April 7th, 2017 by Dr. Val Jones in Opinion

1 Comment »

Over 1 million virtual doctor visits were reported in 2015. Telehealth companies have long asserted that increased access to physicians via video or phone conferencing saves money by reducing office visits and Emergency Department care. But a new study calls this cost savings into question. Increased convenience can increase utilization, which may improve access, but not reduce costs.

Over 1 million virtual doctor visits were reported in 2015. Telehealth companies have long asserted that increased access to physicians via video or phone conferencing saves money by reducing office visits and Emergency Department care. But a new study calls this cost savings into question. Increased convenience can increase utilization, which may improve access, but not reduce costs.

The study has some obvious limitations. First of all, it followed patients who used one particular telehealth service for one specific cluster of disease (“respiratory illness”) and narrowed the cost measure to spending on that condition only. Strep throat, coughs, and sinusitis are not drivers of potentially expensive care to begin with, so major cost savings (by avoiding the ER or hospitalization) would not be expected with the use of telehealth services for most of these concerns.

Secondly, the patients whose data were scrutinized had commercial insurance (i.e. a generally healthier and younger population than Medicare beneficiaries, for example), and it is possible that the use of telehealth would differ among people with government insurance, high-deductible plans or no insurance at all.

Thirdly, the study did not look at different ways that virtual doctor visits are currently being incorporated into healthcare delivery systems. For example, I was part of a direct primary care practice in Virginia (DocTalker Family Medicine) that offered virtual visits for those patients who had previously been examined in-person by their physician. The familiarity significantly reduced liability concerns and the tendency for over-testing. Since the doctor on the other side of the phone or video knew the patient, the differential diagnosis shrank dramatically, allowing for personalized real-time treatment options.

I’ve also been answering questions for eDocAmerica for over 10 years. This service offers employers a very low cost “per member per month” rate to provide access to board-certified physicians who answer patient questions 24/7 via email. eDocs do not treat patients (no ordering of tests or writing prescriptions), but can provide sound suggestions for next steps, second opinions, clarifying guidance on test results, and identify “red flag” symptoms that likely require urgent attention.

For telehealth applications outside the direct influence of health insurance (such as DocTalker and eDocAmerica), cost savings are being reaped directly by patients and employers. The average DocTalker patient saves thousands a year on health insurance premiums (purchasing high deductible, catastrophic plans) and using health savings account (HSA) funds for their primary care needs. They might spend $300/year on office or virtual visits and low-cost lab and radiology testing (pre-negotiated by DocTalker with local vendors). As for eDocAmerica, employers pay less than a dollar per month for their employees to have unlimited access to physician-driven information.

The universe of telehealth applications is larger than we think (including mobile health, remote patient monitoring, and asynchronous data sharing), and already extends outside of the traditional commercial health insurance model. Technology and market demand are fueling a revolution in how we access outpatient healthcare (which represents ~40% of total healthcare costs), making it more convenient and affordable. As these solutions become more commonplace, I have hope that we can indeed dramatically reduce costs and improve access to basic care.

Keeping people well and out of the hospital should be healthcare’s prime directive. When those efforts fail, safety net strategies are necessary to protect patients from devastating costs. How best to provide that medical safety net is one of the greatest dilemmas of our time. For now, we may have to settle for solving the “lower hanging fruit” of outpatient medicine, beginning with expanding innovative uses of telehealth services.

January 26th, 2015 by Dr. Val Jones in Health Policy, Opinion

53 Comments »

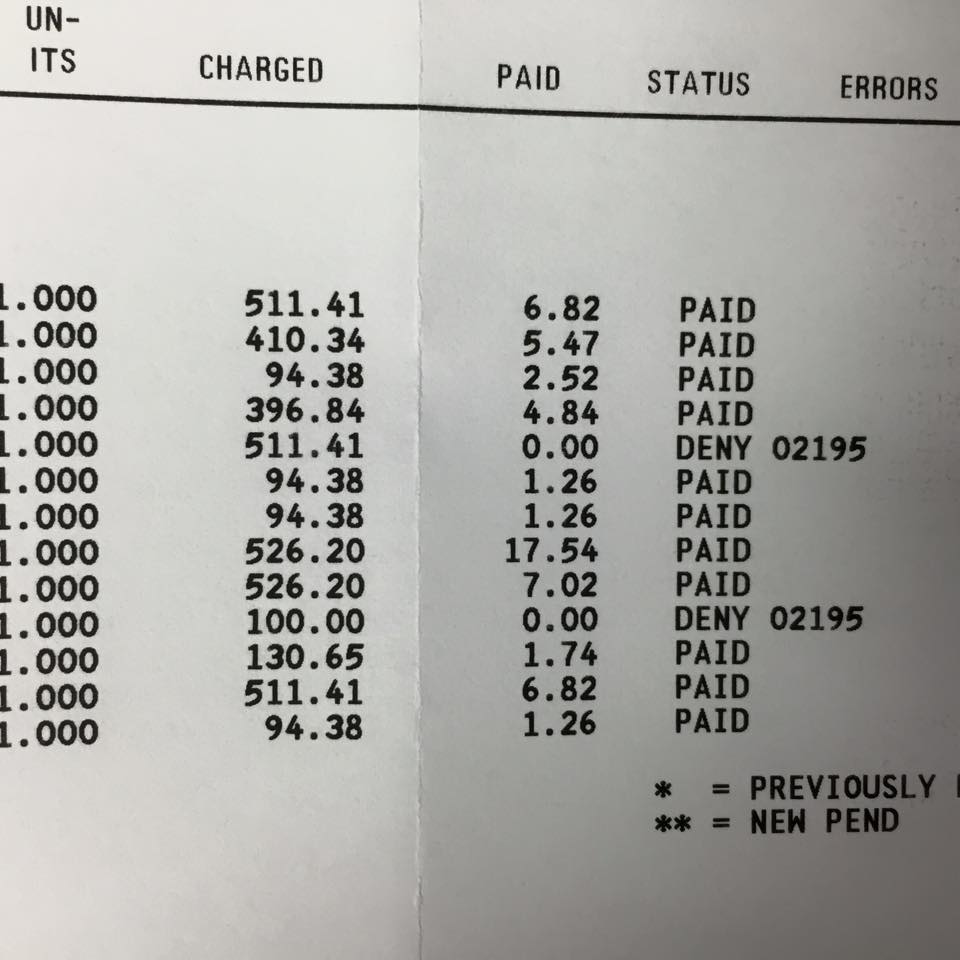

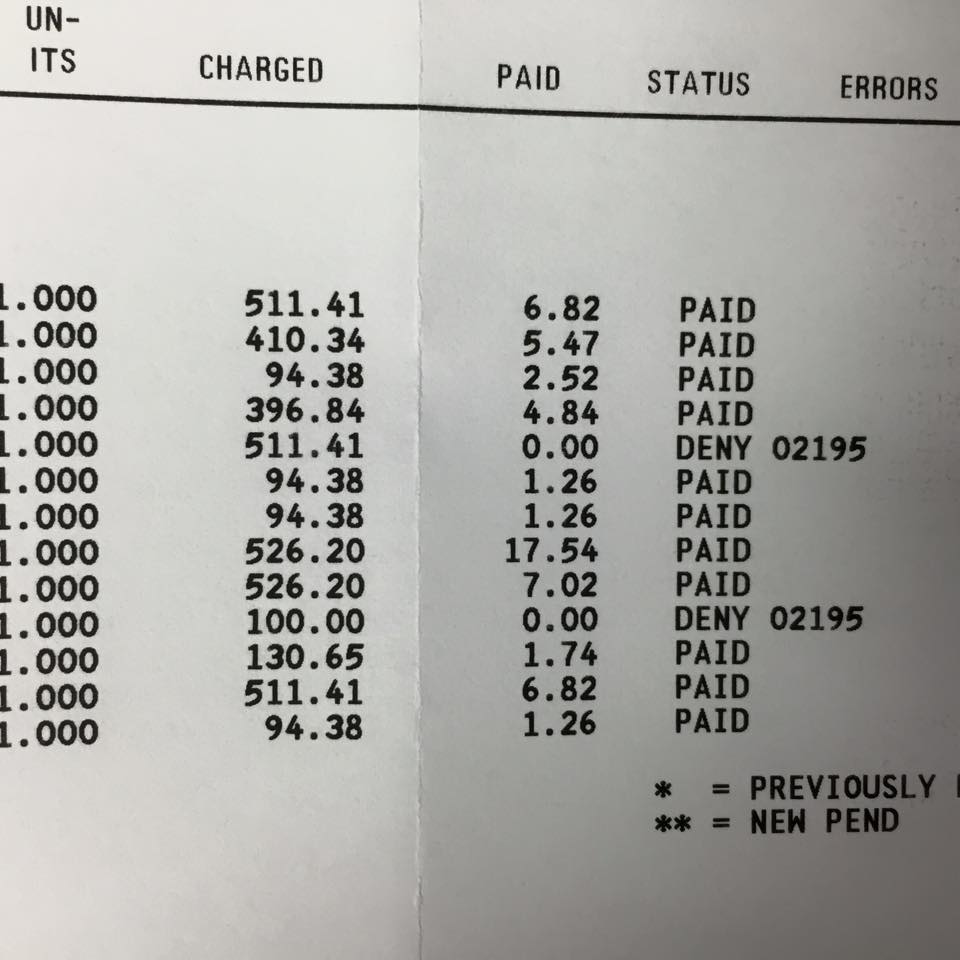

A physician friend of mine posted a copy of her Medicaid reimbursement on Facebook. Take a look at the charges compared to the actual reimbursement. She is paid between $6.82 and $17.54 for an hour of her time (i.e. on average, she makes less than minimum wage when treating a patient on Medicaid).

A physician friend of mine posted a copy of her Medicaid reimbursement on Facebook. Take a look at the charges compared to the actual reimbursement. She is paid between $6.82 and $17.54 for an hour of her time (i.e. on average, she makes less than minimum wage when treating a patient on Medicaid).

The enthusiasm about expanding Medicaid coverage to the previously uninsured seems misplaced. Improved “access” to the healthcare system via Medicaid programs surely cannot result in lasting coverage. In-network physicians will continue to dwindle as their office overhead exceeds meager reimbursement levels.

In reality, treating Medicaid patients is charity work. The fact that any physicians accept Medicaid is a testament to their generosity of spirit and missionary mindset. Expanding their pro bono workloads is nothing to cheer about. The Affordable Care Act’s “signature accomplishment” is tragically flawed – because offering health insurance to people that physicians cannot afford to accept is not better than being uninsured.

After all, improved access to nothing… offers nothing. Inviting physicians to work for less than minimum wage so that politicians can crow about millions of uninsured Americans now having access to healthcare, is ridiculous. Medicaid expansion is widening the gap between the haves and the have-nots. The saddest part is that the have-nots just don’t realize it yet.

May 1st, 2014 by Dr. Val Jones in Health Tips, Opinion

1 Comment »

A well-to-do patient recently boasted to me about an expensive insurance plan that he had purchased to “guarantee” that he had access to the best healthcare in the United States. Coverage included access to elite academic centers (all the usual suspects) and a private jet service for emergencies. He was utterly confident that his investment was worth the price, but I withheld my own misgivings.

A well-to-do patient recently boasted to me about an expensive insurance plan that he had purchased to “guarantee” that he had access to the best healthcare in the United States. Coverage included access to elite academic centers (all the usual suspects) and a private jet service for emergencies. He was utterly confident that his investment was worth the price, but I withheld my own misgivings.

Hospital quality data suggest that “fancy, brand name hospitals” provide better patient care. But unfortunately there is no guarantee of good outcomes for anyone who sets foot in a hospital. My experience doesn’t exactly square with quality data, and although I realize that there are teams of public and private sector analysts out there furiously rating and ranking hospitals with all manner of outcomes data, I don’t think it means a whole lot for the individual “worried well” patient. Here’s why:

1. Higher overall patient complexity may mean less attention for you. Academic medical centers specialize in caring for those who are often too sick or too complicated to be cared for elsewhere. This means that each patient requires more staff time to address their long list of diseases and conditions. Everything from medication reconciliation to medical testing, to bedside care, requires more time from each provider taking care of them. If you happen to be on a medical floor with complicated neighbors, expect to see less of your doctors and nurses. It’s not fair, but this happens regularly at elite centers, and it’s not in your best interest.

2. Less-experienced physicians may be providing the bulk of your care. Academic teaching hospitals are actively involved in training young doctors, and the least experienced among them will likely be providing the majority of your care (and reporting up to the overseeing physicians). Because of the exhausting complexity of very sick patients, if you are not among the very sickest (or provide a steady stream of diagnostic conundrums requiring the input and expertise from the top experts), your care will be left in the hands of the residents. This doesn’t mean you won’t get good care, but it introduces some degree of risk.

3. You may be exposed to really bad germs. Drug-resistant bacteria are born in places that use big-gun antibiotics. Again, with more challenging cases and infectious diseases in the patient mix, more antibiotics are used and more drug-resistant bacteria develop. Although academic centers make great efforts not to spread infections, it can happen. And if you do get a hospital-acquired infection, it’s probably going to be a bad one.

4. More providers means more opportunity to make EMR-based medical errors. As I’ve argued in recent blog posts, electronic medical records are error prone for a number of reasons. The more people entering data into your record, the more opportunity for mix ups and confusions. Academic medical centers may boast more specialists and a higher staff to patient ratio, but this is not always a good thing. The fewer the number of providers caring for you (especially nurses), the better you are known to them, and therefore the lower the risk of certain mistakes.

5. More tests and procedures aren’t always a good thing. Academic centers have access to a larger breadth of technology, which means that they are more likely to order more tests and procedures. Imaging studies, biopsies, lab tests, and advanced surgical procedures can provide additional information that can change the course of therapy. But they also have the ability to initiate wild goose chases, further testing, unnecessary anxiety, and additional risk (and expense) to the patient. Judicious use of technology is important, but with less experienced physicians on the team, they are more likely to reflexively order a test than to rely on their clinical experience regarding diagnosis and treatment.

6. Many “moving parts” increase your risk for errors, mix ups, and longer wait times. The larger the hospital, the more chances there are for accidental substitutions, name confusion, and test scheduling conflicts. It may seem improbable that these events still occur (Don’t we have bar codes on wrist bands that have solved this problem? You ask.), but if you’re a physician clicking between electronic medical records of patients with the same last name, no bar code will save you. I myself was a patient in the ER of a large elite academic center once, when the security guards confused me with a volatile psychotic patient previously located in the bay that my stretcher was moved into. They almost got the four-point restraints on before I convinced them to re-check my identity with the nurses. Awkward. Also, if you need an MRI or CT scan at a level 1 trauma center, you could be waiting a long time for it as sicker patients bump you from the schedule.

7. Traveling to a center of excellence means post-acute care services will be harder to arrange. If you are recovering from a serious illness or surgery far away from home, case managers will probably have a harder time connecting with services to help you upon discharge. If you need visiting nurses, home-based therapists, durable medical equipment, or follow up care (either with specialists or primary care physicians) all of that will be more challenging to arrange because the case managers don’t have them in their virtual Rolodex. Because of the complexity of the healthcare system, it takes years of effort for good case managers and discharge planners to streamline the process of getting through to the “right person” at each service provider and providing them with the “correct” insurance information and completed forms and paperwork. If they’re lobbying for you out of state or in a far away county, they will probably end up spending a lot of time on hold, or talking to the wrong person. And when you finally arrive home and the visiting nurse doesn’t show up, or you don’t have your walker after all… you will not be happy.

8. You may be stuck with an enormous, post-hospital price tag. Most people nowadays have insurance that covers care at certain “preferred” facilities at a much lower cost to the patient. If you go “outside of network” you may be responsible for a much higher percentage of your care cost than you bargained for. Before you decide to opt for the big brand name academic medical center for your care or procedure, double check with your insurance provider regarding what your part of the cost will be.

If you (or your loved one) are in the unfortunate position of having a rare, life-threatening, or extremely complicated host of diseases and conditions, then you may have no choice but to go to an academic medical center for care. If you’re like my wealthy patient, though, and can afford what you think are insurance upgrades to provide you with access to the “best care available,” you may discover that better care is actually found closer to home.

In an upcoming post, I’ll describe my experience with hospital characteristics that tend to predict a higher quality of care. You may be surprised to find that there isn’t a whole lot of overlap between my personal measures and what we are led to believe are the important ones. 🙂

November 28th, 2012 by Dr. Val Jones in Health Policy, Opinion, Primary Care Wednesdays

No Comments »

Animal research has shown that the best way to get a rat to press a pellet-producing lever is to set the mechanism so that it doesn’t always release a pellet with each push. The unpredictability (or scarcity) of the reward causes the rat to seek it with more fervor. Casino owners are well aware of this phenomenon, gaming our brain’s natural wiring so that our occasional wins drive us to lose more than we would if our winning had a predictable pattern.

Animal research has shown that the best way to get a rat to press a pellet-producing lever is to set the mechanism so that it doesn’t always release a pellet with each push. The unpredictability (or scarcity) of the reward causes the rat to seek it with more fervor. Casino owners are well aware of this phenomenon, gaming our brain’s natural wiring so that our occasional wins drive us to lose more than we would if our winning had a predictable pattern.

I believe that the same principle is at work in physician reimbursement. Although most patients don’t realize this, physicians aren’t always paid for the work they do, and they are paid wildly different rates depending on how they code an encounter or procedure. After several health insurance denials of payment for legitimate work, physicians look for ways to offset their losses. Those may include changing the coding of their procedures to enhance the rate of reimbursement, exaggerating the complexity of an encounter, or (less commonly) billing for things they didn’t do. Because of the perceived injustice in a system that randomly denies payment for legitimate work, the physician feels less morally concerned about her over billing and coding foibles.

And so a vicious cycle of reimbursement deprivation, followed by fraud and abuse, becomes the norm in the U.S. healthcare system. Payers say that physicians are greedy and unethical, and physicians say that payers deny reimbursement unfairly and pay rates that are too low to be sustainable. The government’s response is to hire a cadre of auditors to ferret out physician fraud while cutting reimbursement to physicians further. This is similar to reducing the rate of pellet release to the rats in the Skinner boxes, while randomly electrocuting them through the metal flooring. The result will be that rats will work harder to find work-arounds to get their pellets, including gathering together into larger groups to share pellets. This is occurring more and more commonly as solo practitioners are joining hospitals or large group practices to make ends meet.

But we need to realize a few things about the “Skinner box healthcare system:”

1. Rats are not evil because they press levers manically when there is a scarcity of pellets. Physicians are not evil when they look for ways to make up lost revenue. While fraud and abuse are always wrong, it is not surprising that they are flourishing in an environment of decreasing reimbursement and increasing health insurance payment denials. If we want to address fraud and abuse, we need to understand why it’s happening so that our “solutions” (i.e. hiring thousands more government auditors to investigate medical practices) don’t end up being as useless as shocking the rats.

2. Health insurance (whether public or private) is not evil for trying to rein in costs. Payers are in the unenviable position of having to say “no” to certain expenditures, especially if they are of marginal benefit. With rats pressing levers at faster and faster rates for smaller and smaller pellets, all manner of cost containment mechanisms are being applied. Unfortunately they are instituted randomly and in covert manners (such as coding tricks and bureaucratic red tape) which makes the rats all the more manic. Not to mention that expensive technology is advancing at a dizzying rate, and direct-to-consumer advertising drives demand for the latest and greatest robot procedure or biotech drug. Costs are skyrocketing for a number of good and bad reasons.

3. There is a way out of the Skinner box for those primary care physicians brave enough to venture out. Insurance-free practices instantly remove one’s dietary reliance on pellets, therefore eliminating the whole lever pressing game. I joined such a practice several years ago. As I have argued many times before, buying health insurance for primary care needs is like buying car insurance for your windshield wipers. It’s overkill. Paying cash for your primary care allows you to save money on monthly insurance premiums (high deductible plans cost much less per month) and frees up your physician to care for you anywhere, anytime. There is no need to go to the doctor’s office just so that they can justify billing your insurance. Pay them for their time instead (whether by phone, in-person, or at your home/place of business) and you’ll be amazed at the convenience and efficiency derived from cutting out the middle men!

Conclusion: The solution to primary care woes is to think outside the box. Patient demand is the only limiting factor in the growth of the direct-pay market. Patients need to realize that they are not limited to seeing “only the physicians on their health insurance list” – there is another world out there where doctors make house calls, solve your problems on the phone, and can take care of you via Skype anywhere in the world. Patients have the power to set physicians free from their crazy pellet-oriented existence by paying cash for their health basics while purchasing a less expensive health insurance plan to cover catastrophic events. Saving primary care physicians from dependency on the insurance model is the surest path to quality, affordable healthcare for the majority of Americans. Will you join the movement?

November 21st, 2012 by Dr. Val Jones in Health Policy, Opinion

No Comments »

In a recent post entitled, “The Joys Of Health Insurance Bureaucracy” I described how it took me (a physician) over three months to get one common prescription filled through my new health insurance plan. Of note, I have still been unable to enroll in the prescription refill mail order service that saves my insurer money and (ostensibly) enhances my convenience. The prescription benefits manager (PBM) has lost three of my physician’s prescriptions sent to them by fax, and as a next step have emailed me instructions to complete an online form so that they have permission to contact my physician directly (to confirm the year’s refills). Unfortunately, page one of the form requires you to fill in your drug name and match it to their database’s list before you can continue to page two. For reasons I can’t understand, my common drug is not in their database. Therefore, I am unable to comply with my insurer’s wish that I enroll in mail order prescription refills. This will further delay receipt of my medication – and probably increase my cost as I will be penalized for not opting into the “preferred” mail order refill process.

In a recent post entitled, “The Joys Of Health Insurance Bureaucracy” I described how it took me (a physician) over three months to get one common prescription filled through my new health insurance plan. Of note, I have still been unable to enroll in the prescription refill mail order service that saves my insurer money and (ostensibly) enhances my convenience. The prescription benefits manager (PBM) has lost three of my physician’s prescriptions sent to them by fax, and as a next step have emailed me instructions to complete an online form so that they have permission to contact my physician directly (to confirm the year’s refills). Unfortunately, page one of the form requires you to fill in your drug name and match it to their database’s list before you can continue to page two. For reasons I can’t understand, my common drug is not in their database. Therefore, I am unable to comply with my insurer’s wish that I enroll in mail order prescription refills. This will further delay receipt of my medication – and probably increase my cost as I will be penalized for not opting into the “preferred” mail order refill process.

Now, all of this is infuriating enough on its own, but the larger concern that I have is this: How many patients are not “compliant” with their medication regimen because of problems/delays with their health insurer or PBM? Physicians are being held accountable for their patients’ medication compliance rates, even receiving lower compensation for patients who don’t reach certain goals. This is called “pay-for-performance” and it’s meant to incentivize physicians to be more aggressive with patient follow up so that people stay healthier. But all the follow up in the world isn’t going to get patient X to take their medicine each day if their health insurer or PBM makes it impossible for them to get it in the first place. And shouldn’t there be consequences for such excessive red tape? Who is holding the insurers and PBMs accountable for their inefficiencies that prevent patients from getting their medicines in a timely manner?

Pay-for-performance assumes that physicians are the only healthcare influencers in the patient compliance cycle. I’ve learned that we only play a part in helping people stay on the best path for their health. Other key players can derail our best intentions, and it’s high time that we look at the poor performance of health insurers and PBMs as they often block (with intentional bureaucracy) our patients from getting the medicine they need. While insurers save money by having patients struggle to get their prescriptions filled, doctors are payed less when patients don’t take their medicines.

Not a great time to be a doctor or a patient… or both.

Over 1 million virtual doctor visits were reported in 2015. Telehealth companies have long asserted that increased access to physicians via video or phone conferencing saves money by reducing office visits and Emergency Department care. But a new study calls this cost savings into question. Increased convenience can increase utilization, which may improve access, but not reduce costs.

Over 1 million virtual doctor visits were reported in 2015. Telehealth companies have long asserted that increased access to physicians via video or phone conferencing saves money by reducing office visits and Emergency Department care. But a new study calls this cost savings into question. Increased convenience can increase utilization, which may improve access, but not reduce costs.

A physician

A physician  A well-to-do patient recently boasted to me about an expensive insurance plan that he had purchased to “guarantee” that he had access to the best healthcare in the United States. Coverage included access to elite academic centers (all the usual suspects) and a private jet service for emergencies. He was utterly confident that his investment was worth the price, but I withheld my own misgivings.

A well-to-do patient recently boasted to me about an expensive insurance plan that he had purchased to “guarantee” that he had access to the best healthcare in the United States. Coverage included access to elite academic centers (all the usual suspects) and a private jet service for emergencies. He was utterly confident that his investment was worth the price, but I withheld my own misgivings.

In a recent post entitled, “

In a recent post entitled, “