December 1st, 2014 by Dr. Val Jones in Health Tips, Opinion

1 Comment »

Whenever possible I make a point of rounding on patients with their nurses present. I rely on nurses to be my eyes and ears when I’m not at the bedside. I need their input to confirm patient self-reports of everything from bowel and bladder habits to pain control, not to mention catching early warning signs of infection, mental status changes, or lapses in safety awareness. Oftentimes patients struggle to recall bathroom details, and they can inadvertently downplay pain control needs if they don’t happen to be in pain when I visit them. A quick check with their nurse can clarify (for example) that they are asking for pain medicine every 2 hours, that they have missed therapy due to somnolence, that their wound incision looks more red, and/or that they haven’t had a bowel movement in a dangerously long time. All critical details that I wouldn’t necessarily know from talking to the patient alone. Some of this information is not accurately captured in the electronic medical record either.

Whenever possible I make a point of rounding on patients with their nurses present. I rely on nurses to be my eyes and ears when I’m not at the bedside. I need their input to confirm patient self-reports of everything from bowel and bladder habits to pain control, not to mention catching early warning signs of infection, mental status changes, or lapses in safety awareness. Oftentimes patients struggle to recall bathroom details, and they can inadvertently downplay pain control needs if they don’t happen to be in pain when I visit them. A quick check with their nurse can clarify (for example) that they are asking for pain medicine every 2 hours, that they have missed therapy due to somnolence, that their wound incision looks more red, and/or that they haven’t had a bowel movement in a dangerously long time. All critical details that I wouldn’t necessarily know from talking to the patient alone. Some of this information is not accurately captured in the electronic medical record either.

On a recent trip to a new facility, I asked the head nurse when change of shift occurred. She was visibly perplexed and asked why I wanted to know. I explained that I planned to attend nursing sign out so that I’d be up to date on how my patients were doing. She raised her eyebrows to their vertical limit and responded, “I haven’t seen a doctor do nursing rounds in 30 years.”

That was one of the saddest things I’d heard in a long time. How is it that one of the fundamental features of medical care (doctors and nurses visiting patients together) has gone the way of the dinosaur? Most of my colleagues say they don’t round with nurses because they “don’t have time for that stuff” or that they can “flag down a nurse when there’s an issue” without needing scheduled communication. While I can sympathize with the fear of yet another “time suck” during a busy hospital day, I believe that rounding with nurses can actually save time, reduce medical errors, and head off developing problems at earlier stages (e.g. wound infections, intestinal obstructions, delirium, over/under medication and unwanted medication side effects).

You may think that coordinating nursing rounds with medical rounds is an insurmountable logistical nightmare, and if you have patients scattered throughout various floors of a hospital, that will certainly make things more difficult. But I have found ways to overcome these barriers, and highly recommend them to my peers:

1. Attend nursing sign out at change of shift if possible. Do not disrupt their hand-off process, but ask for clarification (or offer clarification) at key points during patient presentation.

2. Listen to the change of shift recording. Some nurses have their night shift team record their observations and findings in lieu of a 1:1 hand-off process during busy morning hours. This has its advantages and disadvantages. The good thing is that relaying information becomes asynchronous (i.e., like email vs a phone call – you don’t have to be present to get the info), the bad thing is that you can’t ask for clarification from the person delivering the information. If the nurses know in advance that the patient’s doctor is also listening in, they will leave targeted medical questions and concerns for you on the recording.

3. Do your rounds at times when medications are most commonly delivered. You will be more likely to run into a nurse in the patient’s room and can coordinate conversations as well as perform skin checks together.

4. Communicate with nurses (between rounds) when you are about to order a series of tests or dramatically change medication regimens. Explain why you’re doing it so they will be able to plan to execute your orders more efficiently (i.e. before the patient leaves for a radiologic study, etc.) This open communication will be appreciated and will be reciprocated (and may help to spark interest in joining you for regular rounds).

5. Invite nurses to round with YOU. If you can’t join their change of shift, consider having them join your medical rounds. You’ll need to negotiate this carefully as the goal is to streamline rounding processes, not double them.

A recent study published in the New England Journal of Medicine described a sign out process that reduced medical errors by 30%. This communication strategy involved 1:1 transfer of information about patients in a structured team environment (including nurses in some physician meetings). I anticipate that further investigation will reveal that interdisciplinary rounding (with nurses and doctors together) is a critical piece of the error reduction process. For all our advances in technology and digital information tracking, “old school” doctor-nurse rounds may prove to be more important in reducing errors and keeping our patients safe than other far more costly (and exasperating) interventions.

May 29th, 2014 by Dr. Val Jones in Health Policy, Opinion

4 Comments »

In an effort to save on human resources costs, some hospitals have decided to make locum tenens* doctors and nurses line items in a supply list. Next to IV tubing, liquid nutritional supplements and anti-bacterial wipes you’ll find slots for nurses, surgeons, and hospitalist positions. This depressing commoditization of professional staffing is a new trend in healthcare promoted by software companies promising to solve staffing shortages with vendor management systems (VMS). In reality, they are removing the careful provider recruiting process from job matching, causing a “race to the bottom” in care quality. Instead of filling a staff position with the most qualified candidates with a proven track record of excellent bedside manner and evidence-based practice, physicians and nurses with the lowest salary requirements are simply booked for work.

In an effort to save on human resources costs, some hospitals have decided to make locum tenens* doctors and nurses line items in a supply list. Next to IV tubing, liquid nutritional supplements and anti-bacterial wipes you’ll find slots for nurses, surgeons, and hospitalist positions. This depressing commoditization of professional staffing is a new trend in healthcare promoted by software companies promising to solve staffing shortages with vendor management systems (VMS). In reality, they are removing the careful provider recruiting process from job matching, causing a “race to the bottom” in care quality. Instead of filling a staff position with the most qualified candidates with a proven track record of excellent bedside manner and evidence-based practice, physicians and nurses with the lowest salary requirements are simply booked for work.

In a policy environment where quality measures and patient satisfaction ratings are becoming the basis for reimbursement rates, one wonders how VMS software is getting traction. Perhaps desperate times call for desperate measures, and the challenge of filling employment gaps is driving interest in impersonal digital match services? Rural hospitals are desperate to recruit quality candidates, and with a severe physician shortage looming, warm bodies are becoming an acceptable solution to staffing needs.

As distasteful as the thought of computer-matching physicians to hospitals may be, the real problems of VMS systems only become apparent with experience. After discussing user experience with several hospital system employees and reading various blogs and online debates here’s what I discovered:

1. Garbage In, Garbage Out. The people who input physician data (including their certifications, medical malpractice histories, and licensing data) have no incentive to insure accuracy of information. Head hunter agencies are paid when the physicians/nurses they enter into the database are matched to a hospital. To make sure that their providers get first dibs, they may leave out information, misrepresent availability, and in extreme cases, even falsify certification statuses. These errors are often caught during the hospital credentialing process, which results in many hours of wasted time on the part of internal credentialing personnel, and delays in filling the position. In other cases, the errors are not caught during credentialing and legal problems ensue when impaired providers are hired accidentally.

2. Limitation of choice. The non-compete contracts associated with VMS systems typically prevent hospital physician recruiters from contacting staffing agencies directly to fill their needs. This forces the hospital to rely on the database for all staffing leads. At least 68% of staffing agencies do not participate with VMS systems, so a large portion of the most carefully vetted professionals remain outside the VMS, inaccessible to those who contracted to use it.

3. Extra hospital employee training required. There are hundreds of proprietary VMS systems in use. Each one requires specialized training to manage everything from durable medical equipment to short term surgical staff. In cases where hospital staff are spread too thin to master this training, some VMS companies are pleased to provide a “managed service provider” or MSP to outsource the entire recruitment process. This adds additional layers, further removing the hospital recruiter from the physician.

4. Providers hate VMS systems. As anyone who has read a recent nursing blog can attest, VMS systems are universally despised by the potential employees they represent. VMS paints professionals in black and white, without the ability to distinguish quality, personality, or perform careful reference checks. They force down salaries, may rule out candidates based on where they live (travel costs), and provide no opportunity to negotiate salary vis-a-vis work load. When a hospital opts to use a VMS system as a middle man between them and the staffing agencies, the agencies often pass along the cost to the providers by offering them a lower hourly rate.

5. Provider privacy may be compromised. Once a physician or nurse curriculum vitae (CV) is entered into the VMS database the agency recruiter who entered it has 1 year (I can’t confirm that this is true for all systems) to represent them exclusively. After that, the CV is often available for any recruiter who has access to that VMS to view or pitch to any client. There is a wide variety of agency quality in the healthcare staffing industry, with some being highly ethical and selective in choosing their clients (only quality hospitals) and providers (carefully screened). Others are transactional, bottom-feeders with all the scruples of a used car salesman. When your data is in a VMS, one minute you might be represented by a caring, thoughtful recruiter who understands and respects your career needs, and the next (without your informed consent) you’ll be matched to a bankrupt hospital undergoing investigation by the Department of Health by a gum-chewing salesman who threatens you with a lawsuit if you don’t complete an assignment for half the pay you usually receive.

6. No cost savings, only increased liability. In the end, some hospitals who have tried VMS systems say that their decreased hiring costs have not resulted in overall savings. While they may see a downward shift in salary paid to their temporary work force, they get what they pay for. Just one “bad hire” who causes a medical malpractice lawsuit can eat up salary savings for an entire year of VMS. Not to mention the increased costs associated with a slower hiring process, attrition from poor fits, and the inconvenience of having to re-recruit for positions over and over again. Providers also lose out on career opportunities while they’re “on hold” during a prolonged hiring process. And for those who layer on a MSP, they lose control of the most important hospital quality and safety line of defense – choosing your own doctors and nurses.

In summary, while the idea of using a software matching service for recruiting physicians and nurses to hospitals sounds appealing at first, the bottom line is that reducing care providers to a group of numerical fields removes all the critical nuance from the hiring process. VMS, with their burdensome non-competes, cumbersome technology, and lack of quality control are an unwelcome new middle man in the healthcare staffing environment. It is my hope that they will be squeezed out of the business based on their own inability to provide value to a healthcare system that craves and rewards quality and excellence in its staff.

Job matching requires thoughtful hospital recruiters in partnership with ethical, experienced agencies. Choosing one’s hospital gauze vendor should involve a different selection algorithm than hiring a new chief of surgery. It’s time for physician and nurse groups to take a stand against this VMS-inspired commoditization of medicine before its roots sink in too deeply and we all become mere line items on a hospital vendor list. So next time you doctors and nurses plan to work a temporary assignment, ask your recruiter if they use a VMS system. Avoiding those agencies who do may mean a much better (and higher paying) work experience.

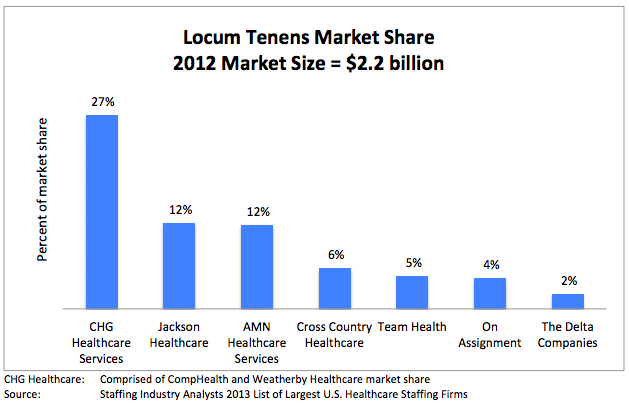

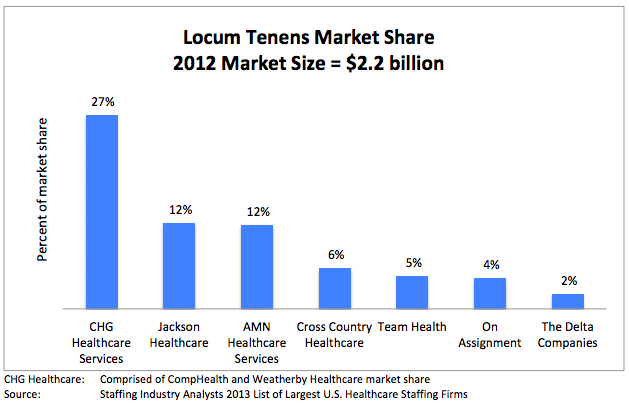

*Locum tenens (filling hospital staffing needs with part time or traveling physicians and nurses) is big business. Here is a run down of the estimated market size and its key industry leaders (provided by CompHealth):

August 15th, 2013 by Dr. Val Jones in Health Policy, Opinion

No Comments »

As I travel around the country, working in the trenches of various hospitals, I’ve been struck by the number of errors made by physicians and nurses whose administrative burden distracts them from patient care. The clinicians who make the errors are intelligent and competent – and they feel badly when an error is made. However, the volume of tasks required of them in a day (many of which are designed to fulfill an administrative “patient safety” or “quality enhancement” process) makes it impossible for them to complete any task in a comprehensive and thoughtful manner. In the end, administrators’ responses to increased error frequency is to increase error tracking and demand further documentation that leads to less time with patients and more errors overall. It’s a vicious cycle that people aren’t talking about enough.

As I travel around the country, working in the trenches of various hospitals, I’ve been struck by the number of errors made by physicians and nurses whose administrative burden distracts them from patient care. The clinicians who make the errors are intelligent and competent – and they feel badly when an error is made. However, the volume of tasks required of them in a day (many of which are designed to fulfill an administrative “patient safety” or “quality enhancement” process) makes it impossible for them to complete any task in a comprehensive and thoughtful manner. In the end, administrators’ responses to increased error frequency is to increase error tracking and demand further documentation that leads to less time with patients and more errors overall. It’s a vicious cycle that people aren’t talking about enough.

As I receive patient admissions from various referral hospitals, I rarely find a comprehensive discharge summary or full history and physical exam document that provides an accurate and complete account of the patient’s health status. Most of the documentation is poorly synthesized, scattered throughout reams of EMR-generated duplicative and irrelevant minutiae. Interpreting and sifting through this electronic data adds hours to my work day. Most physicians don’t bother to sift – which is why important information is missed in the mad dash to treat more patients per day than can be done safely and thoroughly.

I have personally witnessed many critical misdiagnoses caused by sloppy and rushed medical evaluations. I have had to transfer patients back to their originating surgical hospitals (at some of America’s top academic centers) for further work up and treatment, and have uncovered everything from cancer to brain disorders to medication errors for patients who had been evaluated and treated by many other specialists before me. No one seems to have the time to take a long hard look at these patients, and so they end up undergoing knee-jerk treatments for partially thought through diagnoses. The quality of medical care in which I’ve been engaged (over the past 20 years) has taken a dramatic turn for the worse because of volume overload (fueled by diminishing reimbursement) in the setting of excessive administrative and documentation requirements.

To use an analogy – The solution to the healthcare cost crisis is not to increase the speed of the assembly line belt when our physicians and nurses are already dropping items on the floor. First, stop asking them to step away from the belt to do other things. Second, put a cap on belt speed. Third, insure that you have sufficient staff to handle the volume of “product” on the belt, and support them with post-belt packaging and procedures that will prevent back up.

What we require most in healthcare is time to process our thoughts and engage in information synthesis. We must give physicians the time they need to complete a full, comprehensive, evaluation of each patient at regular intervals. We need nurses to be freed from desk clerk and safety documentation activities to actually inspect and manage their patients and alert physicians to new information.

Until hospitals and administrators recognize that more data does not result in better care, and that intelligent information synthesis (which requires clinician time, not computer algorithms) is the foundation of error prevention, I do not foresee a bright future for patients in this manic assembly line of a healthcare system.

December 27th, 2011 by BarbaraFicarraRN in Health Policy, Opinion

1 Comment »

Bill Crounse, MD, Senior Director, Worldwide Health, Worldwide Public Sector Microsoft Corporation shares his insights and describes four leading trends and technologies that will transform health and health care in 2012 and beyond.

These leading technologies include: cloud computing, health gaming, telehealth services and remote monitoring/mobile health.

Telehealth, Remote Monitoring, Mobile Health

I’d like to focus on telehealth and remote monitoring/mobile health since I feel telehealth is the nucleus of patient care, and telehealth can help reduce health care costs, and improve quality health care for patients. Telehealth technology combined mobile technology such as smartphones will make monitoring patients conditions easier and more efficient, and “cheaper and more scalable.”

Patient Quality Health Care

Through the Accountable Care Organizational Model (ACO), the core concept is to Read more »

*This blog post was originally published at Health in 30*

December 20th, 2011 by Linda Burke-Galloway, M.D. in News, Opinion

2 Comments »

Sometimes Fate has to shout in order to be heard, especially when the voice of reason is ignored. Michelle Duggar was pregnant with her 20th child to the aghast of many including this author. We squirmed in our seats. We moaned. We groaned. We blogged. The combination of Duggar’s 19 children and her advanced maternal age of 45 is enough to make any obstetrician or midwife cry, especially when she becomes pregnant, yet again. Not surprisingly, Duggar experienced a miscarriage with pregnancy number 20. According to media reports, when the Duggars presented for their ultrasound, a fetal heart beat could not be obtained. What occurred in obstetrical vernacular was a missed abortion or an early fetal demise. Based on the Duggars’ press release, his wife probably had no symptoms prior to receiving the ultrasound. The cramping, spotting, abdominal and back pain was probably absent. An early fetal demise without symptoms or missed abortion means the baby stopped growing because there was a condition present that was incompatible with life. Did Duggar’s age increase her chances of having a miscarriage? Read more »

Sometimes Fate has to shout in order to be heard, especially when the voice of reason is ignored. Michelle Duggar was pregnant with her 20th child to the aghast of many including this author. We squirmed in our seats. We moaned. We groaned. We blogged. The combination of Duggar’s 19 children and her advanced maternal age of 45 is enough to make any obstetrician or midwife cry, especially when she becomes pregnant, yet again. Not surprisingly, Duggar experienced a miscarriage with pregnancy number 20. According to media reports, when the Duggars presented for their ultrasound, a fetal heart beat could not be obtained. What occurred in obstetrical vernacular was a missed abortion or an early fetal demise. Based on the Duggars’ press release, his wife probably had no symptoms prior to receiving the ultrasound. The cramping, spotting, abdominal and back pain was probably absent. An early fetal demise without symptoms or missed abortion means the baby stopped growing because there was a condition present that was incompatible with life. Did Duggar’s age increase her chances of having a miscarriage? Read more »

*This blog post was originally published at Dr. Linda Burke-Galloway*

Whenever possible I make a point of rounding on patients with their nurses present. I rely on nurses to be my eyes and ears when I’m not at the bedside. I need their input to confirm patient self-reports of everything from bowel and bladder habits to pain control, not to mention catching early warning signs of infection, mental status changes, or lapses in safety awareness. Oftentimes patients struggle to recall bathroom details, and they can inadvertently downplay pain control needs if they don’t happen to be in pain when I visit them. A quick check with their nurse can clarify (for example) that they are asking for pain medicine every 2 hours, that they have missed therapy due to somnolence, that their wound incision looks more red, and/or that they haven’t had a bowel movement in a dangerously long time. All critical details that I wouldn’t necessarily know from talking to the patient alone. Some of this information is not accurately captured in the electronic medical record either.

Whenever possible I make a point of rounding on patients with their nurses present. I rely on nurses to be my eyes and ears when I’m not at the bedside. I need their input to confirm patient self-reports of everything from bowel and bladder habits to pain control, not to mention catching early warning signs of infection, mental status changes, or lapses in safety awareness. Oftentimes patients struggle to recall bathroom details, and they can inadvertently downplay pain control needs if they don’t happen to be in pain when I visit them. A quick check with their nurse can clarify (for example) that they are asking for pain medicine every 2 hours, that they have missed therapy due to somnolence, that their wound incision looks more red, and/or that they haven’t had a bowel movement in a dangerously long time. All critical details that I wouldn’t necessarily know from talking to the patient alone. Some of this information is not accurately captured in the electronic medical record either.

In an effort to save on human resources costs, some hospitals have decided to make locum tenens* doctors and nurses line items in a supply list. Next to IV tubing, liquid nutritional supplements and anti-bacterial wipes you’ll find slots for nurses, surgeons, and hospitalist positions. This depressing commoditization of professional staffing is a new trend in healthcare promoted by software companies promising to solve staffing shortages with vendor management systems (VMS). In reality, they are removing the careful provider recruiting process from job matching, causing a “race to the bottom” in care quality. Instead of filling a staff position with the most qualified candidates with a proven track record of excellent bedside manner and evidence-based practice, physicians and nurses with the lowest salary requirements are simply booked for work.

In an effort to save on human resources costs, some hospitals have decided to make locum tenens* doctors and nurses line items in a supply list. Next to IV tubing, liquid nutritional supplements and anti-bacterial wipes you’ll find slots for nurses, surgeons, and hospitalist positions. This depressing commoditization of professional staffing is a new trend in healthcare promoted by software companies promising to solve staffing shortages with vendor management systems (VMS). In reality, they are removing the careful provider recruiting process from job matching, causing a “race to the bottom” in care quality. Instead of filling a staff position with the most qualified candidates with a proven track record of excellent bedside manner and evidence-based practice, physicians and nurses with the lowest salary requirements are simply booked for work.

As I

As I