely to up your salary to seal the deal, knowing they’ll probably get more hours with you in the long run.

3. How desperate the client/hospital is. This is sad to say, but desperate clients will pay higher rates to fill a need. If you’re being offered an unusually high salary for a certain assignment, don’t rejoice, worry (see notes above about “red flags.”)

4. If you bundle. Some enterprising primary care locums docs get together to negotiate group rates. That means, if you have a friend or two who can agree to travel together to a particular place, the agency can pay a higher salary to each of you because they’re getting a larger volume of hours overall. This works really well for internal medicine locums, for example, where hospitals often need multiple docs at a time. It’s actually a brilliant plan, because the people who do it are already sympatico, they have similar work ethics, can share call, sign out to each other, have built in friends to enjoy after work adventures, and arrive as a well-oiled machine. I think this is probably the future of primary care locums. However, if you’re like me (a specialist in a small field) there’s no way to bundle because no hospital ever needs more than one of you at a time. 😉

5. If you take longer assignments. This stands to reason. If you are going to be working for months (rather than weeks) at a certain hospital, then you have more room to negotiate a larger hourly rate based on the volume principle I described above.

Q: How do locums agencies decide how to match you with a given job opportunity?

Based on my experience, the agencies’ order of priorities for matching physicians with clients are:

1. Whoever is available and answers their phone first. The Locums world is very dog-eat-dog for the agencies. It’s a daily race to see who can present physicians to fill needs the fastest. Hospitals are looking for the lowest cost solution to their staffing gaps, and will shop multiple agencies for the same positions at once. The agency who brings the first acceptable C.V.s wins the work. Sometimes when there is controversy over which agency gets the job, the client has to review email time/date stamps to verify which came first. Sometimes it’s a matter of minutes. So… if your recruiter’s voice sounds a little tense, you’ll understand what’s going on in his/her world. And if you’re hungry for locums work, be sure to respond promptly for consideration. That being said, once you’ve established a track record with a few agencies, you’ll have turn away business year-round (especially in primary care).

2. Client preference. Once your C.V. has been presented to the client, they will choose their preferred candidate (if there is more than one option). Usually, they are looking for someone local or whomever will generate the lowest travel expenses. I wish that clients delved a little deeper than that, but my experience is that cost trumps coolness for them most of the time. And when I say “coolness” I mean – wouldn’t you rather have a candidate who writes well, has an unusual background (say – someone who has built medical websites and has been a food critic and cartoonist? Ahem?) than just another chem major straight out of IM residency? Apparently most would say no thanks. Just give me the cheaper one.

3. If they know and like you. Let’s say there are two equally qualified physicians for the same position already screened and signed up for work at a certain agency. If one of you has a track record of being flexible and easy to work with (rather than a demanding, entitled brat – like a few doctors you may know) then the recruiter will put the “nice” person’s CV on top and market you more strongly to the client. Why? Because she doesn’t want to receive whiny phone calls every other day during your assignment about how you don’t like the hospital food. The recruiters have “quality of life” issues too. If you’re lucky and you develop a good, long term relationship with your recruiter, they’ll probably even do YOU a favor and give you a head’s up about upcoming opportunities at the “good” hospitals. And we all know what that means.

4. Whoever will take the lowest hourly rate. In the end, it’s still all about the Benjamins so if there are 2 equally qualified physicians who are similarly “non whiny” then if one will work more days or at a lower rate, then they are more likely to get the job (due to recruiter influence on client preference). But given the large number of positions and the small number of locums to choose from, this game is 80% about who’s available first. Then the rest of the variables follow.

Q: What is the licensing and credentialing process like? How do I make it easier?

The state licensing and hospital credentialing is the most painful administrative part of the whole locum tenens assignment process. If you’re considering an opportunity in say, North Dakota, then you’ll need to get a state license there (Unless you already have one?) as well as passing the scrutiny of the rural hospital credentialing committee where you’ll be working. And yes, everyone seems to want original copies of the intern year you did 15 years ago at the hospital that has since closed. You feel my pain?

There is good news and bad news about this. The good news is that the Locums agencies have hired staff to complete the medical license and credentialing paperwork for you. That is part of the “value” they bring to you as an agency. The bad news is that some of their staff can’t spell. Or they get the chronological order of your residency/fellowship years wrong, etc. thus generating MORE work for you in the long run, correcting errors rather than filling in blanks.

The middle road is to fill out the paperwork correctly yourself the first time, and then offer copies to the agency staff for future licensure/credentialing. They can transcribe better than synthesize, so this seems to be the best way to go, IMO.

Hospital credentialing is nuanced, and depends on the culture of the local hospital in terms of how many references they require and how much documentation detail they request. Some hospitals are swift and lean, others comb through your background as if you are a likely convicted felon.

That being said, one thing is certain – if you plan to work several different locums assignments your referrers are going to be nagged TO DEATH. Everyone needs 2-3 professional references who will be called/contacted mercilessly, first by the Locums agency to make sure you’re not a “problem person” (as described in Part 1), then by the hospital who is considering hiring you (not that they’ve committed yet), then by the credentialing committee (if you pass approval in the first round), then by the state licensing body. So for every potential locums assignment, your professional reference will likely be contacted 4 times, and asked to vouch for you verbally or on paper/via fax. Imagine how many assignments you’ll do in a year and the math gets pretty scary. Be sure your references are ok with all this attention… and give them fair warning. If you can, spread the pain and broaden your reference base.

Q. What advice do you have for Locums agencies?

1. Physicians talk. Whatever sneaky deal-making you’re doing (such as paying people different rates for the same gig or getting a 50% premium at a desperate hospital and then not sharing it with us in salary upgrade) is going to come to light at some point, so keep your nose clean. Please be honest about problem hospitals and work conditions. I know that clients mislead you about work conditions and expectations so as to lure locums to their facility – but try to go the extra mile to figure out in advance if the doctors are really going to be asked to see 16 patients a day or 26 patients a day. Because if we get to the site and we’re being abused and overworked, we associate the negative experience with the agency that put us there. Then you try to wheedle and cajole us into finishing the assignment based on the contract we signed so you can make your cut. Meanwhile we’re putting our careers in danger because we can’t do a thorough job and might miss something important. Not good for physician retention. Better yet, just say no to crisis clients. The money isn’t worth it.

2. Treat us right and you’ll make more money in the long run. I know you’re under pressure to save money on our travel and hotels, but you also have some flexibility in the room rate that you’ll consider. Put us in a nicer hotel for a few bucks extra per night and the whole experience will seem a little brighter. Put us on the preferred rental car program so we don’t have to wait for 2 hours in a rental car line after a full day of cross-country travel. Upgrade us to a full size car rather than the beige Corolla we have to live in for months. These little things end up costing you only a few hours of our total billing, but make your agency our go-to employer.

3. Pay us on time. It’s so simple, and costs you nothing. If an agency takes 3-4 months to pay me for an assignment, and then the billing is inaccurate (missing hours)… I’m going to choose another agency next time. Your value to me is partly in the ease of payment – a direct deposit a week from when I fax my time sheets sends me the message that you have your act together and are respectful of my time. Making me sift through miss-billed records from half a year ago is just not acceptable.

4. Try to understand why we whine. Locums work is not easy. We are often separated from our friends and family, in an unfamiliar setting, learning complicated hospital processes with patients who are sick and dying. We don’t know if the nurses or consultants are competent while we ourselves are under intense scrutiny until the staff gets to know us. We have to build trust, navigate complicated electronic medical records systems, satisfy hospital coding and billing demands, and keep a ward full of patients (with their team of specialists whom we’ve yet to meet) on the path to healing. All this, and we are legally responsible for everything that goes on in the lives of those under our care. When we get home to our Days Inn at the end of our 15 hour shift in our beige Toyota Corolla to find their exercise equipment broken and the lobby overrun with monster-truck rally participants, we may be a tad whiny. Please don’t think ill of us for that. Just do what you can to help us feel better. We, and our patients, will thank you.

***

Dr. Jones is available on a consulting basis through Better Health LLC. She may be reached at val.jones@getbetterhealth.com

In an effort to save on human resources costs, some hospitals have decided to make locum tenens* doctors and nurses line items in a supply list. Next to IV tubing, liquid nutritional supplements and anti-bacterial wipes you’ll find slots for nurses, surgeons, and hospitalist positions. This depressing commoditization of professional staffing is a new trend in healthcare promoted by software companies promising to solve staffing shortages with vendor management systems (VMS). In reality, they are removing the careful provider recruiting process from job matching, causing a “race to the bottom” in care quality. Instead of filling a staff position with the most qualified candidates with a proven track record of excellent bedside manner and evidence-based practice, physicians and nurses with the lowest salary requirements are simply booked for work.

In an effort to save on human resources costs, some hospitals have decided to make locum tenens* doctors and nurses line items in a supply list. Next to IV tubing, liquid nutritional supplements and anti-bacterial wipes you’ll find slots for nurses, surgeons, and hospitalist positions. This depressing commoditization of professional staffing is a new trend in healthcare promoted by software companies promising to solve staffing shortages with vendor management systems (VMS). In reality, they are removing the careful provider recruiting process from job matching, causing a “race to the bottom” in care quality. Instead of filling a staff position with the most qualified candidates with a proven track record of excellent bedside manner and evidence-based practice, physicians and nurses with the lowest salary requirements are simply booked for work.

It’s no secret that most

It’s no secret that most  One of my biggest pet peeves is taking over the care of a floor-full of complicated patients without any explanation of their current conditions or plan of care from the physician who most recently treated them. Absent or inadequate verbal and written “handoffs” of patient care are alarmingly common in my experience. I work primarily as a

One of my biggest pet peeves is taking over the care of a floor-full of complicated patients without any explanation of their current conditions or plan of care from the physician who most recently treated them. Absent or inadequate verbal and written “handoffs” of patient care are alarmingly common in my experience. I work primarily as a  I recently wrote about

I recently wrote about