November 9th, 2012 by Dr. Val Jones in Health Policy, Humor, Opinion

4 Comments »

If you live in a small town or rural area of the United States, you may have noticed that family doctors are becoming an endangered species. Private and public health insurance reimbursement rates are so low that survival as a solo practitioner (without the economies of scale of a large group practice or hospital system) is next to impossible. Some primary care physicians are staying afloat by refusing to accept insurance – this allows them the freedom to practice medicine that is in the patient’s best interest, rather than tied to reimbursement requirements.

If you live in a small town or rural area of the United States, you may have noticed that family doctors are becoming an endangered species. Private and public health insurance reimbursement rates are so low that survival as a solo practitioner (without the economies of scale of a large group practice or hospital system) is next to impossible. Some primary care physicians are staying afloat by refusing to accept insurance – this allows them the freedom to practice medicine that is in the patient’s best interest, rather than tied to reimbursement requirements.

I joined such a practice a few years ago. We make house calls, answer our own phones, solve at least a third of our patients’ problems via phone (we don’t have to make our patients come into the office so that we can bill their insurer for the work we do), and have low overhead because we don’t need to hire a coding and billing team to get our invoices paid. Our patients love the convenience of same day office visits, electronic prescription refills, and us coming to their house or place of business as needed.

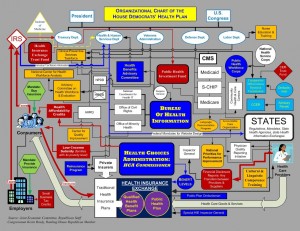

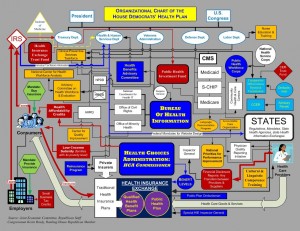

Using health insurance to pay for primary care is like buying car insurance for your windshield wipers. The bureaucracy involved raises costs to a ridiculously unreasonable level. I wish that more Americans would decide to pay cash for primary care and buy a high deductible health plan to cover catastrophic events. But until they do, economic pressures will force primary care physicians into hospital systems and large group practices. My friend and fellow blogger Dr. Doug Farrago likens this process to being “assimilated by the Borg.”

Doug offered a challenge to his readers – to customize the definition of Star Trek’s Borg species to today’s healthcare players. I gave it my best shot. Do you have a better version?

Who are the Borg:

The Borg are a collection of alien species that have turned into cybernetic organisms functioning as drones of the collective or the hive. A pseudo-race, dwelling in the Star Trek universe, the Borg take other species by force into the collective and connect them to “the hive mind”; the act is called assimilation and entails violence, abductions, and injections of cybernetic implants. The Borg’s ultimate goal is “achieving perfection”.

My attempt to customize the definition:

Hospitalists are a collection of primary care physicians that have turned into cybernetic organisms functioning as drones of the collective or hive. Hive collective administrators (HCAs), in association with partnered alien species drawn from the insurance industry and government, take other primary care physicians by economic force and connect them to “the hive mind”; the act is called assimilation and entails crippling reimbursement cuts, massive increases in documentation requirements, oppressive professional liability insurance rates, punitive bureaucratic legislation, and threat of imprisonment for failure to adhere to laws that HCA- partnered species interpret however they wish. The HCAs’ ultimate goal is “achieving perfect dependency” first for the drones, then for their patients, so that HCAs and their alien partners will become all powerful – dictating how neighboring species live, breathe, and conduct their affairs. Resistance is futile.

***

To learn more about my insurance-free medical practice, please click here. We can unplug you from the Borg ship!

October 15th, 2012 by Dr. Val Jones in Health Policy, Health Tips, True Stories

5 Comments »

From a health perspective, I am grateful to be doing well. I have only one active medical condition that is fully treated by one prescription medicine. I have been taking this medicine since I was 18 years old. I recently bought myself a personal health insurance plan (my first that was not tied to employment) and simply wanted to resume regular purchase and use of my medicine.

From a health perspective, I am grateful to be doing well. I have only one active medical condition that is fully treated by one prescription medicine. I have been taking this medicine since I was 18 years old. I recently bought myself a personal health insurance plan (my first that was not tied to employment) and simply wanted to resume regular purchase and use of my medicine.

I was pleased to note that purchasing my medicine through the new insurance plan would save me a little bit of money (about $25/month). So I presented my card at the local pharmacy and was told that my medicine was not covered under my plan without pre-authorization from my doctor. I called my pharmacy benefits hotline and had them send a pre-auth form to my doctor. Then I asked him to fill out the form and fax it back. That was over three months ago.

When I called to inquire about the pre-auth forms, the benefits folks told me that they had no record of the fax. So I asked my doctor to send another fax form and I waited another week. When I called the benefits people, they again said that they had no record of the pre-auth documentation. They also said that I could not be transferred to the pre-auth team to figure out why it was missing (wrong fax number perhaps?) because they only speak to providers.

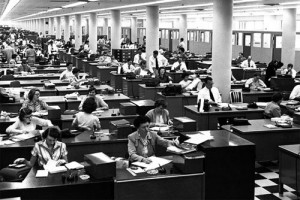

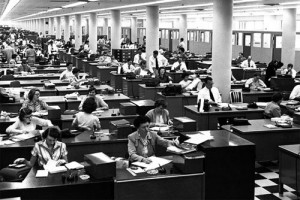

So out of curiosity I asked what the usual process was for obtaining a prescription medication once it has been authorized. The benefits staff didn’t know. I asked who would know and they said that only the “experts” in the pre-auth department know how medications are obtained by the member after being approved. I wondered how I’d ever figure this out if I wasn’t allowed to speak to them and I was told that I might be able to get an answer if I asked a customer care representative to request information on my behalf from the pre-auth experts. But… the pre-auth team was not in the office at the moment and I’d need to call back on Monday. (Parenthetically, the team is physically located in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, though I’m a member in Charleston, South Carolina.)

I asked the benefits team if they generally mail members their meds (I had heard this was the case) or if I could pick them up at my local pharmacy (my preference). They said they didn’t know, but I could call customer care on Monday.

So far, my experience with my new plan – to save $25 dollars/month on one prescription – has cost me 3 months and 1 week of waiting time, two form completion episodes with my doctor, discussions with several pharmacy benefits reps in a state far away from where I live, denial of communication with the only people who know what’s potentially holding up my prescription approval, and about a half hour of completely unhelpful discussion of basic prescription drug purchasing processes that staff at the drug benefits company themselves don’t understand.

And I’m healthy, I’m a healthcare provider who knows how to navigate the system, and I only need one prescription. What do sick people do? (I know, it’s awful out there.)

Life was much simpler when I paid for my medication out-of-pocket without an insurance middle man. I have often wondered if health insurance bureaucracy is purposefully designed to wear patients down to the point where they’ll just pay for things themselves rather than experience the pain associated with getting an insurance company to cover their portion of the cost. (The only other explanation is that health insurance company ineptitude comes from being administrative behemoths with too many moving parts and processes). It’s probably a mix of the two. Or maybe the latter supports the former so there’s no real incentive to pursue true efficiency.

But one thing I did notice – the insurance company was incredibly efficient at figuring out how to direct debit my premiums within 24 hours of signing up for the plan, and have increased my premium once already – by about $25 a month.

You can’t win, my friends.

If you’re healthy, get yourself a high deductible plan, pay as little in premiums as possible, and sock away some money in case of a catastrophic event. Pay cash for your primary care, and do whatever you can to stay healthy and out of the hospital. That’s my plan and I’m sticking to it.

***

Update: My medicine was finally approved/authorized, but I was informed that my doctor would need to send a new Rx form to them before I could receive my prescription. The Rx needed to be on their company’s form, so they had to fax him the request first. I asked how I would pay for the prescription and where I could pick it up and was informed that I’d save about 15% if I agreed to have the medicine mailed to my home (but delivery would take 2 extra weeks).

So I agreed to have it mailed to my home and offered to give them my credit card. They said I should call back with it once my doctor’s Rx had been received. I asked them how I would know when that had occurred. They said that they couldn’t call me to tell me when the Rx had arrived because I had selected “text messaging” as my preferred method of contact, and they don’t inform members of Rx form receipt via text messaging. So I agreed to switch my preference to calls (instead of text), and now I’ll probably get automated prescription refill information in the form of incoming calls on my personal work phone from now till I die. That’s if they don’t sell my phone number to telemarketers in the mean time.

And how annoying is it for my doctor to have sent out two faxes and one new Rx form for ONE prescription (not to mention reading the email explanations from me regarding correct pharmacy benefits plan form usage)? He was uncompensated for his time in this matter…

August 20th, 2012 by Dr. Val Jones in Health Policy, Opinion

No Comments »

Health Leaders Media recently published an article about “the latest idea in healthcare: the informed shared medical decision.” While this “latest idea” is actually as old as the Hippocratic Oath, the notion that we need to create an extra layer of bureaucracy to enforce it is even more ridiculous. The author argues that physicians and surgeons are recommending too many procedures for their patients, without offering them full disclosure about their non-procedural options. This trend can be easily solved, she says, by blocking patient access to surgical consultants:

Health Leaders Media recently published an article about “the latest idea in healthcare: the informed shared medical decision.” While this “latest idea” is actually as old as the Hippocratic Oath, the notion that we need to create an extra layer of bureaucracy to enforce it is even more ridiculous. The author argues that physicians and surgeons are recommending too many procedures for their patients, without offering them full disclosure about their non-procedural options. This trend can be easily solved, she says, by blocking patient access to surgical consultants:

“The surgeon isn’t part of the process. Instead, patients would learn from experts—perhaps hired by the health system or the payers—whether they meet indications for the procedure or whether there are feasible alternatives.”

So surgeons familiar with the nuances of an individual’s case, and who perform the procedure themselves, are not to be consulted during the risk/benefit analysis phase of a “shared” decision. Instead, the “real experts” – people hired by insurance companies or the government – should provide information to the patient.

I understand that surgeons and interventionalists have potential financial incentives to perform procedures, but in my experience the fear of complications, poor outcomes, or patient harm is enough to prevent most doctors from performing unnecessary invasive therapies. Not to mention that many of us actually want to do the right thing, and have more than enough patients who clearly qualify for procedures than to try to pressure those who don’t need them into having them done.

And if you think that “experts hired by a health insurance company or government agency” will be more objective in their recommendations, then you’re seriously out of touch. Incentives to block and deny treatments for enhanced profit margins – or to curtail government spending – are stronger than a surgeons’ need to line her pockets. When you take the human element out of shared decision-making, then you lose accountability – people become numbers, and procedures are a cost center. Patients should have the right to look their provider in the eye and receive an explanation as to what their options are, and the risks and benefits of each choice.

I believe in a ground up, not a top down, approach to reducing unnecessary testing and treatment. Physicians and their professional organizations should be actively involved in promoting evidence-based practices that benefit patients and engage them in informed decision making. Such organizations already exist, and I’d like to see their role expand.

The last thing we need is another bureaucratic layer inserted in the physician-patient relationship. Let’s hold each other accountable for doing the right thing, and let the insurance company and government “experts” take on more meaningful jobs in clinical care giving.

July 27th, 2012 by Dr. Val Jones in Health Policy, Opinion

5 Comments »

New York Times blogger Tara Parker Pope describes how her daughter was recently “the victim” of excessive medical investigation. Apparently, the little girl twisted her ankle at dance camp and experienced a slower than normal recovery. Four weeks out from the sprain, Tara sought the help of a specialist rather than returning to her pediatrician. The resulting MRI led to blood testing, which led to more testing, and more specialist input, etc. until the costs had spiraled out of control – not that Tara cared much because (as she admits) “I had lost track because it was all covered by insurance.”

New York Times blogger Tara Parker Pope describes how her daughter was recently “the victim” of excessive medical investigation. Apparently, the little girl twisted her ankle at dance camp and experienced a slower than normal recovery. Four weeks out from the sprain, Tara sought the help of a specialist rather than returning to her pediatrician. The resulting MRI led to blood testing, which led to more testing, and more specialist input, etc. until the costs had spiraled out of control – not that Tara cared much because (as she admits) “I had lost track because it was all covered by insurance.”

Instead of any twinge of guilt on the part of Ms. Pope for having single-handedly called in the cavalry for an ankle sprain, she concluded that her daughter was a victim of medical over-investigation. But what would any physician do in the face of a concerned pseudo-celebrity parent (with a huge platform from which to complain about her medical treatment)? The doctor would leave no stone unturned, so as to protect herself from accusations of “missing a diagnosis” or being insufficiently concerned about the ankle sprain.

The responses to Ms. Pope’s personal “horror story” about over-treatment (and the waste of billions of dollars inherent in the US medical system) were amusing. One commenter writes, “Why not think of the unnecessary $210 billion as a fiscal ‘stimulus?’ Makes as much sense as any other program in the Age of Obama/Krugman.” And another, “[Of course there’s over-treatment] because the federal government subsidizes it! Medicaid, Medicare, and third party private insurance all promote the use of wasteful health care spending. And Obamacare will put that process on steroids.”

Whether or not you agree that socialized medicine reduces healthcare costs, it seems to me that we all have a responsibility not to over-utilize medical resources so that they will still be there when we really need them. Over-investigating every pediatric ankle sprain will simply drain our collective resources, ultimately resulting in further healthcare rationing. New York Times writer Peter Singer has argued that rationing is inevitable and decisions about cancer drug treatment will become the purview of US government agencies as time goes on. I’m pretty sure he’s right.

That being the case, why spur on rationing? Ms. Pope’s victim mentality demonstrates her lack of insight into the true causes of rising healthcare costs – one of which is patient demand. Ms. Pope herself is contributing to the healthcare waste she despises by requesting excessive testing in an environment where physicians are afraid to say no due to legal pressures (or a NYT writer’s bully pulpit). Demand drives costs, and there is a finite limit on our resources. Personal responsibility must play a role in healthcare utilization, just as efforts to protect our environment and scarce resources require participation by individuals. Ultimately, one child’s ankle investigation comes at the price of another patient’s cancer treatment.

Was it the physicians’ responsibility to put the brakes on her daughter’s over-testing? Maybe, but I’d prefer to live in a world where patients can invoke additional testing when their personal judgment suggests that it’s important. Ms. Pope knew better, but requested the additional testing because her insurance paid for it. Free care leads to more care – especially more unnecessary care. Ms. Pope’s daughter was not a victim of over-testing, but a beneficiary of that luxury that may soon evaporate.

We can create a healthcare system where no ankle gets more than a physical exam and ibuprofen (so we can forcibly prevent over-utilization), or we can teach people to use healthcare resources responsibly. Unfortunately, that will require that patients have a little more financial skin in the game – as Ms. Pope has demonstrated. The alternative, a distant oversight body regulating what you can and can’t have access to in healthcare, is where we’ll probably end up. Some day in the future Ms. Pope will recall the day when she was able to get unlimited medical investigations for her daughter without question or cost, and she’ll marvel at how that freedom has been lost. By that time, I suppose, I’ll be one of those people who is being denied cancer treatment by my government.

June 20th, 2012 by Dr. Val Jones in Health Policy, Health Tips, News, Opinion

No Comments »

The American Medical Association (AMA) voted today to endorse taxation of sugary beverages as a means to raise money for anti-obesity programs. Interestingly, a recent physician survey at Medpage Today suggests that only 50% of physicians think that a soda tax is an effective public health strategy.

I am one of the 50% who feels that this policy will not be effective. In short, this is why:

1. You can become obese by eating and drinking almost anything in excess. Targeting sugary beverages is reductio ad absurdum. Did America become fat simply because of an excess supply of sugary fluids on grocery shelves? What about the super-sizing of our food portions, the change in workforce physical requirements, the advent of cars, escalators, healthy food “deserts” in poor neighborhoods, video games, and cutting gym class from schools?

Holding Coca Cola, et al. responsible for our own over-consumption of calories is both unfair and tantamount to spitting into the wind – something bad is going to come back at us. Consumers can easily get around the soda tax by buying sweet alternatives – which may have even more calories than soda. (Caramel latte anyone?) And then what? Are we really going to play public policy, food and beverage whack-a-mole?

Carmelita Jeter's Shopping Cart

2. You can be thin and fit while eating and drinking almost anything. Obviously nutrition science has shown that a diet rich in fresh fruits and veggies, lean meats, low-fat dairy, whole grains, and healthy fats is the best for our health. However, please consider that the world’s fastest woman, Olympian Carmelita Jeter, eats Hostess cup cakes, Teddy Grahams, Welch’s grape juice, whole milk, and Gatorade. How do I know? Because she posted a photo of her shopping cart on Twitter (see image to the left). I obviously have no idea how much of this she eats – or when she eats it – but if the world’s fastest woman is powered (to some degree) by “Twinkies” then I think we should all think twice about demonizing certain foods/beverages in our anti-obesity fervor.

3. You can’t regulate good behavior. Human behaviors that may lead to obesity are simply too complex to regulate. Who would want to live in a world where government becomes the de facto “Nutrisystem” for its citizens, mailing out pre-packaged, ingredient-controlled meals to 312 million people per day, three times a day, seven days a week? While that may save the post office from its imminent demise, we can neither afford to do that, nor do we need to.

People who believe that policy should drive behavior point to smoking bans that have cut down on smoking rates. While I agree that small improvements have been made in reducing smoking rates, roughly one in four people still smoke (depending on your source, this number could be as low as one-in-five), and one in every five deaths is still attributed to cigarette smoking. Hardly a resounding victory, alas.

But beyond the fact that policy changes (and the billions we’ve spent enacting and enforcing them) have resulted in a disappointing decrease in smoking rates, is the issue that cigarettes and food ingredients (such as sugar) are not analogous substances. While there is no safe minimum amount of cigarette smoke, our bodies need salt, glucose, and fat to survive. They cannot be cut out of our diet completely – nor should they. And the only way to force people to optimize their intake is to enact Draconian measures.

So instead of starting a food-fight, it’s important to accept the complexities associated with this particular health scourge and promote a broader, more-nuanced approach to wellness incentives. We have to attack this problem from the ground up, because a top-down approach requires our government to become an invasive, food and exercise nanny.

The good news is that one-third of Americans are not overweight or obese, despite our current “toxic” food/inactive lifestyle environment. Perhaps these thinner folks can be ambassadors for the rest of us, and reveal their secrets of healthy living despite our current limitations. Even with our best efforts, we need to understand that (like smokers) we will always have a segment of the population that is overweight or obese.

And as for the Olympians among us – they help to illustrate that obsessing over every morsel of food or cup of soda that we consume is not the way forward. Sorry AMA, I’m with Carmelita on this one.

Powered By Twinkies?

If you live in a small town or rural area of the United States, you may have noticed that family doctors are becoming an endangered species. Private and public health insurance reimbursement rates are so low that survival as a solo practitioner (without the economies of scale of a large group practice or hospital system) is next to impossible. Some primary care physicians are staying afloat by refusing to accept insurance – this allows them the freedom to practice medicine that is in the patient’s best interest, rather than tied to reimbursement requirements.

If you live in a small town or rural area of the United States, you may have noticed that family doctors are becoming an endangered species. Private and public health insurance reimbursement rates are so low that survival as a solo practitioner (without the economies of scale of a large group practice or hospital system) is next to impossible. Some primary care physicians are staying afloat by refusing to accept insurance – this allows them the freedom to practice medicine that is in the patient’s best interest, rather than tied to reimbursement requirements.

Health Leaders Media recently

Health Leaders Media recently New York Times blogger Tara Parker Pope

New York Times blogger Tara Parker Pope