February 14th, 2010 by Davis Liu, M.D. in Better Health Network, News, Opinion

No Comments »

While the news reports that Representative John Murtha of Pennsylvania died after complications from gallbladder surgery, the question no one is asking is whether his death was a preventable one or simply an unfortunate outcome. According to the Washington Post, Murtha had elective laproscopic gallbladder surgery performed at the Bethesda Naval Hospital and fell ill shortly afterwards from an infection related to his surgery.

He was hospitalized to Virginia Hospital Center in Arlington, Virginia, to treat the post-operative infection. His care was being monitored in the intensive care unit (ICU), a sign which suggests that not only was the infection becoming widespread but also that vital organ systems were shutting down. Read more »

*This blog post was originally published at Saving Money and Surviving the Healthcare Crisis*

June 29th, 2009 by EvanFalchukJD in Better Health Network, Health Policy

No Comments »

Everything is McAllen, Texas.

It’s all part of our “uniquely American” approach to many issues: oversimplify the problem, so we can solve it. Ideally, on an artificially short time line.

In the case of health care reform, let’s say we get ‘er done by August 1.

When we talk about health care reform, we are really talking about dozens of different issues. Is health care reform about covering the uninsured, or about cutting costs for employers? Is it about having a publicly-funded health plan, or changing reimbursements to doctors? Is it about longer life expectancies or creating insurance cooperatives? Is it about caps on medical malpractice awards, or comparative effectiveness? Is it about healthier lifestyles, or cutting the cost of prescription drugs? Is it about cutting administrative waste, or incentives for more people to go to medical school? Is it about implementing new health care IT, or preventing insurers from making excessive profits?

It’s about all of these things, and more. And that’s the problem, if you’re an ambitious reformer. There is no simple way to get all of these things under one roof.

Well, until Atul Gawande introduced us to McAllen.

The President quickly made Dr. Gawande’s article on McAllen required reading at the White House, telling Senators this is the problem we are trying to solve. His point man on health care, Peter Orszag, has been blogging about it repeatedly. Members of Congress and the press have taken to talking about McAllen as the center of the health care debate. Even doctors from McAllen are calling on the President to come and see for himself.

Others are using it, too. Paul Krugman, in his blog, took on Harvard economist Greg Mankiw for saying that some comparisons of the US and foreign health care systems may be flawed as a premise for U.S. reform. In response Krugman said “read Atul Gawande!” I saw this, too, when I questioned Steven Pearlstein about why he had such a problem with doctors. His only response was “Maybe you should talk to Atul.”

The problems of McAllen make easy talking points. But they are also a convenient way of avoiding dealing with the enormous complexity of the health care system. There are nearly 650,000 doctors in America, millions of patients, thousands of hospitals, tens of thousands of insurance and pharmaceutical companies, hundreds of thousands of employers who provide health benefits, and thousands of other charities, academics, consultants, government agencies and others who have strongly held views about our system. Too often, their voices are not being heard in all the loud talking about McAllen.

And so, if reforming our health care system is, as the President says, a “moral imperative,” why can’t we have a process that treats reform that way? Why the rush to pass reforms that have to be sold under the premise of solving the problems of McAllen?

The President and the Congress are perfectly capable of putting together a respected commission of experts to study health care, in depth, and then return with serious, comprehensive recommendations that Congress and the President can work to enact. Polls show great public support for the idea of reform, but mixed understanding on what reform means. As we see from the evaporating support for reform in Congress, this gap is a serious problem.

We need effective health care reform in America. McAllen isn’t enough to close the deal.

*This blog post was originally published at See First Blog*

June 14th, 2009 by EvanFalchukJD in Better Health Network, Health Policy

4 Comments »

Everyone is reading Atul Gawande’s article in the New Yorker about health care costs. But I think most people misunderstand Gawande’s major point.

Everyone’s At It

The conventional wisdom on Gawande’s piece is this: our problems are caused by bad incentives in our health care system. They encourage doctors to overprescribe care. McAllen, Texas is the poster child of this problem. If we can change the economic incentives, doctors will behave better. They will follow medical evidence, not their bottom lines, and from this will emerge a rational, affordable system.

This isn’t what Gawande is saying.

Gawande went to McAllen expecting to see a microcosm of the American health care system. As expected, he found excessive, even abusive spending, and a culture that encouraged both. But he also found that in nearby El Paso, Texas, medicine wasn’t practiced this way, nor in most other places in the country. And so he came up with a surprising insight. Yes, McAllen is a reflection of what can happen based on the incentives in the system. But if every incentive works this way, why is McAllen such an outlier?

Gawande concluded it had to do with the “culture” of medicine in each community. Most doctors go into medicine to help patients. In Gawande’s visit to McAllen, he heard stories that money had become more important than quality care. What Gawande realized was how important this question of “culture” was to how McAllen became McAllen. It made him think of places that had a completely different culture, like the Mayo Clinic.

The doctors of the Mayo Clinic decided, some decades ago, to put medicine first:

The core tenet of the Mayo Clinic is “The needs of the patient come first” — not the convenience of the doctors, not their revenues. The doctors and the nurses, and even the janitors, sat in meetings almost weekly, working on ideas to make the service and the care better, not to get more money out of patients. . . . Mayo promoted leaders who focused first on what was best for patients, and then on how to make this financially feasible.

Gawande couldn’t believe how much time doctors at the Mayo clinic spent with each patient, and how readily they could interact with colleagues on difficult problems. While it is true, the Mayo Clinic has financial arrangements that make this easier, it is the culture of patient care that dominates, not questions of pay:

No one there actually intends to do fewer expensive scans and procedures than is done elsewhere in the country. The aim is to raise quality and to help doctors and other staff members work as a team. But almost by happenstance, the result has been lower costs.

“When doctors put their heads together in a room, when they share expertise, you get more thinking and less testing,” [Denis] Cortes [CEO of the Mayo Clinic] told me

And this is where Gawande is being misunderstood.

The “cost conundrum” that Gawande talks about is not about how to cut costs, or how to change who pays for health care and how much. It’s deeper than that. Gawande’s point is that we have been fixated for so long on the question of money in health care that we are starting to forget about medicine. By focusing on ever more clever ways to pay doctors, we have systematically undervalued everything that makes for high quality medicine. Things like time with your patient, thinking about his or her problems, consulting with colleagues, and coming up with sound advice.

We discount what he calls the “astonishing” accomplishments of the Mayo Clinic on this score. And instead of designing health care reform around ways to help more hospitals become like the Mayo Clinic, we choose instead to think about money, to focus our attention on how to cut costs in places like McAllen.

Politically, it makes sense – it’s convenient to have a poster child like McAllen to explain why one reform plan or another should become law. But the pity is that in this important time of reform we’re not talking about trying to put the needs of the patients first – to put medicine back in the center of health care. The pity is that in spite of the fact that everyone’s reading Gawande’s article, his most important insight is being misunderstood.

If we continue to be focused on money over medicine, we will lose the “war over the culture of medicine – the war over whether our country’s anchor model with be Mayo or McAllen.”

*This blog post was originally published at See First Blog*

June 13th, 2009 by Shadowfax in Better Health Network, Health Policy

No Comments »

Ezra opines a bit on the role of doctors in health care with the strangely misleading headline:

Listen to Atul Gawande: Insurers Aren’t the Problem in Health Care

This wasn’t Gawande’s point at all, and is something quite tangential to Klein’s point:

The reason most Americans hate insurers is because they say “no” to things. “No” to insurance coverage, “no” to a test, “no” to a treatment. But whatever the problems with saying “no,” what makes our health-care system costly is all the times when we say “yes.” And insurers are virtually never the ones behind a “yes.” They don’t prescribe you treatments. They don’t push you towards MRIs or angioplasties. Doctors are behind those questions, and if you want a cheaper health-care system, you’re going to have to focus on their behavior.

Yes, doctors are a driver — one of many — in the exponentially increasing cost of health care. Utilization is uneven, not linked to quality or outcomes in many cases, and may often be driven by physicians’ personal economic interests. All of this is not news, though certainly Atul Gawande wove it together masterfully in his recent New Yorker article. (I’m assuming you’ve all read it — If not, then stop reading this drivel and go read it immediately.) Nobody disputes that doctors’ behavior (and ideally their reimbursement formula) need to change if effective cost control will be brought to bear on the system.

But it’s completely off-base to claim that insurers aren’t one of the problems in the current system. There are two crises unfolding in American health care — a fiscal crisis and an access crisis. I would argue that insurers are less significant as a driver of cost than they are as a barrier to access. Overall, insurers have, I think, only a marginal effect on cost growth, largely due to the friction they introduce to the system — paperwork, hassles & redundancy and internal costs such as executive compensation, advertising and profits. It would be great if this could be reduced, but it wouldn’t fix the escalation in costs, only defer the crisis for a few years until cost growth caught up to today’s level. In the wonk parlance, it wouldn’t “bend the cost curve,” just step it down a bit.

But as for access to care, insurers are the biggest problem. It’s not their “fault” per se in that they are simply rational actors in the system as it’s currently designed. Denying care, rescinding policies, aggressive underwriting and cost-shifting are the logical responses of profit-making organizations to the market and its regulatory structure. Fixing this broken insurance system will not contain costs, but it will begin to address the human cost of the 47 million people whose only access to health care is to come to see me in the ER.

*This blog post was originally published at Movin' Meat*

November 8th, 2008 by Dr. Val Jones in Celebrity Interviews, Expert Interviews

8 Comments »

|

|

Dr. Gawande

|

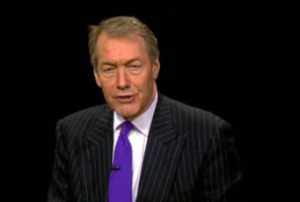

Kaiser Permanente sponsored a special event in DC today – Charlie Rose interviewed Dr. Atul Gawande about patient safety in front of an audience of physicians. Dr. Gawande is a young surgeon at Harvard’s Dana Farber Cancer Institute, has written two books about performance improvement, and is a regular contributor to the New Yorker magazine. I had heard many positive things about Atul, but had never met him in person. I was pleasantly impressed.

Atul strikes me as a genuinely humble person. He shifted uncomfortably in his chair as Charlie Rose cited a long list of his impressive accomplishments, including writing for the New Yorker. Atul responded:

I’m not sure how my writing became so popular. I took one fiction-writing class in college because I liked a girl who was taking the class. I got a “C” in the class but married the girl.

He went on to explain that because his son was born with a heart defect (absent aortic arch) he knew what it felt like to be on the patient side of the surgical conversation. He told the audience that at times he felt uncomfortable knowing which surgeons would be operating on his son, because he had trained with them as a resident, and remembered their peer antics.

Atul explained that patient safety is becoming a more and more complicated proposition as science continues to uncover additional treatment options.

If you had a heart attack in the 1950’s, you’d be given some morphine and put on bed rest. If you survived 6 weeks it was a miracle. Today not only do we have 10 different ways to prevent heart attacks, but we have many different treatment options, including stents, clot busters, heart surgery, and medical management. The degree of challenge in applying the ultimate best treatment option for any particular patient is becoming difficult. This puts us at risk for “failures” that didn’t exist in the past.

In an environment of increasing healthcare complexity, how do physicians make sure that care is as safe as possible? Atul suggests that we need to go back to basics. Simple checklists have demonstrated incredible value in reducing central line infections and surgical error rates. He cited a checklist initiative started by Dr. Peter Pronovost that resulted in reduction of central line infections of 33%. This did not require investment in advanced antibacterial technology, and it cost almost nothing to implement.

Atul argued that death rates from roadside bombs decreased from 25% (in the Gulf War) to 10% (in the Iraq war) primarily because of the implementation of check lists. Military personnel were not regularly wearing their Kevlar vests until it was mandated and enforced. This one change in process has saved countless lives, with little increase in cost and no new technology.

I asked Atul if he believed that (beyond check lists) pay for performance (P4P) measures would be useful in improving quality of care. He responded that he had not been terribly impressed with the improvements in outcomes from P4P initiatives in the area of congestive heart failure. He said that because there are over 13,000 different diseases and conditions, it would be incredibly difficult to apply P4P to each of those. He said that most providers would find a way to meet the targets – and that overall P4P just lowers the bar for care.

Non-punitive measures such as check lists and applying what we already know will go a lot farther than P4P in improving patient safety and quality of care.

Atul also touted the importance of transparency in improving patient safety and quality (I could imagine my friend Paul Levy cheering in the background). In the most touching moment of the interview, Atul reflected:

As a surgeon I have a 3% error rate. In other words, every year my work harms about 10-12 patients more than it helps. In about half of those cases I know that I could have done something differently. I remember the names of every patient I killed or permanently disabled. It drives me to try harder to reduce errors and strive for perfection.

Atul argued that hospitals’ resistance to transparency is not primarily driven by a fear of lawsuits, but by a fear of the implications of transparency. If errors are found and publicized, then that means you have to change processes to make sure they don’t happen again. Therein lies the real challenge: knowing what to do and how to act on safety violations is not always easy.

|

|

Charlie Rose

|

Charlie Rose asked Atul the million dollar question at the end of the interview, “How do we fix healthcare?” His response was well-reasoned:

First we must accept that any attempt to fix healthcare will fail. That’s why I believe that we should try implementing Obama’s plan in a narrow segment of the population, say for children under 18, or for laid off autoworkers, or for veterans returning from Iraq. We must apply universal coverage to this subgroup and then watch how it fails. We can then learn from the mistakes and improve the system before applying it to America as a whole. There is no perfect, 2000 page healthcare solution for America. I learned that when I was working with Hillary Clinton in 1992. Instead of trying to fix our system all at once, we should start small and start now. That’s the best way to learn from our mistakes.