May 5th, 2010 by Toni Brayer, M.D. in Better Health Network, Health Policy, Opinion, Research

1 Comment »

The new healthcare reform law, which is called the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), will be a huge disappointment to the millions of previously-uninsured people who finally purchase insurance policies when they try to find a doctor.

Primary care physicians are already in short supply and the most popular ones have closed practices or long waits for new patients. Imagine when 2014 hits and all of those patients come calling. Who is going to be available to treat them? Read more »

*This blog post was originally published at EverythingHealth*

April 29th, 2009 by AlanDappenMD in Primary Care Wednesdays, Uncategorized

3 Comments »

In early 2006, four years into running my current medical practice, doctokr Family Medicine, I got a call from my medical malpractice carrier. Just weeks before I’d received a notice that my malpractice rates could go up by more than 25%. The added news of a pending investigatory audit was chilling. In 25 years of practicing medicine I’d never been audited.

“Is there a complaint, or a law suit against me that I don’t know about?”

“No,” the auditor told me over the phone, “We’ve never seen a medical practice like yours and feel obligated to investigate your process from a medical-legal perspective.”

“Great,” I thought, with a weary sigh. “I’m already battling the insurance model, the status quo of the medical business model, and slow adoption by consumers who are addicted to their $20 co-pay. All I’m trying to do is to breathe life into primary care and get the consumer a much higher quality service for less money than currently subsidized through the insurance model. And now this.”

The time had arrived to add the concerns of the malpractice companies to the list of hurdles to clear if a new vision of a medical care model was ever to catch flight.

I frequently am asked the question “Aren’t you afraid of the malpractice risk?” when I explain my medical practice model, which is based on the doctor answering the phone 24/7, resulting in the patient’s medical problem being solved by the phone more 50% of the time. The simplest counter to this question is to analyze the risk patients incur when the doctor won’t answer the phone. What happens when the doctor is the LAST person to know what’s going on with patients? The answer is obvious. But malpractice companies could have concerns beyond patient safety. Buy-in from the malpractice companies would be critical to the future viability of all telemedicine.

I prepared a summary paper, which included 12 bullet points, explaining how a doctor- patient relationship based on trust , transparency, continuous communications and high quality information systems significantly reduce risk to the person you’re trying to help.

Bullet 1: The industry standard is that 70% of malpractice cases in primary care center on communication barriers. My medical team deploys continuous phone and email communications and 7 days a week- same day office visits when needed between doctor and patient thus significantly reducing these barriers.

.

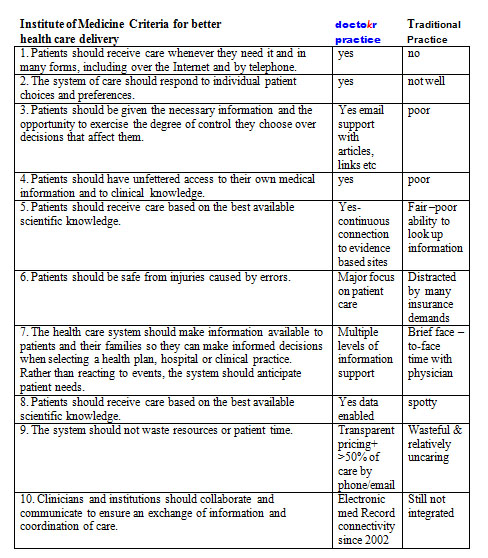

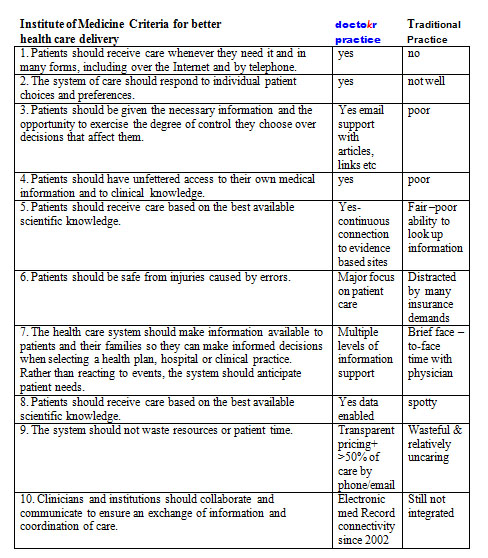

The remaining bullets could be summarized by the conclusions from the Institute of Medicine’s visionary book Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century using a table developed by The American Medical News when they reviewed the book. I carefully plotted our practice standards compared to the traditional business model as it stands today based on this table:

The auditor showed up, spent 4 hours reviewing our practice, electronic medical records, compliance to HIPPA, our intakes, on-line connectivity, procedures, and practice standards. While the auditor reviewed, I sat as unobtrusively as I could, feeling my brow grow damp with perspiration, as I carefully answered her questions. During the auditor’s time, I never moved to sway her to “my way.” I just let the data that I had accumulated from four years of practice do the talking.

Once the auditor left, I waited for two weeks for the results. By the time their letter arrived, I was scared to open it. The news arriving made me jubilant. The medical practice company announced a DECREASE in my premiums because we used telemedicine and EMR to treat patients so fast (often within 10 minutes of someone calling us we have their issue solved without the patient ever having to come in).

I will admit that I felt, and actually still do feel, vindicated by having my malpractice insurer understand fully the value that the type of telemedicine my practice offers to our patients: round-the-clock access to the doctor, speed of diagnosis, and convenience, which all led to healthier patients and lower risk.

Doctors answering the phone all day for their patients, it’s not just lower risk, it’s better health care at a better price. It’s a win-win-win strategy whose day is arriving.

Until next week, I remain yours in primary care,

Alan Dappen, MD

April 8th, 2009 by AlanDappenMD in Primary Care Wednesdays

No Comments »

Back in 1983, as a third year medical student, I read a study stating that 80% of medical visits were not needed. After finishing the text, I remember thinking, “Hmm, there aren’t that many hypochondriacs in our office!”

It wasn’t until I had practiced medicine for 20 years that I finally understood this statement for what it really meant: doctors were not helping patients through remote means, instead insisting on seeing patients in the office for all medical issues, even the most routine of issues out of habit, out of fear, out of how to get paid.

In 1996, I set out to prove that allowing established patients to remotely access doctors for care would improve their medical outcomes. I convinced my medical partners to let me conduct an experiment: I would work a few half days on the phones, fielding medical-related calls from our HMO patients. Since HMO plans paid us a flat rate to take care of them, bringing these patients to the office cost us money and offering these patients medical consults by phone instead, for routine issues, would be more cost-effective for us and a lot more convenient for them.

At that time, the front desk fielded over 500 patient calls a day. I sat next to the four receptionists, and the HMO screened patients with straightforward medical problems would be triaged to me. I then would speak to the patient, review their medical history and address their medical issue and get them what they needed. I was able treat 90% of the screened patients I spoke over the phone, while determining that the other 10% needed face-to-face appointments. During a typical 3.5 hour shift, I routinely spoke to 25 patients, and immediately helped 23 of those patients with their medical issues thereby avoiding an office visit.

Unfortunately, the experiment didn’t last long. To the business managers of the practice, we lost $500 in co-pays while I logged half days on the phone, not billing a single dollar for the practice. Where I saw opportunity and a new paradigm, they saw lost income.

Thus, I returned to my routine day, seeing 25 patients a day in person, day after day. But drudgery of this led to deepening despair. So many unnecessary office visits, patients upset with their delays, apologies for running late, and meetings about how to see more patients, see them faster, charge the insurance companies more. In some cases all the delays had led to a complication that could have been avoided with more timely care.

Not undeterred, I discretely planned a study in 1999. For two weeks I collected data on each patient I saw. Recording data on a laptop during each visit, I analyzed three questions: How long did we talk, how long did the exam take, how often did I already know what to do through history alone and not due to findings from the face-to-face exam.

Here are the results: I saw an average of 23 patients a day. The longest office visit was 45 minutes, and the longest physical examination of a complicated patient took 10 minutes. Sixty-six percent of my patient visits had no reason to be in the office, with my diagnosis relying on patient history and not being influenced by my physical exam.

On reflection of the data, the implication of the data awoke me to a new realization. I must step outside the “Matrix” that I had been a part of: a healthcare system that often delayed and even held hostage 2 of 3 patients I saw each day.

But making the decision to step outside this system was not easy: why should I risk my medical career as I knew it, and my financial security to do what is best for my patients and deliver them the quality they care they needed?

It was my wife, who, in 2001, finally convinced me to move on. She wrote a resignation letter to my medical practice, a practice filled with respected friends and colleagues. As I sat pondering the risk I’d confront by handing in the letter, my wife reminded me of a familiar refrain, “Ships are safe at harbor, but that’s not what ships are for.”

And so, in 2002, I founded doctokr Family Medicine, a practice that does step outside the typical paradigm of healthcare. My patients control how and when they are seen by our medical team. At doctokr, all of the patients establish their care through a face-to- face visit at the office. We gather their history, review their records and do an exam. After that, all established patients are free to email or call the doctor directly, 24/7. Over half of patients’ issues are resolved remotely, via phone or email. Our medical team also sees patients if they want to be seen, or if we feel we need to see them 7 days a week.

As a medical practice with 3000 pioneering patients, we sail on empty oceans but with full faith that we will not have done so in vain. Our experience has shown happier and healthier patients, providers with a mission and passion again and pricing that is 50% less than the current system price of healthcare.

For doctors and patients, staying “safe” behind the many unexamined assumptions in health care makes such harbor risky indeed.

Until next week, I remain yours in primary care,

Alan Dappen, MD