February 2nd, 2015 by Dr. Val Jones in Health Policy, Opinion

1 Comment »

Electronic medical record systems (EMRs) have become a part of the work flow for more than half of all physicians in the U.S. and incentives are in place to bring that number up to 100% as soon as possible. Some hail this as a giant leap forward for healthcare, and in theory that is true. Unfortunately, EMRs have not yet achieved their potential in practice – as I have discussed in my recent blog posts about “how an EMR gave my patient syphillis,” in the provocative “EMRs are ground zero for the deterioration of patient care,” and in my explanation of how hospital pharmacists are often the last layer of protection against medical errors of EPIC proportions.

Electronic medical record systems (EMRs) have become a part of the work flow for more than half of all physicians in the U.S. and incentives are in place to bring that number up to 100% as soon as possible. Some hail this as a giant leap forward for healthcare, and in theory that is true. Unfortunately, EMRs have not yet achieved their potential in practice – as I have discussed in my recent blog posts about “how an EMR gave my patient syphillis,” in the provocative “EMRs are ground zero for the deterioration of patient care,” and in my explanation of how hospital pharmacists are often the last layer of protection against medical errors of EPIC proportions.

Considering that an EMR costs the average physician up to $70,000 to implement, and hospital systems in the hundreds of millions – it’s not surprising that the main “benefit” driving their adoption is improved coding and billing for reimbursement capture. The efficiencies associated with access to digital patient medical records for all Americans is tantalizing to government agencies and for-profit insurance companies managing the bill for most healthcare. But will this collective data improve patient care and save lives, or is it mostly a financial gambit for medical middle men? At this point, it seems to be the latter.

There are, however, some true benefits of EMRs that I have experienced – and to be fair, I wanted to provide a personal list of pros and cons for us to consider. Overall however, it seems to me that EMRs are contributing to a depersonalization of medicine – and I grieve for the lost hours genuine human interaction with my patients and peers. Though the costs of EMR implementation may be recouped with aggressive billing tactics, what we’re losing is harder to define. As the old saying goes, “What good is it for someone to gain the whole world, yet forfeit their soul?”

| Pros Of EMR |

Cons Of EMR |

| Solves illegible handwriting issue |

Obscures key information with redundancy |

| Speeds process of order entry and fulfillment |

Difficult to recall errors in time to stop/change |

| May reduce redundant testing as old results available |

Facilitates excessive testing due to ease of order entry |

| Allows cut and paste for rapid note writing |

Encourages plagiarism in lieu of critical thinking |

| Improves ease of coding and billing to increase reimbursement |

Allows easy upcoding and overcharging |

| Reminds physicians of evidence-based guidelines at point of care |

Takes focus from patient to computer |

| Improves data mining capabilities for research and quality improvement |

Facilitates data breaches and health information hacking |

| Has potential to improve information portability and inter-operability |

Has potential to leak personal healthcare information to employers and insurers |

| May reduce errors associated with human element |

May increase carry forward errors and computer-generated mistakes |

| Automated reminders keep documentation complete |

May increase “alert fatigue,” causing providers to ignore errors/drug interactions |

| Can be accessed from home |

Steep learning curve for optimal use |

| Can view radiologic studies and receive test results in one place |

Very expensive investment: staff training, tech support, ongoing software updates, etc. |

| More tests available at the click of a button |

Encourages reliance on tests rather than physical exam/history |

| Makes medicine data-centric |

Takes time away from face-to-face encounters |

| Improved coordination of care |

Decrease in verbal hand-offs, causing key information to be lost |

| Accessibility of health data to patients |

Potential for increased legal liability for physicians |

January 13th, 2015 by Dr. Val Jones in Health Policy, Opinion

7 Comments »

It’s no secret that medicine has become a highly specialized business. While generalists used to be in charge of most patient care 50 years ago, we have now splintered into extraordinarily granular specialties. Each organ system has its own specialty (e.g. gastroenterology, cardiology), and now parts of systems have their own experts (hepatologists, cardiac electrophysiologists) Even ophthalmologists have subspecialized into groups based on the part of the eye that they treat (retina specialists, neuro-ophthalmologists)!

It’s no secret that medicine has become a highly specialized business. While generalists used to be in charge of most patient care 50 years ago, we have now splintered into extraordinarily granular specialties. Each organ system has its own specialty (e.g. gastroenterology, cardiology), and now parts of systems have their own experts (hepatologists, cardiac electrophysiologists) Even ophthalmologists have subspecialized into groups based on the part of the eye that they treat (retina specialists, neuro-ophthalmologists)!

This all comes as a response to the exponential increase in information and technology, making it impossible to truly master the diagnosis and treatment of all diseases and conditions. A narrowed scope allows for deeper expertise. But unfortunately, some of us forget to pull back from the minutiae to respect and appreciate what our peers are doing.

This became crystal clear to me when I read an interview with a cardiologist on the NPR blog. Dr. Eric Topol was making some enthusiastically sweeping statements about how technology would allow most medical care to take place in patient’s homes. He says,

“The hospital is an edifice we don’t need except for intensive care units and the operating room. [Everything else] can be done more safely, more conveniently, more economically in the patient’s bedroom.”

So with a casual wave of the hand, this physician thought leader has described a world without my specialty (Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation) – and all the good that we do to help patients who are devastated by sudden illness and trauma. I can’t imagine a patient with a high level spinal cord injury being sent from the ER to his bedroom to enjoy all the wonderful smartphone apps “…you can get for $35 now from China.” No, he needs ventilator care and weaning, careful monitoring for life-threatening autonomic dysreflexia, skin breakdown, bowel and bladder management, psychological treatment, and training in the use of all manner of assistive devices, including electronic wheelchairs adapted for movement with a sip and puff drive.

I’m sure that Dr. Topol would blush if he were questioned more closely about his statement regarding the lack of need for hospital-based care outside of the OR, ER and ICU. Surely he didn’t mean to say that inpatient rehab could be accomplished in a patient’s bedroom. That people could simply learn how to walk and talk again after a devastating stroke with the aid of a $35 smartphone?

But the problem is that policy wonks listen to statements like his and adopt the same attitude. It informs their approach to budget cuts and makes it ten times harder for rehab physicians to protect their facilities from financial ruin when the prevailing perception is that they’re a waste of resources because they’re not an ICU. Time and again research has shown that aggressive inpatient rehab programs can reduce hospital readmission rates, decrease the burden of care, improve functional independence and long term quality of life. But that evidence isn’t heeded because perception is nine tenths of reality, and CMS continues to add onerous admissions restrictions and layers of justification documentation for the purpose of decreasing its spend on inpatient rehab, regardless of patient benefit or long term cost savings.

Physician specialists operate in silos. Many are as far removed from the day-to-day work of their peers as are the policy wonks who decide the fate of specialty practices. Physicians who have an influential voice in healthcare must take that honor seriously, and stop causing friendly fire casualties. Because in this day and age of social media where hard news has given way to a cult of personality, an offhanded statement can color the opinion of those who hold the legislative pen. I certainly hope that cuts in hospital budgets will not land me in my bedroom one day, struggling to move and breathe without the hands-on care of hospitalists, nurses, therapists, and physiatrists – but with a very nice, insurance-provided Chinese smartphone.

October 17th, 2014 by Dr. Val Jones in Opinion, True Stories

No Comments »

Electronic medical records (EMRs) now play a part in the daily documentation routine for most physicians. While improvements in access to patient data, legibility of notes, and ease of order entry are welcome enhancements, there is a significant downside to EMRs as well. Although I’ve blogged about my frustrations with nonsensical, auto-populated notes and error carry-forward, there is a more insidious problem with reliance on EMRs: digital dependency.

Electronic medical records (EMRs) now play a part in the daily documentation routine for most physicians. While improvements in access to patient data, legibility of notes, and ease of order entry are welcome enhancements, there is a significant downside to EMRs as well. Although I’ve blogged about my frustrations with nonsensical, auto-populated notes and error carry-forward, there is a more insidious problem with reliance on EMRs: digital dependency.

The idea of digital dependency first occurred to me during a conversation with a young medical resident at a hospital where we share patients. I was bemoaning the fact that I was being forced to use hospital-designed templates for admission notes, rather than a dictation system or carefully crafted note of my own choosing. She looked at me, wide-eyed and said:

“You’ve worked without templates? How do you even know where to begin? Can you really dictate an entire note off the top of your head? I couldn’t live without templates.”

As I stared back at her with an equal amount of bewilderment, I slowly realized that her thinking had been honed for drop-down menus and check boxes. Over time, she had lost the ability to construct narratives, create a cohesive case for her diagnostic impressions, and justify her patient plan of action. To this bright, highly trained mind, clinical reasoning was an exercise in multiple choice selection. Her brain had been optimized for the demands of an EMR template, and mine was a relic of the pre-EMR era. I was witnessing a fundamental cognitive shift in the way that medicine was practiced.

The problem with “drop-down medicine” is that the advantages of the human mind are muted in favor of data entry. Physicians in this model essentially provide little benefit over a computer algorithm. Intuition, clinical experience, sensory input (the smell of pseudomonas, the sound of pulmonary edema, the pulsatile mass of an aneurysm) are largely untapped. We lose our need for team communication because “refer to my EMR note” is the way of the future. Verbal sign-outs are a thing of the past it seems, as those caring for the same patient rely on their digital documentation to serve in place of human interaction.

My advice to the next generation of physicians is to limit your dependency on digital data. Like alcohol, a little is harmless or possibly healthy, but a lot can ruin you. Leverage the convenience of the EMR but do not let it take over your brain or your patient relationships. Pay attention to what your senses tell you during your physical exam, take a careful history, listen to family members, discuss diagnostic conundrums with your peers, and always take the time for verbal sign outs. Otherwise, what advantage do you provide to patients over a computer algorithm?

Am I a curmudgeon who is bristling against forward progress, or do I have a reasonable point? Judging from the fact that my young peers copy and paste my assessment and plans into their progress notes with impressive regularity, I’d say that templatized medicine still can’t hold a candle to thoughtful prose. Even the digitally dependent know this. 🙂

April 28th, 2014 by Dr. Val Jones in Health Tips, Opinion

1 Comment »

As I travel the country providing coverage for inpatient rehab units, I have been struck by the generally high quality of nursing care. Excellent nurses are the glue that holds a hospital unit together. They sound the first alarm when a patient’s health is at risk, they double-check orders and keep an eye out for medical errors. Nurses spend more time with patients than any other hospital staff, and they are therefore in the best position to comment on patient progress and any changes in their condition. An observant nurse nips problems in the bud – and this saves lives.

As I travel the country providing coverage for inpatient rehab units, I have been struck by the generally high quality of nursing care. Excellent nurses are the glue that holds a hospital unit together. They sound the first alarm when a patient’s health is at risk, they double-check orders and keep an eye out for medical errors. Nurses spend more time with patients than any other hospital staff, and they are therefore in the best position to comment on patient progress and any changes in their condition. An observant nurse nips problems in the bud – and this saves lives.

Not only are nurses under-appreciated and under-paid, they are suffering as much as physicians are with new digital documentation requirements. Just as patients are receiving less face time with their physicians, they are also suffering from a reduction in bedside attention from nurses. The need to record data has supplanted our ability to listen to the patient, causing anguish for patients, physicians, and nurses alike.

This being our lot (and with continued “quality improvement” policies that will simply add to the documentation burden) we must find ways to optimize patient care despite inane bureaucratic intrusions. I believe that there are some steps that nurses and doctors can take to improve patient care right now:

1. Minimize “floating.” (Floating is when a nurse is pulled from one part of the hospital to fill in for a gap in coverage in a different unit). It is extremely difficult for nurses to take care of a floor full of patients they’ve never met before. Every time that care of a patient is handed off to someone else (be they MD or RN), there is a risk of forgetting to follow through with a test, procedure, or work up. Simply knowing what “normal” looks like for a given patient can be incredibly important.

For example, left sided weakness is not concerning in a patient with a long-time history of stroke, but what if that is a new finding? If you’ve never met the patient before, you might not realize that the weakness is new and constitutes an emergency. How does a nurse know if a patient’s skin ulcer/rash/pain etc. is better or worse than yesterday? Verbal reports don’t always clarify sufficiently. There are endless advantages to minimizing staff turnover during a patient’s hospital stay. Reducing the total number of nurses who care for individual patients should be a number one priority in hospitals.

2. If you see something, say something. There are a host of reasons why nurses may be hesitant to report patient symptoms. Either they don’t know the patient well and think that the new issue could be “normal” for that patient, or perhaps the physician managing the patient has been unreceptive to previous notifications. However, I am always grateful when a nurse goes out of her way to tell me her concerns, because I generally find that she’s on to something important. My general rule is to over-communicate. If you see something, say something – because that episode of patient anxiety in the middle of the night could be a heart attack. And if I don’t know it’s happening, I can’t fix it.

3. Please don’t diagnose patients without input. I’ve found that nurses generally have excellent instincts about patients, and many times they correctly pinpoint their diagnosis. But other times they can be misled, which can impair their care priorities. For example, I had a patient who was having some difficulty breathing. The nurse told me about it immediately (which was great) but then she proceeded to assume that it was caused by a pulmonary embolism. I explained why I didn’t think this was the case, but she was quite insistent. So much so that when another patient began to have unstable vital signs (and I requested her help with preparing for a rapid response) she stayed with the former patient, believing that his problem was more acute. This doesn’t happen that frequently, but I think it serves as a reminder that physicians and nurses work best as a team when diagnostic conundrums exist.

4. Help me help you. Please do not hesitate to come to me when we need to clean up the EMR orders. If the patient has had blood glucose finger stick checks of about 100 at each of 4 checks every day for 2 weeks, then by golly let’s reduce the checking frequency! If the EMR lists Q4 hour weight checks (because the drop down box landed on “hour” instead of “day” when it was being ordered) I’d be happy to fix it. If a digital order appears out of the ordinary, ask the doctor about it. Maybe it was a mistake? Or maybe there’s a reason for Q4 hour neuro checks that you need to be aware of?

5. Let’s round together. Nurses and physicians should really spend more time talking about patients together. I know that some physicians may be resistant to attending nursing rounds due to time constraints, but I’ve found that there’s no better way to keep a unit humming than to comb through the patient cases carefully one time each day.

This may sound burdensome, but it ends up saving time, heads off problems, and gives nurses a clearer idea of what to look out for. Leaving nurses in the dark about your plan for the patient that day is not helpful – they end up searching through progress notes (for example) to try to guess if the patient is going to radiology or not, and how to schedule their meds around that excursion. Alternately, when it comes time to update your progress note, isn’t it nice to have the latest details on the patient’s condition? Nurses and doctors can save each other a lot of time with a quick, daily debrief.

6. Show me the wounds. Many patients have skin breakdown, rashes, or sores. These are critically important to treat and require careful observation to prevent progression. Doctors want to see wounds at regular intervals, but don’t always take the time to unwrap or turn the patient in order to get a clear view. Alternatively, some MDs simply unwrap/undress wounds at will, leaving the patient’s room without even telling the nurse that they need to be re-wrapped. In some cases, it takes a lot of time to re-dress the complex wound, adding a lot of work to the nurse’s already busy schedule (and offering little benefit, and some degree of discomfort, to the patient).

Nurses, on the other hand, have the opportunity to see wounds more frequently as they provide dressing changes or peri-care at regular intervals. Most nurses and doctors don’t seem to have a good process in place for wound checks. I usually make a deal with nurses that I won’t randomly destroy their dressing changes if they promise to call me to the patient’s bedside when they are in the middle of a scheduled change. This works fairly well, so long as I’m willing/able to drop everything I’m doing for a quick peek.

These are my top suggestions from my most recent travels. I’d be interested in hearing what nurses think about these suggestions, and if they have others for physicians. I’m always eager to improve my patient care, and optimizing my nursing partnerships is a large part of that. 😆

April 21st, 2014 by Dr. Val Jones in Opinion, True Stories

2 Comments »

For the past couple of years I’ve been working as a traveling physician in 13 states across the U.S. I chose to adopt the “locum tenens lifestyle” because I enjoy the challenge of working with diverse teams of peers and patient populations. I believe that this kind of work makes me a better doctor, as I am exposed to the widest possible array of technology, specialist experience, and diagnostic (and logistical) conundrums. During my down times I like to think about what I’ve learned so that I can try to make things better for my next group of patients.

For the past couple of years I’ve been working as a traveling physician in 13 states across the U.S. I chose to adopt the “locum tenens lifestyle” because I enjoy the challenge of working with diverse teams of peers and patient populations. I believe that this kind of work makes me a better doctor, as I am exposed to the widest possible array of technology, specialist experience, and diagnostic (and logistical) conundrums. During my down times I like to think about what I’ve learned so that I can try to make things better for my next group of patients.

This week I’ve been considering how in-patient doctoring has changed since I was in medical school. Unfortunately, my experience is that most of the changes have been for the worse. While we may have a larger variety of treatment options and better diagnostic capabilities, it seems that we have pursued them at the expense of the fundamentals of good patient care. What use is a radio-isotope-tagged red blood cell nuclear scan if we forget to stop giving aspirin to someone with a gastrointestinal bleed?

At the risk of infecting my readers with a feeling of helplessness and depressed mood, I’d like to discuss my findings in a series of blog posts. Today’s post is about why electronic medical charts have become ground zero for deteriorating patient care.

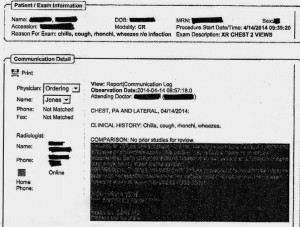

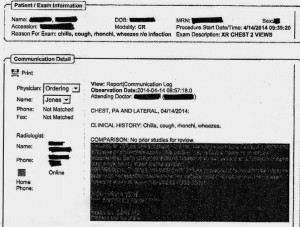

EMR Alert - Featuring radiologist note in illegible font color

1. Medical notes are no longer used for effective communication, but for billing purposes. When I look back at the months of training I received at my alma mater regarding the proper structure of intelligent medical notes, I recall with nostalgia how beautiful they were. Each note was designed to present all the observed and collected data in a cohesive and logical format, justifying the physician’s assessment and treatment plan. Our impressions of the patient’s physical and mental condition, reasons for further testing, and our current thought processes regarding optimal treatments and follow up (including citation of scientific literature to justify the chosen course) were all crisply presented.

Nowadays, medical notes consist of randomly pre-populated check box data lifted from multiple author sources and vomited into a nonsensical monstrosity of a run-on sentence. It’s almost impossible to figure out what the physician makes of the patient or what she is planning to do. Occasional “free text” boxes can provide clues, when the provider has bothered to clarify. One needs to be a medical detective to piece together an assessment and plan these days. It’s both embarrassing and tragic… if you believe that the purpose of medical notes is effective communication. If their purpose is justifying third-party payer requirements, then maybe they are working just fine?

My own notes have been co-opted by the EMRs, so that when I get the chance to free-text some sensible content, it still forces gobbledygook in between. I can see why many of my peers have eventually “given up” on charting properly. No one (except coders and payers interested in denying billing claims) reads the notes anymore. The vicious cycle of unintelligible presentation drives people away from reading notes, and then those who write notes don’t bother to make them intelligent anymore. There is a “learned helplessness” that takes over medical charting. All of this could (I suppose) be forgiven if physicians reverted back to verbal handoffs and updates to other staff/peers caring for patients to solve this grave communication gap. Unfortunately, creating gobbledygook takes so much time that there is less old fashioned verbal communication than ever.

2. No one talks to each other anymore. I’m not sure if this is because of a general cultural shift away from oral communication to text-based, digital intermediaries (think zombie-like teens texting one another incessantly) or if it’s related to sheer time constraints. However, I am continually astonished by the lack of face-to-face or verbal communication going on in hospitals these days. When I first observed this phenomenon, I attributed it to the facility where I was working. However, experience has shown that this is an endemic problem in the entire healthcare system.

When you are overworked, it’s natural to take the path of least resistance – checking boxes and ordering consults in the EMR is easier than picking up a phone and constructing a coherent patient presentation to provide context for the specialist who is about to weigh in on disease management. Nursing orders are easier to enter into a computer system than actually walking over and explaining to him/her what you intend for the patient and why.

But these shortcuts do not save time in the long run. When a consultant is unfamiliar with the partial workup you’ve already completed, he will start from the beginning, with duplicate testing and all its associated expenses, risks, and rabbit trails. When a nurse doesn’t know that you’ve just changed the patient to “NPO” status (or for what reason) she may give him/her scheduled medications before noticing the change. When you haven’t explained to the physical therapists why it could be dangerous to get a patient out of bed due to a suspected DVT, the patient could die of a sudden pulmonary embolism. Depending upon computer screen updates for rapid changes in patient care plans is risky business. EMRs are poor substitutes for face-to-face communication.

In one case I remember a radiology tech expressing amazement that I had bothered to type the reason for the x-ray in the order field. How can a radiologist be expected to rule out something effectively if he isn’t given the faintest hint about what he’s looking for? On another occasion I called to speak with the radiologist on a complicated case where the patient’s medical history provided him with a clue to look for something he hadn’t thought of – and his re-read of the CT scan led to the discovery and treatment of a life-threatening disease. Imagine that? An actual conversation saved a life.

3. It’s easy to be mindless with electronic orders. There’s something about the brain that can easily slip into “idle” mode when presented with pages of check boxes rather than a blank field requiring original input. I cannot count the number of times that I’ve received patients (from outside hospitals) with orders to continue medications that should have been stopped (or forgotten medications that were not on the list to be continued). In one case, for example, a patient with a very recent gastrointestinal bleed had aspirin listed in his current medication list. In another, the discharging physician forgot to list the antibiotic orders, and the patient had a partially-treated, life-threatening infection.

As I was copying the orders on these patients, I almost made the same mistakes. I was clicking through boxes in the pharmacy’s medication reconciliation records and accidentally approved continuation of aspirin (which I fortunately caught in time to cancel). It’s extremely unlikely that I would have hand-written an order for aspirin if I were handling the admission in the “old fashioned” paper-based manner. My brain had slipped into idle… my vigilance was compromised by the process.

In my view, the only communication problem that EMRs have solved is illegible handwriting. But trading poor handwriting for nonsensical digital vomit isn’t much of an advance. As far as streamlining orders and documentation is concerned, yes – ordering medications, tests, and procedures is much faster. But this speed doesn’t improve patient care any more than increasing the driving speed limit from 60 mph to 90 mph would reduce car accidents. Rapid ordering leads to more errors as physicians no longer need to think carefully about everything. EMRs have sped up processes that need to be slow, and slowed down processes that need to be fast. From a clinical utility perspective, they are doing more harm than good.

As far as coding and billing are concerned, I suppose they are revolutionary. If hospital care is about getting paid quickly and efficiently then perhaps we’re making great strides? But if we are expecting EMRs to facilitate care quality and communication, we’re in for a big disappointment. EMRs should have remained a back end billing tool, rather than the hub of all hospital activity. It’s like using Quicken as your life’s default browser. Over-reach of this particular technology is harming our patients, undermining communication, and eroding critical thinking skills. Call me Don Quixote – but I’m going to continue tilting at the hospital EMR* windmill (until they are right-sized) and engage in daily face-to-face meetings with my peers and hospital care team.

*Note: there is at least one excellent, private practice EMR (called MD-HQ). It is for use in the outpatient setting, and is designed for communication (not billing). It is being adopted by direct primary care practices and was created by physicians for supporting actual thinking and relevant information capture. I highly recommend it!

Electronic medical record systems (EMRs) have become a part of the work flow for more than half of all physicians in the U.S. and incentives are in place to bring that number up to 100% as soon as possible. Some hail this as a giant leap forward for healthcare, and in theory that is true. Unfortunately, EMRs have not yet achieved their potential in practice – as I have discussed in my recent blog posts about “how an EMR gave my patient syphillis,” in the provocative “EMRs are ground zero for the deterioration of patient care,” and in my explanation of how hospital pharmacists are often the last layer of protection against medical errors of EPIC proportions.

Electronic medical record systems (EMRs) have become a part of the work flow for more than half of all physicians in the U.S. and incentives are in place to bring that number up to 100% as soon as possible. Some hail this as a giant leap forward for healthcare, and in theory that is true. Unfortunately, EMRs have not yet achieved their potential in practice – as I have discussed in my recent blog posts about “how an EMR gave my patient syphillis,” in the provocative “EMRs are ground zero for the deterioration of patient care,” and in my explanation of how hospital pharmacists are often the last layer of protection against medical errors of EPIC proportions.

It’s no secret that medicine has become a highly specialized business. While generalists used to be in charge of most patient care 50 years ago, we have now splintered into extraordinarily granular specialties. Each organ system has its own specialty (e.g. gastroenterology, cardiology), and now parts of systems have their own experts (hepatologists, cardiac electrophysiologists) Even ophthalmologists have subspecialized into groups based on the part of the eye that they treat (retina specialists, neuro-ophthalmologists)!

It’s no secret that medicine has become a highly specialized business. While generalists used to be in charge of most patient care 50 years ago, we have now splintered into extraordinarily granular specialties. Each organ system has its own specialty (e.g. gastroenterology, cardiology), and now parts of systems have their own experts (hepatologists, cardiac electrophysiologists) Even ophthalmologists have subspecialized into groups based on the part of the eye that they treat (retina specialists, neuro-ophthalmologists)!

For the past couple of years I’ve been working as a traveling physician in 13 states across the U.S. I chose to adopt the “

For the past couple of years I’ve been working as a traveling physician in 13 states across the U.S. I chose to adopt the “