July 23rd, 2011 by Dr. Val Jones in Health Tips, Opinion

No Comments »

Alright, I admit that the title of this post is a little dramatic. But it really does seem that most people I know socially have had a bad experience with the healthcare system lately. Take for example my friend whose 3- year-old went to the hospital for a common pediatric procedure – the little girl was overdosed on a medicine, aspirated, got pneumonia, went into respiratory distress (noticed first by her mom) and remained in the pediatric ICU for several days. The hospital staff swept the overdose under the rug, and outright denied it happened when faced with direct questioning. As outrageous as that all is, my friend chose not to pursue action against the hospital and staff for their error and behavior. She just “let it go” because no permanent harm had occurred.

Alright, I admit that the title of this post is a little dramatic. But it really does seem that most people I know socially have had a bad experience with the healthcare system lately. Take for example my friend whose 3- year-old went to the hospital for a common pediatric procedure – the little girl was overdosed on a medicine, aspirated, got pneumonia, went into respiratory distress (noticed first by her mom) and remained in the pediatric ICU for several days. The hospital staff swept the overdose under the rug, and outright denied it happened when faced with direct questioning. As outrageous as that all is, my friend chose not to pursue action against the hospital and staff for their error and behavior. She just “let it go” because no permanent harm had occurred.

Another dear friend was recently misdiagnosed with having a pulmonary condition when he was in heart failure from an arrhythmia… and almost had a stroke during a contraindicated pulmonary stress test. His simple conclusion: “doctors suck.” Was anyone held accountable for this? No. Again because no permanent harm had occurred.

Just the other night I was having dinner with some visitors from out of town. They both told me Read more »

March 9th, 2011 by LouiseHBatzPatientSafetyFoundation in Health Policy, True Stories

No Comments »

This is a guest post by Dr. Julia Hallisy.

Serious infections are becoming more prevalent and more virulent both in our hospitals and in our communities. The numbers are staggering: 1.7 million people will suffer from a hospital-acquired infections each year and almost 100,000 will die as a result.

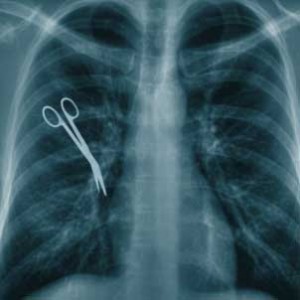

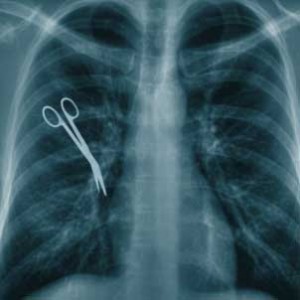

When our late daughter, Kate, was diagnosed with an aggressive eye cancer in 1989 at five months of age, our life became consumed by doctor visits, MRI scans, radiation treatments, chemotherapy — and fear. My husband and I assumed that our fight was against the ravages of cancer, but almost eight years later we faced another life-threatening challenge we never counted on — a hospital-acquired infection. In 1997, Kate was infected with methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in the operating room during a “routine” 30-minute biopsy procedure to confirm the reoccurrence of her cancer.

Kate’s hospital-acquired infection led to seven weeks in the pediatric intensive care unit on life support, the amputation of her right leg, kidney damage, and the loss of 70 percent of her lung capacity. While most infections are not this serious, the ones that are often lead to permanent loss of function and lifelong disabilities. In the years since Kate’s infection, resistant strains of the bacteria have emerged and now pose even more of a threat since they can be impossible to treat with our existing arsenal of antibiotics.

Patients afflicted with MRSA will often have to contend with the threat of recurrent infections for the rest of their lives. These patients live in constant fear of re-infection and often struggle with feelings of vulnerability and helplessness. Family members, friends, and co-workers may not fully understand the facts and have nowhere to turn for education about risks and prevention. Loved ones may worry unnecessarily for their own safety, which can cause them to distance themselves from someone who desperately needs their presence and support.

We have the knowledge and the ability to prevent a great number of these frightening infections, but the busy and fragmented system in which healthcare is delivered doesn’t encourage adequate infection control measures, and patients continue to be at risk. A significant part of the problem is that the public doesn’t receive timely and accurate information about the detection and prevention of MRSA and other dangerous organisms, and they aren’t engaged as “safety partners” in the quest to eliminate infections. Read more »

February 20th, 2011 by LouiseHBatzPatientSafetyFoundation in Opinion, True Stories

No Comments »

This is a guest post by J. Paul Curry, M.D.

I was inspired when I lost my best friend 15 years ago to a common medical-error phenomenon: The lack of monitoring patients in the hospital.

Losing Mark altered my entire career in medicine and started me on a long journey of trying to understand how this particular problem happens. The journey has been eye-opening for me for many reasons, and probably most importantly by striving to learn and understand how the human brain can deceive itself into believing that thoughtful, rational, goal-directed tactics are always the solution to finding the answers to highly-complex enigmas.

Actually, the blockbusting solutions that change the course of our culture — how we do things — are most often totally unpredictable and discovered by accident by disruptive innovators, such as Dr. Larry Lynn of the Sleep and Breathing Research Institute, willing to tinker on their own and against the grain of thousands of smart people who dismiss this kind of outlier work as fantasy. To get just how often this happens and why, I’d invite those unfamiliar with Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s work to read “The Black Swan : The Impact of the Highly Improbable” and other books of his. This is what we’re up against today.

Actually, the blockbusting solutions that change the course of our culture — how we do things — are most often totally unpredictable and discovered by accident by disruptive innovators, such as Dr. Larry Lynn of the Sleep and Breathing Research Institute, willing to tinker on their own and against the grain of thousands of smart people who dismiss this kind of outlier work as fantasy. To get just how often this happens and why, I’d invite those unfamiliar with Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s work to read “The Black Swan : The Impact of the Highly Improbable” and other books of his. This is what we’re up against today.

I was recently operated on, having a significant multi-level back surgery at one of the outstanding university spine programs in the country, supported by one of the elite anesthesia programs. I was told by the resident that I’d be going to the general care floor following my surgery, where I’d be checked on regularly. This was a given because I’m a fitness fanatic, but the resident wasn’t prepared for my followup questions. As I probed for more detail, it became apparent that no one in the organization had any inkling that nursing checks only occurring every four or eight hours on a patient fresh from surgery with patient-controlled narcotics was less than standard of care.

I told them I have mild sleep apnea and wanted pulse oximetry at minimum. I had to be upgraded to telemetry to get it. What’s more interesting is that there was so little understanding of this problem that they put me on pulse oximetry in a room where the only one who could watch it was me — the patient. Read more »

Alright, I admit that the title of this post is a little dramatic. But it really does seem that most people I know socially have had a bad experience with the healthcare system lately. Take for example my friend whose 3- year-old went to the hospital for a common pediatric procedure – the little girl was overdosed on a medicine, aspirated, got pneumonia, went into respiratory distress (noticed first by her mom) and remained in the pediatric ICU for several days. The hospital staff swept the overdose under the rug, and outright denied it happened when faced with direct questioning. As outrageous as that all is, my friend chose not to pursue action against the hospital and staff for their error and behavior. She just “let it go” because no permanent harm had occurred.

Alright, I admit that the title of this post is a little dramatic. But it really does seem that most people I know socially have had a bad experience with the healthcare system lately. Take for example my friend whose 3- year-old went to the hospital for a common pediatric procedure – the little girl was overdosed on a medicine, aspirated, got pneumonia, went into respiratory distress (noticed first by her mom) and remained in the pediatric ICU for several days. The hospital staff swept the overdose under the rug, and outright denied it happened when faced with direct questioning. As outrageous as that all is, my friend chose not to pursue action against the hospital and staff for their error and behavior. She just “let it go” because no permanent harm had occurred.