July 14th, 2014 by Dr. Val Jones in Opinion, True Stories

Tags: Benefits, Cancer, Colonoscopy, Guidelines, Harms, Mammogram, Over-testing, Over-treatment, Screening Tests, USPSTF

3 Comments »

Health screening is part of good preventive care, though over-screening can lead to increased costs, and potential patient harm. Healthcare professional societies have recently developed excellent public service announcements describing the dangers of over-testing, and new research suggests that though additional medical interventions are associated with increased patient satisfaction, they also lead (ironically) to higher mortality rates.

Health screening is part of good preventive care, though over-screening can lead to increased costs, and potential patient harm. Healthcare professional societies have recently developed excellent public service announcements describing the dangers of over-testing, and new research suggests that though additional medical interventions are associated with increased patient satisfaction, they also lead (ironically) to higher mortality rates.

And so, in a system attempting to shift to a “less is more” model of healthcare, why is resistance so strong? When the USPSTF recommended against the need for annual, screening mammograms in healthy women (without a family history of breast cancer) between the ages of 40-49, the outcry was deafening. Every professional society and patient advocacy group rallied against the recommendation, and generally not much has changed in the breast cancer screening world. I myself tried to follow the USPSTF guidelines – and opted out of a screening mammogram for two full years past 40. And then I met a charming radiologist at a women’s medical conference who nearly burst into tears when I told her that I hadn’t had a mammogram. Her lobbying for me to “just make sure I was ok” was so passionate that I simply could no longer resist the urge to get screened.

I knew going into the test that there was a reasonably high chance of a false positive result which could cause me unnecessary anxiety. That being said, I was still emotionally unprepared for the radiologists’ announcement that the mammogram was “abnormal” and that a follow up ultrasound needed to be scheduled. I must admit that I did squirm until I had more information. In the end, the “abnormality” proved to be simple “dense breast tissue” and I was pleased to have at least dodged an unnecessary biopsy or lumpectomy. Did my screening do me any good? No, and some psychological harm. A net/net negative but without long term sequelae.

My next personal wrestling match with screening tests was the colonoscopy. I was seeing a gastroenterologist for some GI complaints, and we weren’t 5 minutes into our conversation before he recommended a colonoscopy. I argued that I was too young for a screening colonoscopy (I was 42 and they are recommended starting at age 50), and therefore was doubtful that anything too helpful would be found with the test. My suggestion was that a careful history and some blood testing might be the first place to start. My gastroenterologist acquiesced reluctantly.

As it turns out the blood testing was non-diagnostic and my symptoms persisted so I agreed to the colonoscopy. In this case I felt it was reasonable to do it since it was for diagnostic (not screening) purposes. I was quite certain that it would reveal nothing – or perhaps a false positive followed by anxiety, like my mammogram.

What it did show was some polyps that had a 50% chance of becoming malignant colon cancer in the next 10 years. I was shocked. If I had waited until I was 50 to start screening, I could have missed my cure window. The uneasiness about screening guidelines began to sink in. As a physician I had done my best to apply screening guidelines to myself and resist the urge to over-test, even with a healthy dose of natural curiosity. Yet I failed to resist screening, and in fact, my life was possibly saved by a test that was not supposed to be on my preventive health radar for another 8 years.

Screening tests are recommended for those who are most likely to benefit, and physicians and patients alike are encouraged to avoid unnecessary testing. But there are always a few people outside the “most likely to benefit” pool whose lives could be saved with screening, and the urge to make sure that’s not you – or your patient – is incredibly strong. I’m not sure if that’s human nature, or American culture. But a quick review of Hollywood blockbuster plots (where tens of thousands of lives are regularly sacrificed to save one princess/protagonist/hero from the aliens/monsters/zombies) testifies to our desperately irrational tendencies.

Screening tests are recommended for those who are most likely to benefit, and physicians and patients alike are encouraged to avoid unnecessary testing. But there are always a few people outside the “most likely to benefit” pool whose lives could be saved with screening, and the urge to make sure that’s not you – or your patient – is incredibly strong. I’m not sure if that’s human nature, or American culture. But a quick review of Hollywood blockbuster plots (where tens of thousands of lives are regularly sacrificed to save one princess/protagonist/hero from the aliens/monsters/zombies) testifies to our desperately irrational tendencies.

I am now biased towards over-testing, because my emotional relief at dodging a bullet is stronger than my cerebral desire to adhere to population-based recommendations. Knowing this, I will still try to avoid the temptation to over-test and over-treat my patients. But if they so much as hint that they’d like an early colonoscopy – I will cave.

Does that make me a bad doctor?

July 10th, 2014 by Dr. Val Jones in Opinion, True Stories

Tags: Bad Bedside Manner, Bad Doctors, Colonoscopy, Compassion, Empathy, Gastroenterologist, Lack, Lack of Caring

6 Comments »

I am a regular reader of patient blogs, and I find myself frequently gasping at the mistreatment they experience at the hands of my peers. Yesterday I had the “pleasure” of being a patient myself, and found that my professional ties did not protect me from outrageously poor bedside manners. I suppose I’m writing this partly to vent, but also to remind healthcare professionals what not to do to patients waking up from anesthesia. I also think my experience may serve as a reminder that it’s ok to fire your doctor when conditions warrant.

I am a regular reader of patient blogs, and I find myself frequently gasping at the mistreatment they experience at the hands of my peers. Yesterday I had the “pleasure” of being a patient myself, and found that my professional ties did not protect me from outrageously poor bedside manners. I suppose I’m writing this partly to vent, but also to remind healthcare professionals what not to do to patients waking up from anesthesia. I also think my experience may serve as a reminder that it’s ok to fire your doctor when conditions warrant.

I chose my gastroenterologist based on his credentials and the quality of training and experience listed on Healthgrades.com I had no personal recommendations to rely upon – so I used what I thought was a reasonable method for finding a good local doctor. When I met him for our initial office consultation he seemed rushed and distracted, without genuine curiosity about my complaints, complicated history, or how to help me find the correct diagnosis. I brushed my instincts aside, presuming he was just having a “bad day” and hoping for more time to discuss things fully once a battery of blood tests had been completed.

Sadly, I didn’t have the chance to review the results with him – instead he instructed his nurse to read me the results over the phone and to schedule me for a colonoscopy. I wanted to discuss the pros and cons of the procedure and what he thought he might be able to rule out with the test. He did not provide me with basic informed consent information, nor was he able to articulate medical necessity for the scope. I decided not to have the test, and I didn’t hear another word from him or his office.

Months later my symptoms had worsened and so I decided that a colonoscopy might help to further elucidate the potential cause. I was not able to get through to my doctor via phone, so I scheduled the test via his nursing staff. I planned to be the first patient of the day, so that we would have time to discuss my symptoms and concerns.

On the day of the procedure my physician stormed into my surgical bay and began reading my medical history to me from the computer screen, without exchanging basic niceties or introducing himself to my husband. I confirmed the information and tried to offer some nuance since our last office meeting. He cut me off, and made me feel as if my observations were completely unhelpful and were getting in the way of our scope time. He left in a rush before I felt that he had any clear sense of what we were trying to accomplish or rule out with the procedure.

A jovial anesthesiologist then entered my curtained cubicle, and made genuine human contact with me. He inquired about the reasons for the procedure and expressed appropriate glee regarding my Mallampati grade I airway. I asked him if he would be so kind as to not position me directly on my left shoulder during the procedure as it was exquisitely tender from a recent orthopedic injury. He promised to do his best to protect the injury while I was sedated.

Cut to the endoscopy suite where the gastroenterologist enters with a grumble as the techs bustle around the scope equipment and the anesthesiologist explains the slightly altered positioning for my comfort. As the propofol anesthetic goes into my vein I feel the gastroenterologist push me fully onto my injury as I lose the ability to protest.

After the procedure I’m back in my bay with my husband, groggy but with more pain in my shoulder than anywhere else. The curtain is drawn back with a yank and in marches the GI doc, relaying the unanticipated abnormal findings. I ask (in a slightly slurred tone) for more information, to which he responds in a loud voice, “You’re not going to remember any of this so just be quiet and listen!”

I persist in my attempts to understand the details to which he shouts “Shut up and listen” with increasing decibels. When I say that the findings still don’t explain my symptoms and that I remain perplexed he says that I should “try probiotics.” Finally he leaves the room, not offering any reassurance about the possibility of bowel perforation and stating that we’ll “Just have to wait for the pathology report, and it will take a while because of the July 4th weekend.”

I was dumbfounded, and not just because of my post-anesthetic stupor, but because of the open hostility showed to me by one of my peers. I asked my husband if I was out of line in my questioning and he said that I sounded “like a drunk person” but that the doctor was definitely being “an a**hole.”

As the nurses untangled me from the IV and EKG stickers and rushed me into a wheelchair and out to my husband’s waiting vehicle, all I could say was “Wow, my gastroenterologist was really mean to me.”

The nurses just nodded and suggested that I wasn’t the first to notice that.

As I recover from the whirlwind interaction with the healthcare system, I feel relief and anger. I’m relieved that my GI doc didn’t perforate my bowel and that we accidentally caught some very bad stuff early on, but I’m angry about how I was treated and feel no closer to an explanation for my symptoms than when I started investigating a year ago. My experience was probably fairly typical for many patients dealing with physicians who have lost empathy and compassion. I am sad that there are so many like that out there and I promise to do my best not to follow suit.

My bottom line on gastroenterologists (sorry for the horrible pun): Go with your gut. If your doctor displays jerk-like tendencies during your office visit, rest assured that they can bloom in time. Have the courage to find another doctor before you put your life in their hands and/or they get the chance to verbally abuse you in a post-anesthetic stupor. I am firing my doctor a little bit on the late side, but doing it nonetheless. I just hope that my orthopedist is a good egg (like my anesthesiologist) – because I’ve got one heck of a sore shoulder coming his way!

June 3rd, 2014 by Dr. Val Jones in Health Policy, Opinion

Tags: AHCJ, CMS, EMR, HIPAA, Hospital Quality, Hospital Safety, HospitalInspections.org, Inspectors, Privacy Paperwork, Restraint Orders, Violations, Watch List

6 Comments »

In an effort to promote transparency in healthcare, the Association of Health Care Journalists (AHCJ) has published a database of recent hospital deficiencies discovered by Medicare and Medicaid inspectors. They then highlighted 168 reports containing the phrase “immediate jeopardy.” This, of course, piqued my interest as I presumed that hospitals who were putting putting patients in “immediate jeopardy” must be some pretty bad actors.

In an effort to promote transparency in healthcare, the Association of Health Care Journalists (AHCJ) has published a database of recent hospital deficiencies discovered by Medicare and Medicaid inspectors. They then highlighted 168 reports containing the phrase “immediate jeopardy.” This, of course, piqued my interest as I presumed that hospitals who were putting putting patients in “immediate jeopardy” must be some pretty bad actors.

After sifting through the hospital names, I saw no record of ones who should probably be on the list based on my personal experiences. I did find some surprises, including well respected academic centers (including Stanford, UCSD, and Intermountain Health). I did a “deep dive” on a hospital for which I have a good deal of respect and some familiarity. What I discovered was both funny and sad.

In the case of the hospital that I knew, the very grave concerns expressed by the inspectors turned out to revolve around patient signatures on HIPAA documentation, and physicians refreshing their electronic restraint orders on patients with traumatic brain injuries. These documentation mishaps had landed the hospital on the ominous list of institutions who are “putting patients lives in immediate jeopardy.”

What a waste of inspector time and hospital resources! Apparently, a hospital who passes CMS muster simply means that they are providing documentation correctness to patients. Forget the real sources of life-threatening dangers – medication errors, poor physician handoffs, unnecessary testing and treatment, and unsanitary conditions. What the safety police are focused upon is whether or not the sick and delirious signed their health information privacy paperwork.

Now don’t get me wrong, I think it’s important to let patients know their rights, etc. But I’ve yet to see more than 10% of patients even read the HIPAA-related documentation that they sign. Surely an absent signature or two shouldn’t land a hospital on a humiliating federal watch list.

True patient safety cannot be regulated. It is far too complex and nuanced, requiring collaboration between all members of a hospital’s staff. From frequent nursing surveillance, to careful medication review, to laboratory critical value alerts, to conscientious sanitation practices – hospital culture dictates whether or not a patient receives excellent care. Watch lists would be far more accurate if they were simply based on hospital employee questionnaires. As Dr. Marty Makary has discovered, complicated care quality algorithms are no more accurate at predicting hospital excellence than simply asking staff if they’d recommend the place to family members.

So next time you see your hospital flagged by the feds, don’t assume that there is a serious problem going on – better to ask someone who works there if it’s a safe place for care.

May 29th, 2014 by Dr. Val Jones in Health Policy, Opinion

Tags: CompHealth, Ethics, healthcare, Jobs, Locum Tenens, Matching, MSP, Negative, Nurses, Physicians, Privacy, Problems, Quality, Staffing Agency, Vendor Management System, VMS

4 Comments »

In an effort to save on human resources costs, some hospitals have decided to make locum tenens* doctors and nurses line items in a supply list. Next to IV tubing, liquid nutritional supplements and anti-bacterial wipes you’ll find slots for nurses, surgeons, and hospitalist positions. This depressing commoditization of professional staffing is a new trend in healthcare promoted by software companies promising to solve staffing shortages with vendor management systems (VMS). In reality, they are removing the careful provider recruiting process from job matching, causing a “race to the bottom” in care quality. Instead of filling a staff position with the most qualified candidates with a proven track record of excellent bedside manner and evidence-based practice, physicians and nurses with the lowest salary requirements are simply booked for work.

In an effort to save on human resources costs, some hospitals have decided to make locum tenens* doctors and nurses line items in a supply list. Next to IV tubing, liquid nutritional supplements and anti-bacterial wipes you’ll find slots for nurses, surgeons, and hospitalist positions. This depressing commoditization of professional staffing is a new trend in healthcare promoted by software companies promising to solve staffing shortages with vendor management systems (VMS). In reality, they are removing the careful provider recruiting process from job matching, causing a “race to the bottom” in care quality. Instead of filling a staff position with the most qualified candidates with a proven track record of excellent bedside manner and evidence-based practice, physicians and nurses with the lowest salary requirements are simply booked for work.

In a policy environment where quality measures and patient satisfaction ratings are becoming the basis for reimbursement rates, one wonders how VMS software is getting traction. Perhaps desperate times call for desperate measures, and the challenge of filling employment gaps is driving interest in impersonal digital match services? Rural hospitals are desperate to recruit quality candidates, and with a severe physician shortage looming, warm bodies are becoming an acceptable solution to staffing needs.

As distasteful as the thought of computer-matching physicians to hospitals may be, the real problems of VMS systems only become apparent with experience. After discussing user experience with several hospital system employees and reading various blogs and online debates here’s what I discovered:

1. Garbage In, Garbage Out. The people who input physician data (including their certifications, medical malpractice histories, and licensing data) have no incentive to insure accuracy of information. Head hunter agencies are paid when the physicians/nurses they enter into the database are matched to a hospital. To make sure that their providers get first dibs, they may leave out information, misrepresent availability, and in extreme cases, even falsify certification statuses. These errors are often caught during the hospital credentialing process, which results in many hours of wasted time on the part of internal credentialing personnel, and delays in filling the position. In other cases, the errors are not caught during credentialing and legal problems ensue when impaired providers are hired accidentally.

2. Limitation of choice. The non-compete contracts associated with VMS systems typically prevent hospital physician recruiters from contacting staffing agencies directly to fill their needs. This forces the hospital to rely on the database for all staffing leads. At least 68% of staffing agencies do not participate with VMS systems, so a large portion of the most carefully vetted professionals remain outside the VMS, inaccessible to those who contracted to use it.

3. Extra hospital employee training required. There are hundreds of proprietary VMS systems in use. Each one requires specialized training to manage everything from durable medical equipment to short term surgical staff. In cases where hospital staff are spread too thin to master this training, some VMS companies are pleased to provide a “managed service provider” or MSP to outsource the entire recruitment process. This adds additional layers, further removing the hospital recruiter from the physician.

4. Providers hate VMS systems. As anyone who has read a recent nursing blog can attest, VMS systems are universally despised by the potential employees they represent. VMS paints professionals in black and white, without the ability to distinguish quality, personality, or perform careful reference checks. They force down salaries, may rule out candidates based on where they live (travel costs), and provide no opportunity to negotiate salary vis-a-vis work load. When a hospital opts to use a VMS system as a middle man between them and the staffing agencies, the agencies often pass along the cost to the providers by offering them a lower hourly rate.

5. Provider privacy may be compromised. Once a physician or nurse curriculum vitae (CV) is entered into the VMS database the agency recruiter who entered it has 1 year (I can’t confirm that this is true for all systems) to represent them exclusively. After that, the CV is often available for any recruiter who has access to that VMS to view or pitch to any client. There is a wide variety of agency quality in the healthcare staffing industry, with some being highly ethical and selective in choosing their clients (only quality hospitals) and providers (carefully screened). Others are transactional, bottom-feeders with all the scruples of a used car salesman. When your data is in a VMS, one minute you might be represented by a caring, thoughtful recruiter who understands and respects your career needs, and the next (without your informed consent) you’ll be matched to a bankrupt hospital undergoing investigation by the Department of Health by a gum-chewing salesman who threatens you with a lawsuit if you don’t complete an assignment for half the pay you usually receive.

6. No cost savings, only increased liability. In the end, some hospitals who have tried VMS systems say that their decreased hiring costs have not resulted in overall savings. While they may see a downward shift in salary paid to their temporary work force, they get what they pay for. Just one “bad hire” who causes a medical malpractice lawsuit can eat up salary savings for an entire year of VMS. Not to mention the increased costs associated with a slower hiring process, attrition from poor fits, and the inconvenience of having to re-recruit for positions over and over again. Providers also lose out on career opportunities while they’re “on hold” during a prolonged hiring process. And for those who layer on a MSP, they lose control of the most important hospital quality and safety line of defense – choosing your own doctors and nurses.

In summary, while the idea of using a software matching service for recruiting physicians and nurses to hospitals sounds appealing at first, the bottom line is that reducing care providers to a group of numerical fields removes all the critical nuance from the hiring process. VMS, with their burdensome non-competes, cumbersome technology, and lack of quality control are an unwelcome new middle man in the healthcare staffing environment. It is my hope that they will be squeezed out of the business based on their own inability to provide value to a healthcare system that craves and rewards quality and excellence in its staff.

Job matching requires thoughtful hospital recruiters in partnership with ethical, experienced agencies. Choosing one’s hospital gauze vendor should involve a different selection algorithm than hiring a new chief of surgery. It’s time for physician and nurse groups to take a stand against this VMS-inspired commoditization of medicine before its roots sink in too deeply and we all become mere line items on a hospital vendor list. So next time you doctors and nurses plan to work a temporary assignment, ask your recruiter if they use a VMS system. Avoiding those agencies who do may mean a much better (and higher paying) work experience.

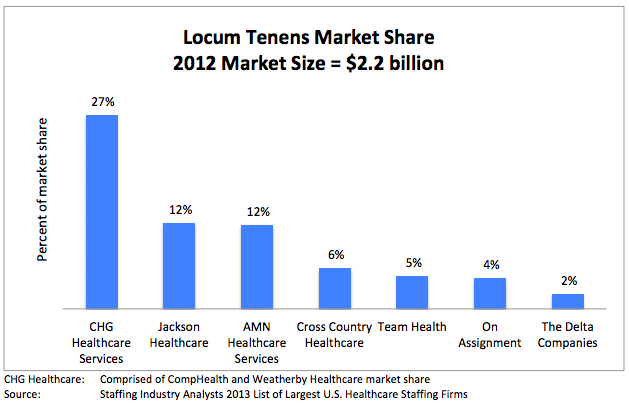

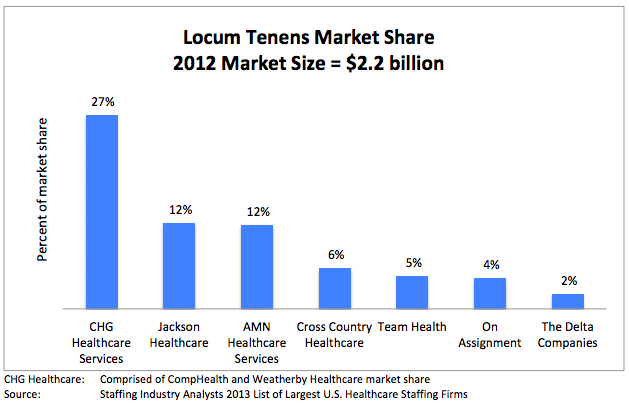

*Locum tenens (filling hospital staffing needs with part time or traveling physicians and nurses) is big business. Here is a run down of the estimated market size and its key industry leaders (provided by CompHealth):

May 5th, 2014 by Dr. Val Jones in Expert Interviews, Health Policy, Opinion

Tags: Anesthesiologists, Freedom, Hospitalists, ICU, Intensivists, Job satisfaction, Locum Tenens, Physicians, Temp Work

1 Comment »

It’s no secret that most physicians are unhappy with the way things are going in healthcare. Surveys report high levels of job dissatisfaction, “burn out” and even suicide. In fact, some believe that up to a third of the US physician work force is planning to leave the profession in the next 3 years – an alarming statistic.

It’s no secret that most physicians are unhappy with the way things are going in healthcare. Surveys report high levels of job dissatisfaction, “burn out” and even suicide. In fact, some believe that up to a third of the US physician work force is planning to leave the profession in the next 3 years – an alarming statistic.

Direct primary care practices are touted as the best way to restore patient and provider satisfaction. Those brave enough to cut out the “middle man” (i.e. health insurers, both public and private) find a remarkable reduction in billing paperwork, unrecovered fees, and electronic documentation requirements. I know many physicians who have made the switch and are extremely happy to be able to spend most of their time in direct patient care, unfettered by most rules, regulations, and coding systems. They can solve problems via phone, email, text, video chat, or in-office as the need arises without having to worry about whether or not their manner of interaction will be reimbursed.

Direct primary care is probably the best way to find freedom and happiness in practicing outpatient medicine. But where does that leave physicians who are tied to hospital care due to the nature of their specialty (surgeons, intensivists, anesthesiologists, etc.)? Is there any way for them to find a brighter way forward?

I have found that working as a locum tenens hospital-based physician has dramatically improved my work satisfaction, and it may do so for you too. Here’s why:

1. You can take as much time off as you want, anytime you want. Do not underestimate the power of frequent vacations on your mental health. The frenetic pace of the hospital is much more tolerable in short doses. My attitude, stamina, and ability to stay focused is dramatically improved by working only 2-3 week stretches at a time. When I feel good, I can spread the cheerfulness, and I am happy to spend longer hours at work to give my patients more of my time.

2. You can avoid most political drama. Hospitals are incredibly stressful environments filled with hierarchical and territorial land mines. Being a short-timer allows you to avoid many conflicts. Administrators never nag you, or hold you responsible for perceived departmental deficiencies. You don’t need to attend committee meetings or become involved in personality quirk arbitrage. You can stay above the fray, focusing purely on the patients.

3. You learn all kinds of new things. Exposure to different patient populations, hospital expertise and different peer groups exposes you to a broader swath of technology and humanity. No longer will you be tied to the regional practice idiosyncrasies of a single hospital – you’ll learn how to tackle problems from many different angles. That knowledge earns you respect, and serves to cross-pollinate your own specialty, making you – and those you learn from – better doctors.

4. You are free to leave. There’s something refreshing about knowing that you can leave a place that you don’t like without any repercussions. No matter how unpleasant a locums assignment, it will end, and you can saunter off to brighter pastures.

5. You make more money. Believe it or not, locums work can be quite lucrative if you find the right assignments. I know a team of hospitalists who travel the country together, negotiating higher rates since they are a “one stop” solution. Their housing, travel, and cars are paid for by the agency, and they have take home pay (before taxes) around $350K per year. I personally think that working that many hours as a locum tenens physician kind of defeats the purpose of avoiding burn out, but some people like to do it that way.

6. You can live in the warm states in the winter, and the cold ones in the summer. Enough said.

7. You can try before you buy. Maybe you’re not sure where you want to sink down career roots. Or maybe you’re not sure you’ll like living in a certain city or part of the world? Maybe your family isn’t sure they want to move to a new location? Locum tenens assignments are the perfect way to try before you buy.

8. You can use your experience to become an excellent consultant. With long term exposure to various hospital systems, you are in a unique position to develop an encyclopedic knowledge of best practices. Sharing how other hospitals have solved their challenges can spark reform at other institutions. You can become a real force for positive change, not just on a micro level, but system and state-wide.

Working as a locum tenens physician may enhance your career satisfaction and promote professional advancement. What it will not solve, however, is the following:

1. You still have to work within the framework of bureaucracy endemic to hospitals. You’ll need to learn to use multiple different EMR systems and fill out most of the same paperwork that you do as a full-timer. This is painful at first, but once you’ve mastered the most common EMR systems (I’ve only really encountered 5 different ones in 2 years of locum tenens work) you’ll find a clinical rhythm that fits into most frameworks.

2. You will be living out of a suitcase. If the disruption of frequent travel is too much for you (or your family) to bear, then perhaps the locums lifestyle is not for you.

3. You will be annoyed by the process of getting multiple medical licenses and hospital credentialing. Agencies try to help with this burden, but mostly, you’ll need to suffer through this part yourself.

4. You will have to live with some degree of uncertainty. Part of the nature of working as a locum tenens physician is that clients (hospitals) change their minds frequently. They try to fill open positions with local staff or hire additional full-timers, using locums as their more expensive back ups. Assignments fall through frequently, so you’ll need to be ready to change course quickly.

Overall, I believe that locum tenens work can provide the practice freedom that many hospital-based physicians crave. If you’re eager to get off the unrelenting clinical treadmill, this is an easy way to do it. At a recent assignment near New Hampshire, I mused at the license plates that I passed on my way to work: “Live free or die” is their state motto. And I think it captures my sentiments exactly.

Health screening is part of good preventive care, though over-screening can lead to increased costs, and potential patient harm. Healthcare professional societies have recently developed excellent public service announcements describing the dangers of over-testing, and new research suggests that though additional medical interventions are associated with increased patient satisfaction, they also lead (ironically) to higher mortality rates.

Health screening is part of good preventive care, though over-screening can lead to increased costs, and potential patient harm. Healthcare professional societies have recently developed excellent public service announcements describing the dangers of over-testing, and new research suggests that though additional medical interventions are associated with increased patient satisfaction, they also lead (ironically) to higher mortality rates. Screening tests are recommended for those who are most likely to benefit, and physicians and patients alike are encouraged to avoid unnecessary testing. But there are always a few people outside the “most likely to benefit” pool whose lives could be saved with screening, and the urge to make sure that’s not you – or your patient – is incredibly strong. I’m not sure if that’s human nature, or American culture. But a quick review of Hollywood blockbuster plots (where tens of thousands of lives are regularly sacrificed to save one princess/protagonist/hero from the aliens/monsters/zombies) testifies to our desperately irrational tendencies.

Screening tests are recommended for those who are most likely to benefit, and physicians and patients alike are encouraged to avoid unnecessary testing. But there are always a few people outside the “most likely to benefit” pool whose lives could be saved with screening, and the urge to make sure that’s not you – or your patient – is incredibly strong. I’m not sure if that’s human nature, or American culture. But a quick review of Hollywood blockbuster plots (where tens of thousands of lives are regularly sacrificed to save one princess/protagonist/hero from the aliens/monsters/zombies) testifies to our desperately irrational tendencies.

I am a regular reader of patient blogs, and I find myself frequently gasping at the mistreatment they experience at the hands of my peers. Yesterday I had the “pleasure” of being a patient myself, and found that my professional ties

I am a regular reader of patient blogs, and I find myself frequently gasping at the mistreatment they experience at the hands of my peers. Yesterday I had the “pleasure” of being a patient myself, and found that my professional ties  In an effort to promote transparency in healthcare, the Association of Health Care Journalists (AHCJ) has published a database of recent hospital deficiencies discovered by Medicare and Medicaid inspectors. They then highlighted

In an effort to promote transparency in healthcare, the Association of Health Care Journalists (AHCJ) has published a database of recent hospital deficiencies discovered by Medicare and Medicaid inspectors. They then highlighted  In an effort to save on human resources costs, some hospitals have decided to make locum tenens* doctors and nurses line items in a supply list. Next to IV tubing, liquid nutritional supplements and anti-bacterial wipes you’ll find slots for nurses, surgeons, and hospitalist positions. This depressing commoditization of professional staffing is a new trend in healthcare promoted by software companies promising to solve staffing shortages with vendor management systems (VMS). In reality, they are removing the careful provider recruiting process from job matching, causing a “race to the bottom” in care quality. Instead of filling a staff position with the most qualified candidates with a proven track record of excellent bedside manner and evidence-based practice, physicians and nurses with the lowest salary requirements are simply booked for work.

In an effort to save on human resources costs, some hospitals have decided to make locum tenens* doctors and nurses line items in a supply list. Next to IV tubing, liquid nutritional supplements and anti-bacterial wipes you’ll find slots for nurses, surgeons, and hospitalist positions. This depressing commoditization of professional staffing is a new trend in healthcare promoted by software companies promising to solve staffing shortages with vendor management systems (VMS). In reality, they are removing the careful provider recruiting process from job matching, causing a “race to the bottom” in care quality. Instead of filling a staff position with the most qualified candidates with a proven track record of excellent bedside manner and evidence-based practice, physicians and nurses with the lowest salary requirements are simply booked for work.

It’s no secret that most

It’s no secret that most