September 7th, 2012 by Dr. Val Jones in Health Tips, Opinion

Tags: BMI, Coaching, Counseling, Education, Information, Motivation, NPR, Obesity, Physician's BMI, Podcast, Ranit Mishori, USPSTF recommendations, Weight Loss

No Comments »

I recently found my way to an interesting NPR podcast via a link from Dr. Ranit Mishori (@ranitmd) on Twitter. The host of the show interviewed a physician (Dr. Mishori), an obesity researcher (Sara Bleich), and a family nurse practitioner (Eileen O’Grady) about how healthcare providers are trying (or not trying) to help patients manage their weight. Several patients and practitioners called in to participate.

I recently found my way to an interesting NPR podcast via a link from Dr. Ranit Mishori (@ranitmd) on Twitter. The host of the show interviewed a physician (Dr. Mishori), an obesity researcher (Sara Bleich), and a family nurse practitioner (Eileen O’Grady) about how healthcare providers are trying (or not trying) to help patients manage their weight. Several patients and practitioners called in to participate.

First of all, I found it intriguing that research has shown that the BMI of the treating physician has a significant impact on whether he or she is willing to counsel a patient about weight loss. Normal weight physicians (those with a BMI under 25) were more likely to bring up the subject (and follow through with weight loss and exercise planning with their patients) than were physicians who were overweight or obese. Sara Bleich believes that this is because overweight and obese physicians either don’t recognize the problem in others who have similar body types, or that their personal shame about their weight makes them feel that they don’t have the right to give advice since they don’t practice what they preach. While 60% of Americans are either overweight or obese, 50% of physicians are also in those categories.

Although it’s not entirely surprising that overweight/obese physicians feel as they do, it made me wonder what other personal conditions could be influencing evidence-based patient care. Is a physician with high blood pressure less apt to encourage salt restriction or medication adherence? What about depression, smoking cessation, or erectile dysfunction? Are there certain personal diseases or conditions that impair proper care and treatment in others?

Several callers recounted negative experiences with physicians where they were “read the Riot Act” about their weight. One overweight woman said she handled this by simply avoiding going to the doctor at all, and another obese man said his doctor made him cry. However, the man went on to lose 175 pounds through diet and exercise modifications and said that the “tough love” was just what he needed to galvanize him into action.

Dr. Mishori felt that the “Riot Act” approach was rarely helpful and usually alienated patients. She advocated a more nuanced and sensitive approach that takes into account a patient’s social and financial situation. She explained that there’s no use advocating personal training sessions to a person on food stamps. Physicians need to be more sensitive to patients’ living conditions and physical abilities.

In the end, I felt that nurse practitioner Eileen O’Grady contributed some helpful observations – she argued that the rate-limiting factor in reversing obesity is not information, but motivation. Most patients know what they “should do” but just don’t have the motivation to start, and keep at it till they achieve a healthy weight. Ms. O’Grady devoted her practice to weight loss coaching by phone, and she believes that telephones have one big advantage over in-person visits: patients are more likely to be honest when there is no direct eye contact with their provider. Her secret to success, beyond a non-judgmental therapeutic environment, is setting small, attainable goals. She says that if she doesn’t believe the patient has at least a 70% chance of success, they should not set that particular goal.

Starting goals may be as simple as “finding a workout outfit that fits.” As the patient grows in confidence with their successes, larger, broader goals may be set. Weight loss coaching and intensive group therapy may be the most motivating strategy that we have to help Americans shed unwanted pounds. Apparently, the USPS Task Force agrees, as they recommend “intensive, multicomponent behavioral interventions” for those who screen positive for obesity in their doctors’ offices.

I think it’s unfortunate that most doctors feel that they “simply don’t have time to counsel patients about obesity.” Diet and exercise are the two most powerful medical tools we have to combat many chronic diseases. What else is so important that it’s taking away our time focusing on the “elephant in the room?” Pills are not the way forward in obesity treatment – and we should have the courage to admit it and do better with confronting this problem head-on in our offices, and also in our own lives.

August 20th, 2012 by Dr. Val Jones in Health Policy, Opinion

Tags: bureaucracy, CMS, Health Insurance, Informed Consent, medicaid, Medicare, Patient Rights, Physician-patient relationship, Procedures, Shared Decision-Making, Unnecessary Procedures

No Comments »

Health Leaders Media recently published an article about “the latest idea in healthcare: the informed shared medical decision.” While this “latest idea” is actually as old as the Hippocratic Oath, the notion that we need to create an extra layer of bureaucracy to enforce it is even more ridiculous. The author argues that physicians and surgeons are recommending too many procedures for their patients, without offering them full disclosure about their non-procedural options. This trend can be easily solved, she says, by blocking patient access to surgical consultants:

Health Leaders Media recently published an article about “the latest idea in healthcare: the informed shared medical decision.” While this “latest idea” is actually as old as the Hippocratic Oath, the notion that we need to create an extra layer of bureaucracy to enforce it is even more ridiculous. The author argues that physicians and surgeons are recommending too many procedures for their patients, without offering them full disclosure about their non-procedural options. This trend can be easily solved, she says, by blocking patient access to surgical consultants:

“The surgeon isn’t part of the process. Instead, patients would learn from experts—perhaps hired by the health system or the payers—whether they meet indications for the procedure or whether there are feasible alternatives.”

So surgeons familiar with the nuances of an individual’s case, and who perform the procedure themselves, are not to be consulted during the risk/benefit analysis phase of a “shared” decision. Instead, the “real experts” – people hired by insurance companies or the government – should provide information to the patient.

I understand that surgeons and interventionalists have potential financial incentives to perform procedures, but in my experience the fear of complications, poor outcomes, or patient harm is enough to prevent most doctors from performing unnecessary invasive therapies. Not to mention that many of us actually want to do the right thing, and have more than enough patients who clearly qualify for procedures than to try to pressure those who don’t need them into having them done.

And if you think that “experts hired by a health insurance company or government agency” will be more objective in their recommendations, then you’re seriously out of touch. Incentives to block and deny treatments for enhanced profit margins – or to curtail government spending – are stronger than a surgeons’ need to line her pockets. When you take the human element out of shared decision-making, then you lose accountability – people become numbers, and procedures are a cost center. Patients should have the right to look their provider in the eye and receive an explanation as to what their options are, and the risks and benefits of each choice.

I believe in a ground up, not a top down, approach to reducing unnecessary testing and treatment. Physicians and their professional organizations should be actively involved in promoting evidence-based practices that benefit patients and engage them in informed decision making. Such organizations already exist, and I’d like to see their role expand.

The last thing we need is another bureaucratic layer inserted in the physician-patient relationship. Let’s hold each other accountable for doing the right thing, and let the insurance company and government “experts” take on more meaningful jobs in clinical care giving.

August 15th, 2012 by Dr. Val Jones in Health Policy, Opinion

Tags: Atul Gawande, Cheesecake Factory, Healthcare Quality, Medical Errors, New Yorker, Process Improvement

1 Comment »

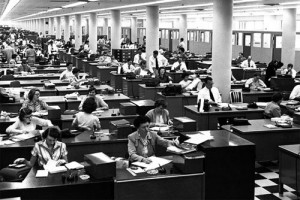

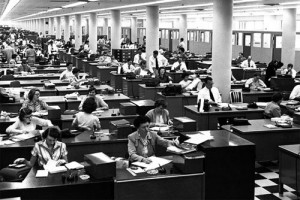

Hospitals can be dangerous and inefficient; therefore it is easy to connect with Atul Gawande’s recent New Yorker essay “BigMed” suggesting that the streamlined, production processes found at the Cheesecake Factory can and likely will be applied to healthcare. Yet hospital care should not be confused with the full spectrum of healthcare. One must make the distinction between the cognitive process of medical diagnosis occurring in exam rooms, with the procedural basis of surgical care and hospital recovery. While Dr. Gawande has provided a wonderful revealing portrait of cost-effective, fast, food preparation and delivery at the Cheesecake Factory, he has focused on the process of creating the meal, not the process of deciding what meal to make. Successful surgery, for the wrong diagnosis, is a problem. If we are to solve some of healthcare’s largest failings we should focus on what happens as physicians try to address their patient’s problems, diagnose and make decisions, at the table of medicine called the exam room.

Hospitals can be dangerous and inefficient; therefore it is easy to connect with Atul Gawande’s recent New Yorker essay “BigMed” suggesting that the streamlined, production processes found at the Cheesecake Factory can and likely will be applied to healthcare. Yet hospital care should not be confused with the full spectrum of healthcare. One must make the distinction between the cognitive process of medical diagnosis occurring in exam rooms, with the procedural basis of surgical care and hospital recovery. While Dr. Gawande has provided a wonderful revealing portrait of cost-effective, fast, food preparation and delivery at the Cheesecake Factory, he has focused on the process of creating the meal, not the process of deciding what meal to make. Successful surgery, for the wrong diagnosis, is a problem. If we are to solve some of healthcare’s largest failings we should focus on what happens as physicians try to address their patient’s problems, diagnose and make decisions, at the table of medicine called the exam room.

Consider the continuum of the patient encounter, from first symptoms, through diagnosis and therapy at a restaurant called Med. At Med I spend all of my shifts with my patrons at my tables. This is an unusual restaurant since the patrons are never sure of what they want to eat and appear every 20 minutes with ever changing lists of unique groups of ingredients to share with me. There are varying ingredients and thousands of meals that can be created. The patrons know the ingredients, but not the meal that they would like to eat. From memory I respond to the customers list of ingredients and ask many questions, take the pulse and other vital signs of the customer, order blood samples, radiographic studies and then decide for the patron which meal their ingredients add up to. All from memory. At Med, restaurant patrons also ask for foods and “food tests” they have seen on television all purported to be risk free. Further complicating the process is my customer is not out for a fun and relaxing evening, they are in small booths in skimpy, open at the back gowns, often anxious and uncertain if they will be harmed or poisoned by my foods, or simply receive a meal they do not want. Some are in pain and some are depressed, while other customers are totally unrealistic about the meal that is to be delivered. You see at Restaurant Med, where patrons only can speak to their wait staff about ingredients, and demand the modern but unhelpful ovens they heard about from friends and the media, it is really difficult to create meals that patrons thoroughly enjoy.

An appendectomy should be consistently performed and priced, but how do we consistently perform and price considering the ambiguity inherent in diagnosis itself? Unlike a restaurant, where customers choose a meal by ordering a meal, at restaurant Med some higher force gives an unfortunate person an undifferentiated and undiagnosed problem that needs and deserves an answer. As it turns out, none of the patrons really want to be eating at restaurant Med, as they always receive a meal they did not ask for.

Patients do not choose their diagnoses from menus; doctors must discover and diagnose them.

If your waiter tries to memorize all the orders at all the tables, you might get the wrong meal, and if your server is in a hurry, thai dipping sauce might be spilled on your new silk blouse. Likewise if physicians are in a rush, they might not take a thorough history, perform a complete physical exam, or have an accurate and thorough list of diagnostic possibilities, ultimately resulting in the wrong diagnosis. If your physician believes he or she can memorize all the questions, tied to all the possible diagnoses you also might receive the wrong diagnosis. With that wrong diagnosis you might end up in a hospital more efficient than the Cheesecake Factory with doctors efficiently ordering unnecessary tests, and performing wrong surgeries for the wrong diagnosis all with the ease and speed of the best assembly line on the planet.

Diagnostic and patient management error caused by cognitive mistakes in the exam room are all too often overlooked and unmentioned in the discussion of repairing our broken healthcare system. There are over a billion outpatient visits in the US each year, and numerous studies have shown 15-20% of these visits have an inaccurate diagnosis. Autopsy data proves this, malpractice insurers know this, and policy makers avoid it. Add diagnostic error in the emergency room and walk-in clinics to error in the out-patient offices of medicine and you have more than 200 million errors. If we are to resolve some of healthcare’s deepest woes we need to address diagnostic errors and the decision-making occurring at the restaurant table of medicine, the exam room. A bright light needs to be shined on the simple fact that there is too much to know, to ask and to apply during a 15 minute encounter unless the patient has the simplest of medical questions or problems. Medical informaticists, researchers and innovative companies are focusing on this essential limitation of medical decision-making by designing information systems to be used by physicians at the point of care, during the patient encounter. Problem oriented systems can also be designed for use by patients in advance of the visit, and the future holds home-based information coordinated with professional clinical decision support. These new information tools are beginning to take the guessing out of which ingredients (symptoms) relate to the meals that the patient ultimately receives (diagnosis and treatment). If medical care is truly to be driven back to primary care we need to arm the waiters of medicine with purposefully designed tools and training to resolve ambiguity, aid diagnosis and inform therapy in the exam room.

Art Papier MD

Art Papier MD is CEO of Logical Images the developer of www.visualdx.com a clinical decision support system, Associate Professor of Dermatology and Medical Informatics at the University of Rochester College of Medicine, and a Director of the Society To Improve Diagnosis In Medicine (SIDM) http://www.improvediagnosis.org/

July 27th, 2012 by Dr. Val Jones in Health Policy, Opinion

Tags: Ankle Sprain, Cancer Drugs, Health Insurance, Healthcare Waste, NHS, NICE, NYT, Rationing, Resources, Tara Parker-Pope, Well Blog

5 Comments »

New York Times blogger Tara Parker Pope describes how her daughter was recently “the victim” of excessive medical investigation. Apparently, the little girl twisted her ankle at dance camp and experienced a slower than normal recovery. Four weeks out from the sprain, Tara sought the help of a specialist rather than returning to her pediatrician. The resulting MRI led to blood testing, which led to more testing, and more specialist input, etc. until the costs had spiraled out of control – not that Tara cared much because (as she admits) “I had lost track because it was all covered by insurance.”

New York Times blogger Tara Parker Pope describes how her daughter was recently “the victim” of excessive medical investigation. Apparently, the little girl twisted her ankle at dance camp and experienced a slower than normal recovery. Four weeks out from the sprain, Tara sought the help of a specialist rather than returning to her pediatrician. The resulting MRI led to blood testing, which led to more testing, and more specialist input, etc. until the costs had spiraled out of control – not that Tara cared much because (as she admits) “I had lost track because it was all covered by insurance.”

Instead of any twinge of guilt on the part of Ms. Pope for having single-handedly called in the cavalry for an ankle sprain, she concluded that her daughter was a victim of medical over-investigation. But what would any physician do in the face of a concerned pseudo-celebrity parent (with a huge platform from which to complain about her medical treatment)? The doctor would leave no stone unturned, so as to protect herself from accusations of “missing a diagnosis” or being insufficiently concerned about the ankle sprain.

The responses to Ms. Pope’s personal “horror story” about over-treatment (and the waste of billions of dollars inherent in the US medical system) were amusing. One commenter writes, “Why not think of the unnecessary $210 billion as a fiscal ‘stimulus?’ Makes as much sense as any other program in the Age of Obama/Krugman.” And another, “[Of course there’s over-treatment] because the federal government subsidizes it! Medicaid, Medicare, and third party private insurance all promote the use of wasteful health care spending. And Obamacare will put that process on steroids.”

Whether or not you agree that socialized medicine reduces healthcare costs, it seems to me that we all have a responsibility not to over-utilize medical resources so that they will still be there when we really need them. Over-investigating every pediatric ankle sprain will simply drain our collective resources, ultimately resulting in further healthcare rationing. New York Times writer Peter Singer has argued that rationing is inevitable and decisions about cancer drug treatment will become the purview of US government agencies as time goes on. I’m pretty sure he’s right.

That being the case, why spur on rationing? Ms. Pope’s victim mentality demonstrates her lack of insight into the true causes of rising healthcare costs – one of which is patient demand. Ms. Pope herself is contributing to the healthcare waste she despises by requesting excessive testing in an environment where physicians are afraid to say no due to legal pressures (or a NYT writer’s bully pulpit). Demand drives costs, and there is a finite limit on our resources. Personal responsibility must play a role in healthcare utilization, just as efforts to protect our environment and scarce resources require participation by individuals. Ultimately, one child’s ankle investigation comes at the price of another patient’s cancer treatment.

Was it the physicians’ responsibility to put the brakes on her daughter’s over-testing? Maybe, but I’d prefer to live in a world where patients can invoke additional testing when their personal judgment suggests that it’s important. Ms. Pope knew better, but requested the additional testing because her insurance paid for it. Free care leads to more care – especially more unnecessary care. Ms. Pope’s daughter was not a victim of over-testing, but a beneficiary of that luxury that may soon evaporate.

We can create a healthcare system where no ankle gets more than a physical exam and ibuprofen (so we can forcibly prevent over-utilization), or we can teach people to use healthcare resources responsibly. Unfortunately, that will require that patients have a little more financial skin in the game – as Ms. Pope has demonstrated. The alternative, a distant oversight body regulating what you can and can’t have access to in healthcare, is where we’ll probably end up. Some day in the future Ms. Pope will recall the day when she was able to get unlimited medical investigations for her daughter without question or cost, and she’ll marvel at how that freedom has been lost. By that time, I suppose, I’ll be one of those people who is being denied cancer treatment by my government.

July 26th, 2012 by Dr. Val Jones in Health Tips, Opinion, True Stories

Tags: Athletes, Body fat, CDC, Chubby Trainers, Exercise Guidelines, Fitness, Fitness Coach, NWCR, Personal Trainers, Planet Fitness, Weight Loss, What Is Fit

6 Comments »

I was taken aback by a recent conversation I had with a gym owner. She is interested in encouraging middle-aged women to come to the gym for beginner-level fitness classes and was planning a strategy meeting for her staff and key clients. I asked if I could join and she said that I was expressly un-invited. Slightly miffed I asked why that was so – after all, I’m a rehab physician who has devoted my career to getting people moving.

I was taken aback by a recent conversation I had with a gym owner. She is interested in encouraging middle-aged women to come to the gym for beginner-level fitness classes and was planning a strategy meeting for her staff and key clients. I asked if I could join and she said that I was expressly un-invited. Slightly miffed I asked why that was so – after all, I’m a rehab physician who has devoted my career to getting people moving.

“You’re too advanced.” She said. “Beginners wouldn’t relate to the way you work out, we’re really more focused on creating a less intimidating environment for women.”

“You mean, like the Planet Fitness ads? The ones where athletes are not welcome?” I asked, confusedly.

“I don’t like those ads but the idea is the same. Beginners feel deflated by working out with people who are in far better shape. They don’t even want their instructor to look too fit.”

“You’re kidding me. Women would actually prefer working out with a chubby trainer?”

“Yes. In fact, I’ve had some women come to the gym and actually request NOT to be paired up with some of our personal trainers specifically because they look too fit. They are afraid they will be asked to work too hard, beyond their comfort zone.”

“So why are they coming to the gym in the first place?” I asked. “What is motivating them if they don’t want to work out hard or change their bodies in the direction of athletic-looking trainers?”

“They’re just interested in staying the way they’ve always been. Maybe they’ve started putting on weight after they hit their 40’s and 50’s and just want to get back to where they were in their 30’s. They’re not interested in running marathons or lifting the heaviest weights in the gym. They don’t want to be pushed too hard, and they prefer trainers who look healthy but not extreme.”

Medically speaking, it doesn’t take extreme effort to be healthy. Many studies have shown that regular walking is adequate to stave off certain diseases, and weight loss success stories (chronicled at the National Weight Control Registry for example) usually result from adherence to a calorie-restricted diet and engagement in moderate exercise.

In a sense, these women who “don’t want to work that hard” are right – they don’t have to perform extreme feats to be healthy. However, I am still fascinated by the preference for “average looking” trainers and the apparent bias against athleticism. This must be a fairly common bias, though, because national gym chains (like Planet Fitness) have picked up on it and made it the cornerstone of their marketing strategy. “No judgments” – except if you’ve got buns of steel, I guess.

When I choose a trainer I am looking for someone who embodies the best of what exercise can offer. An athlete who has practiced their craft through years of sweat and effort… because that’s my North Star. Sure, I may never arrive at the North Star myself, but I like to reach. And that’s what motivates me.

But for others, having a professional athlete for a trainer may be a mindset misfit. If your aspiration is to be healthy but not athletic, then it makes sense to find inspiration in those who embody that attitude and lifestyle. The important thing is that we all meet the minimum exercise requirements for optimum health. According to the CDC, that means:

* 2 hours and 30 minutes (150 minutes) of moderate-intensity aerobic activity (i.e., brisk walking) every week

and

* muscle-strengthening activities on 2 or more days a week that work all major muscle groups (legs, hips, back, abdomen, chest, shoulders, and arms).

How you get there, and with whom you arrive, is up to you. Chubby or steely – when it comes to health and fitness the best mantra is, “whatever works!”

I recently found my way to an interesting NPR podcast via a link from Dr. Ranit Mishori (@ranitmd) on Twitter. The host of the show interviewed a physician (Dr. Mishori), an obesity researcher (Sara Bleich), and a family nurse practitioner (Eileen O’Grady) about how healthcare providers are trying (or not trying) to help patients manage their weight. Several patients and practitioners called in to participate.

I recently found my way to an interesting NPR podcast via a link from Dr. Ranit Mishori (@ranitmd) on Twitter. The host of the show interviewed a physician (Dr. Mishori), an obesity researcher (Sara Bleich), and a family nurse practitioner (Eileen O’Grady) about how healthcare providers are trying (or not trying) to help patients manage their weight. Several patients and practitioners called in to participate.

Health Leaders Media recently

Health Leaders Media recently Hospitals can be dangerous and inefficient; therefore it is easy to connect with Atul Gawande’s recent New Yorker essay “

Hospitals can be dangerous and inefficient; therefore it is easy to connect with Atul Gawande’s recent New Yorker essay “ New York Times blogger Tara Parker Pope

New York Times blogger Tara Parker Pope  I was taken aback by a recent conversation I had with a gym owner. She is interested in encouraging middle-aged women to come to the gym for beginner-level fitness classes and was planning a strategy meeting for her staff and key clients. I asked if I could join and she said that I was expressly un-invited. Slightly miffed I asked why that was so – after all, I’m a rehab physician who has devoted my career to getting people moving.

I was taken aback by a recent conversation I had with a gym owner. She is interested in encouraging middle-aged women to come to the gym for beginner-level fitness classes and was planning a strategy meeting for her staff and key clients. I asked if I could join and she said that I was expressly un-invited. Slightly miffed I asked why that was so – after all, I’m a rehab physician who has devoted my career to getting people moving.