August 19th, 2009 by Toni Brayer, M.D. in Better Health Network, Opinion, True Stories

No Comments »

Dear President Obama,

I am in favor of Health Care Reform and I agree with you that universal coverage and eliminating the abuses that both patients and doctors have suffered at the whim of the for-profit insurance industry must be curtailed.

But I also want you to fix Medicare. Medicare is so bureaucratic that expanding it in its current form would be the death knell for primary care physicians and many community hospitals. The arcane methods of reimbursement, the ever expanding diagnosis codes, the excessive documentation rules and the poor payment to “cognitive, diagnosing, talking” physicians makes the idea of expansion untenable.

May I give you one small example, Mr. President? I moved my medical office in April. Six weeks before the move I notified Medicare of my pending change of address and filled out 22 pages of forms. Yes, Mr. Commander in Chief…22 pages for a change of address. It is now mid-August and I still do not have the “approval” for my address change.

I continue to care for my Medicare patients and they are a handful. Older folks have quite a number of medical issues, you see, and sometimes it takes 1/2 hour just to go over their medications and try to understand how their condition has changed. That is before I even begin to examine them and explain tests, treatment and coordinate their care. Despite the fact that I care for these patients, according the Medicare rules, I cannot submit a bill to Medicare because they have not approved my change of office address.

I have spent countless hours on the phone with Medicare and have sent additional documentation that they requested. I send the forms and information “overnight, registered” because a documented trail is needed to avoid having to start over at the beginning again and again. I was even required to send a signature from my “bank officer” and a utility bill from the office. Mr President, I don’t have a close relationship with a bank officer so this required a bank visit and took time away from caring for patients…but I certainly did comply.

I am still waiting to hear from Medicare. At my last call they said they had not received yet another document, but when I gave them the post office tracking number, they said it was received after all. They could not tell me when or if they will accept my address change.

I have bills stacking up since April and I just found out that they will not accept them if they are over 30 days old. I have cared for patients for 5 months and will not receive any reimbursement from Medicare. The rules state I cannot bill the patient or their supplemental Medicare insurance either.

Believe me, Mr. President, I commend you for taking on such a huge task. Please also know that Medicare reform is needed along with health care reform.

A loyal American ,

Internal Medicine (aka: primary care) physician

*This blog post was originally published at EverythingHealth*

July 22nd, 2009 by Happy Hospitalist in Better Health Network, Health Policy, Primary Care Wednesdays

No Comments »

What does that mean? Well. It means everything. And it means nothing. It is the enormous universe of numbered codes (CPT) that every physician must grasp in order to get paid for services provided. In order to remain a viable business, physicians must learn how to code. And they must learn how to code well so they aren’t accused of fraud.

The current coding system is ridiculously difficult and vague. So difficult and vague that audits by the Medicare National Bank (MNB) often result in multiple different opinions by the MNB auditors themselves.

Coding is a system of confusion. I am here to say the coding system is insane. Current coding rules are used by all third parties to determine the economic value of your care. To determine how much your encounter with the patient is worth. Ultimately, the coding system has become the most important aspect of a physician’s professional life because coding determines revenue. And revenue determines the viability of the business model. And that ultimately determines how much you take home to feed your family. Dr Kevin blogged about that here.

So let the games begin. The current coding rules are a futile attempt to bring rings of value to medical service. Services which are so vastly different and unique for every patient. I will attempt to walk you through an example of the payment system, and how it relates to relative value units (RVUs) and ultimately how that affects physician payment.

The number of codes is massive. For all imaginable procedures, encounters, surgeries. Any possible health care interaction. Hospitalist medicine is limited in the types of codes we use. So I only have to remember a few.

95% of my billing is based on about twenty CPT codes:

3 Admit codes (99221,99222,99223)

3 follow up codes.(99231,99232,99233)

2 critical care codes (99291, 99292)

5 consult codes (99251-99255)

7 observation codes (99218-99220, 99234-99236, 99217)

2 Discharge codes (99238, 99239)

There are a few others, but these twenty-two codes determine my very financial existence. Medicare says so. Imagine a surgeon, a primary care doc, and a medical subspecialist. Every single interaction has a code. There are codes for codes, modifiers for codes, add on codes, disallowed codes, V codes, M codes. It seems as if the list is endless. And you have to get it right. Every time. Or you don’t get paid. Or you are accused of fraud. It is an impossible feat. The process of taking care of patients has turned into a game of documentation. And that has drastically affected the efficiency of the practice of medicine.

Let me walk you through a 99223, the code for the highest level admit for inpatient care. A level three. There is no actual law, as I understand it, on the Medicare books that definitely defines the requirement for these Evaluation and Management (E&M) codes. There are generally accepted guidelines which carriers are expected to follow. 1995 and 1997 guidelines. Even the guidelines from different years are different. And you are allowed to pick and chose from both. More silliness.

The following is my understanding of what Medicare requires in order to bill a level three admit, CPT code 99223. You must have every one of these components or it’s considered fraud, over-billing or waste. Pick your verbal poison.

1) History of Present Illness (HPI) : This requires four elements (character, onset, location, duration, what makes it better or worse, associated signs and symptoms) or the status of three chronic medical conditions.

2) Past Medical History (PMH): This requires a complete history of medical (medical problems, allergies, medications), family (what does your family suffer from), social (do you smoke or shoot up cocaine?) histories.

3) Review of Systems (ROS): A 12 point review of systems which asks you every possible question in the book. Separated by organ system.

4) Complete Physical Exam (PE): With components of all organ systems, the rules of which are highly complex in and of itself.

5) High Complexity Medical Decision-Making: This one is great. It is broken down into three areas and you must have 2 of 3 components as follows; Pull out your calculator.

5a) Diagnosis. Four points are required to get to high complexity. Each type of problem is defined by a point value (self limiting, established stable, established worsening, new problems with no work up planned and new problems with work up planned). You must know how many points each problem is worth. Count the number of problems. Add up the point value for each problem and you get your point value for Diagnosis (5a). You must have four points to be considered high complexity.

5b) Data. Four points are required for high complexity. Different data components are worth a different number of points. Data includes such things as reviewing or ordering lab, reviewing xrays or EKGs yourself, discussing things with other health care providers (which I have never been able to define), reviewing radiology or nuclear med studies, and obtaining old records etc. Each different data point documented (remember you have to write all this down too) is given a different point value. You must add up the points to determine your level of complexity. Get four points and you get high complexity for Data (5b).

5c) Concepts. I call this the basket. Predefined and sometimes vague medical processes that are defined as high risk. This includes such things as the need to closely monitor drug therapy for signs of toxicity ( I would include sliding scale insulin in this category), de-escalating care, progression or side effect of treatment, severe exacerbation with threat to life or limb, changes in neurological status, acute renal failure and cardiovascular imaging with identified risk factors. There are too many categories that are defined as a high risk concept. I cannot remember all of them. If you have a concept considered high risk, you get credit for high risk in the concepts category (5c)

Now remember, out of 5a, 5b, and 5c, you must meet high high complexity criteria on two out of three to be considered high risk. Did you remember to bring your calculator to work? And once you’ve calculated your high complexity category, don’t forget to write down all the components required from HPI, PMH, ROS, PE to not be accused of fraud.

Folks, this is what I have to document every time I admit a patient to the hospital in order to get paid and not be accused of fraud. This is what the government (and all other subsequent third party systems) have decided is necessary for me to treat you as a patient. This is what I must consider every time I take care of you.

I always find myself wondering if I wrote down that I personally reviewed that EKG. I wonder if I wrote down that your great great grand mother died of “heart problems”. I wonder if I remembered to write down all your pertinent positives on your review of systems and whether I documented the lack of positives in all other systems that were reviewed.

And remember each CPT code is given an RVU value, the value of which is determined by its own three components.

- The work RVU

- The practice expense RVU

- The malpractice expense RVU

Then the MNB multiplies your total RVU (add the three components above) and attached a geographical multiplier (you get more RVUs in NYC than in Montana).

Then, they take that number of RVUs and they multiply it by the Congressional mandated value of the RVU (currently about $35/RVU). That value is currently determined by the political whims of politicians and is controlled by the irrational sustainable growth formula (SGR). That is the formula that is overturned every year because of the irrational economics it employs.

And that’s how a physician is paid. This is what determines whether physicians survive in the business of medicine. And whether they have enough money to pay the electric bill, the accountant’s fees and the matching contribution to their nurse’s 401K.

Oh yeah. I almost forgot, I have to do all this while actually taking care of your medical problems based on sound scientific principles.

This is coding in a nutshell. A 99223. This is what I think about when I’m admitting you through the emergency room. This is E&M medicine. This is Medicare medicine. This is how your government has decided the practice of medicine should be. To get paid, I must document what Medicare says I must in order to care for you, the patient. It doesn’t matter what I think is important to write in the chart. What matters is what is required to get paid and not be accused of fraud.

Like I have said before, the medical chart has become nothing more than a giant invoice for third parties to assert a sense of control on their balance sheet. It doesn’t matter who that third party is. They are all the same.. I’m telling you, it’s nothing more than a really inefficient game of cat and mouse. It is a terribly inefficient and expensive way to practice medicine.

And I might remind you, the exercise above was an example of just one patient on one day. I do this upwards of fifteen times a day. Every day. Day after day. Year after year. Oh yeah, and the rules are different for inpatient followup codes, discharge codes, critical care codes, and observation/admit same day codes. They all have their different requirements. And I have to get it right for every single patient I see. Every day. Over 2500 times a year. With the expectation of 100% accuracy.

Why? You see, in the eyes of Medicare, you are a nothing more than a 99223.

*This blog post was originally published at A Happy Hospitalist*

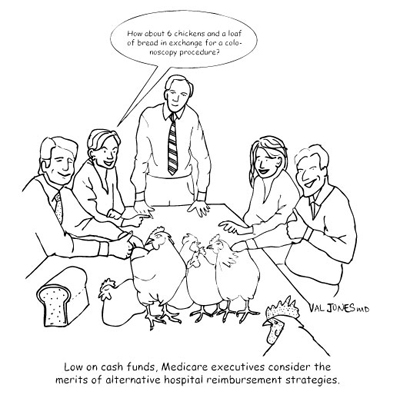

July 8th, 2009 by Dr. Val Jones in Health Policy, True Stories

4 Comments »

My mother-in-law just had a CT scan of her head in the Emergency Department of her local hospital. My husband called me to ask if I could “talk to her about her headache.”

Severe headaches in the elderly are indeed worrisome, and I wondered if she had fallen recently – if she might have a bleed in her brain requiring immediate surgery. Of course, she’d need a CT scan to rule that out… I was prepared for the worst. But what I learned by simply talking to Mrs. Zlotkus was unexpectedly revealing – not only about her diagnosis but about our healthcare system in general.

As it turns out, Mrs. Zlotkus had been having severe headaches for about 3 months. She was taking Vicodin daily to “take the edge off.” When I asked her about the location of the pain, she said that it was “just on one side of my head, from the top of my neck to the top of my head.” I asked her if the pain sometimes traveled to the other side, or if it involved her eye. “Never,” was her quick response. She also told me that she’d been seeing a physical therapist for 2.5 months for neck stretching exercises.

Mrs. Zlotkus told me her CT scan was negative, and that her blood tests didn’t show any “temporary arthritis.” (That’s temporal arteritis, I presume.)

“Well,” I said, “There’s only one thing left that I can think of that will give you a headache in the exact area you’re describing – and that’s shingles. Did you notice any scabs or painful bumps on your scalp when the headaches first started?”

“Why, yes!” Said Mrs. Zlotkus. “About 3 months ago I noticed some very painful, crusty scabs on my scalp. I thought for sure it was because my hairdresser used extra strong chemicals on my hair. I scolded her for it. She told me to put tea tree oil on it.”

Oh, boy. There it was – a diagnosis as plain as the nose on her face.

“Um… Well did you tell the ER docs about the scabs?”

“No. They never asked me about it and I didn’t see what my hairdresser’s chemical burn had to do with my severe headaches.”

My mother-in-law’s work up (ER visit, CT scan, several doctor visits, pain medicines), misdiagnosis (neck muscle stiffness), and mistreatment (physical therapy) for shingles probably cost upwards of $10,000. Worse than that, she did not get anti-viral treatment early enough in her outbreak to prevent a long-lasting pain syndrome (called post-herpetic neuralgia). Now that she has this shingles-related headache, it’s very hard to treat. And taking lots of acetaminophen-rich medications (Vicodin) is the last thing her liver needs right now.

So how did the healthcare system fail Mrs. Zlotkus? In my opinion, this is a great example of the “failure of synthesis” that Evan Falchuk discusses on his See First blog. Somehow, the physicians involved in Mrs. Zlotkus’ care didn’t take the time to think about her symptoms, to ask the right questions, and to put all the puzzle pieces together. Instead, they just ruled out the potential emergency issues (a stroke/hemorrhage, or temporal arteritis) and gave her a follow up appointment with a neurologist (who couldn’t fit her in their schedule for 2 months). They didn’t take a full history – they just dumped her in the most likely diagnostic category (neck stiffness) and let some other specialist follow up. Shameful.

I’ve described more egregious examples of hasty medical care on this blog – consider the case of an elderly woman (the mother of a friend of mine) who was misdiagnosed with “end stage dementia” when she really had acute delirium from an overdose of diuretics… Or the case of my girlfriend who was mistaken in the ER for a drug seeker when she was suffering from a kidney stone.

Sometimes I feel as if I have to keep an eye on all my friends and family before they set foot in a hospital, ER, or doctor’s office. I’m afraid that those providing their care will be so rushed and thoughtless that my loved ones will wind up with a huge bill, the wrong diagnosis, and perhaps even a near-death experience. I am seriously afraid for them.

The bottom line is that we have to stop rewarding providers for volume over quality. We have to value the history and physical exam beyond the CT scan and lab tests. We have to give doctors the chance to think about their patients – rather than turn up the speed dial on the clinical treadmills as a means to reduce costs.

My mother-in-law just spent $10,000 of our tax dollars on a diagnosis that could be made in 5 minutes of thoughtful questioning over the telephone. Multiply that cost by the number of other Medicare beneficiaries who are suffering similar misdiagnoses in this country and we’re talking serious money.

Under-thinking leads to over-testing. Has the CBO taken that into consideration in its scoring of various reform plans? I don’t think so. To me, this is yet another reason why we need physicians at the table in healthcare reform – we see the real cost drivers that others might not think of – even if some of us are too busy to diagnose shingles correctly!