November 20th, 2012 by Dr. Val Jones in Announcements, Humor

Tags: Better Health, Does my butt look fast in these pants?, Dry Fit, Fitness, Funny Shirt, Get Better Health, Gift Idea, Humor, Nike, Running, Running Gear, Women's Running Shirt

1 Comment »

Does my butt look fast in these pants?

Since I started running (in earnest) a couple of years ago, I’ve been doing what I can to stay motivated. Running is a great sport because 1) it’s cheap 2) you can do it anywhere 3) it’s hard. So, because of #3 I welcome all opportunities to make running fun – and wearing amusing shirts during races seems like as good a strategy as any.

The idea for the “Does my butt look fast in these pants?” shirt came from a sign I saw at a recent marathon. A guy was cheering on the ladies with a homemade sign that read: “Your butt looks fast in those pants!” I laughed so hard it took me a quarter mile to recover. So I shamelessly stole his idea and made a Better Health women’s running shirt out of it. If you think it’s cool and want one too – I’d be happy to print you one. The larger the batch we order, the less expensive it will be.

So if you’re looking for a funny Christmas gift… or if you just want to thwart the race competition by making it impossible for them to pass you without sputtering out a laugh, let me know. Email me if you’d like to order a shirt and we’ll discuss details. My email is: val.jones@getbetterhealth.com (They are made of Nike dry-fit fabric, come in the colors shown only, and are available in Ladies S, M, L – if guys show interest I suppose we could order a run of men’s shirts too?). Let’s prepare to GET BETTER HEALTH this season… and run our way to victory in the battle of the bulge. 😆

November 9th, 2012 by Dr. Val Jones in Health Policy, Humor, Opinion

Tags: Assimilation, Concierge Medicine, DocTalker Family Medicine, Doug Farrago, Economies Of Scale, Health Insurance, Healthcare Costs, Hospitalists, Large Group Practice, Primary Care, Private Practice, Solo Practice, Star Trek, The Borg

4 Comments »

If you live in a small town or rural area of the United States, you may have noticed that family doctors are becoming an endangered species. Private and public health insurance reimbursement rates are so low that survival as a solo practitioner (without the economies of scale of a large group practice or hospital system) is next to impossible. Some primary care physicians are staying afloat by refusing to accept insurance – this allows them the freedom to practice medicine that is in the patient’s best interest, rather than tied to reimbursement requirements.

If you live in a small town or rural area of the United States, you may have noticed that family doctors are becoming an endangered species. Private and public health insurance reimbursement rates are so low that survival as a solo practitioner (without the economies of scale of a large group practice or hospital system) is next to impossible. Some primary care physicians are staying afloat by refusing to accept insurance – this allows them the freedom to practice medicine that is in the patient’s best interest, rather than tied to reimbursement requirements.

I joined such a practice a few years ago. We make house calls, answer our own phones, solve at least a third of our patients’ problems via phone (we don’t have to make our patients come into the office so that we can bill their insurer for the work we do), and have low overhead because we don’t need to hire a coding and billing team to get our invoices paid. Our patients love the convenience of same day office visits, electronic prescription refills, and us coming to their house or place of business as needed.

Using health insurance to pay for primary care is like buying car insurance for your windshield wipers. The bureaucracy involved raises costs to a ridiculously unreasonable level. I wish that more Americans would decide to pay cash for primary care and buy a high deductible health plan to cover catastrophic events. But until they do, economic pressures will force primary care physicians into hospital systems and large group practices. My friend and fellow blogger Dr. Doug Farrago likens this process to being “assimilated by the Borg.”

Doug offered a challenge to his readers – to customize the definition of Star Trek’s Borg species to today’s healthcare players. I gave it my best shot. Do you have a better version?

Who are the Borg:

The Borg are a collection of alien species that have turned into cybernetic organisms functioning as drones of the collective or the hive. A pseudo-race, dwelling in the Star Trek universe, the Borg take other species by force into the collective and connect them to “the hive mind”; the act is called assimilation and entails violence, abductions, and injections of cybernetic implants. The Borg’s ultimate goal is “achieving perfection”.

My attempt to customize the definition:

Hospitalists are a collection of primary care physicians that have turned into cybernetic organisms functioning as drones of the collective or hive. Hive collective administrators (HCAs), in association with partnered alien species drawn from the insurance industry and government, take other primary care physicians by economic force and connect them to “the hive mind”; the act is called assimilation and entails crippling reimbursement cuts, massive increases in documentation requirements, oppressive professional liability insurance rates, punitive bureaucratic legislation, and threat of imprisonment for failure to adhere to laws that HCA- partnered species interpret however they wish. The HCAs’ ultimate goal is “achieving perfect dependency” first for the drones, then for their patients, so that HCAs and their alien partners will become all powerful – dictating how neighboring species live, breathe, and conduct their affairs. Resistance is futile.

***

To learn more about my insurance-free medical practice, please click here. We can unplug you from the Borg ship!

August 13th, 2012 by Dr. Val Jones in Humor

Tags: cartoon, How To Choose Medical Specialty

1 Comment »

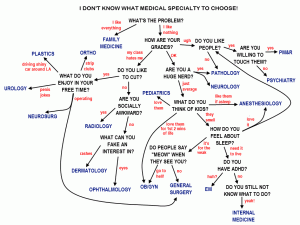

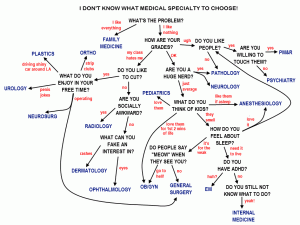

This is the best explanation I’ve ever seen. Please go to the cartoonist’s website for more.

August 7th, 2012 by Dr. Val Jones in Humor, True Stories

Tags: Abdominoplasty, Body Contouring, Muffin Top, Plastic Surgery, Scar Revision

No Comments »

"Muffin Top" Excision

At ten months of age I had a life-threatening condition that required risky abdominal surgery. The pediatric surgeon had to open my belly from end to end, right above my umbilicus. I lost most of my colon in the process, but the only apparent long term effect was an impressive seven-inch scar. After forty years of living, the scar had become “stuck,” resulting in a preponderance of skin slowly increasing its droop over the old gash. Basically, I had a non-clothing-induced “muffin top” and no amount of diet and exercise would improve it.

So off I went to the plastic surgeon, knowing that he couldn’t erase the scar but could improve the contours of my abdomen. In effect, I could retain my current appearance (that of a woman who had a permanent belly indentation caused by a lifelong history of wearing high-waisted pants that were two sizes too small) or I could opt for surgery and embody the look of an athlete who had picked a fight with Zorro. The choice was clear. I would settle for the long slice on a thin belly.

The problem with being a doctor under the knife is that you know exactly what the other guy is doing. This procedure was completed under local anesthesia, and so I was chattering away with my surgeon the entire time. Although it took us at least half an hour to numb the area, I could still feel every tug and pull, hear the click of forceps, and the crunch of clamps. It was a little unnerving to have one’s abdominal flesh wide open to the world – something I’d only expected of my patients previously. So my surgeon snapped a photo for my blog (see above) though I opted out of looking at the image in the middle of the procedure. I have my limits.

So why am I sharing this with you, dear readers? Well, I do have a few tidbits of advice for anyone who is planning to undergo a substantial cosmetic surgery under local anesthesia. I hope these are helpful:

1. Wear a comfortable pair of undies. The unisex/unisize disposable options available at the surgical suite do provide comic relief – if you think you’ll be needing that. The pair that I received were the color and texture of surgical booties and about the right size for a guy in the WWE.

2. Try not to kick the surgical assistant(s) during the numbing portion of the procedure (or during any other portion come to think of it). Let’s face it, lidocaine hurts. Each injection feels like a bee sting, and if you’ve got a lot of surface area to cover, you’re going to be spending the first half hour (or more) squeezing something with great vigor. Which leads me to my next tip:

3. Find something firm to grip during the procedure. I found the surgical table arms to be nicely padded and an adequate thickness for death grips. I did wonder if I should have brought one of those “stress balls” with me, or perhaps a pair of hand grip strengtheners from a local gym (see image to the left).

3. Find something firm to grip during the procedure. I found the surgical table arms to be nicely padded and an adequate thickness for death grips. I did wonder if I should have brought one of those “stress balls” with me, or perhaps a pair of hand grip strengtheners from a local gym (see image to the left).

4. Be prepared to make small talk with your surgeon for an hour or more. Preparing some “talking points” in advance could have made my patter more amusing, I suppose. But the art of distraction is a valuable asset in wide-awake surgeries. Your nervousness may actually make you a little extra charming, so don’t worry about what you say. Just do what it takes to keep your mind off the situation.

5. Don’t put your hands in the sterile surgical field. At certain times during the procedure your surgeon is likely to happen upon a spot that isn’t fully numb. You will probably respond with a squeal (or kick) and a loud “Ow!” The surgeon will then ask you what you are feeling and you must resist the urge to show him/her by pointing at it. Many an abdominal wound has been accidentally poked by well meaning patient fingers. Be careful! Just say you feel something sharp and the surgeon will know where it hurts… because he/she just did something to cause the reaction!

6. Get detailed post-op wound care instructions. You’ll probably exit the surgical suite with a lot of gauze and tape all over you, and it will occur to you later on that you haven’t the faintest idea when it’s safe to remove it. Can it get wet? Should you remove the steri strips? When do the stitches come out? When should you begin to use silicon scar gel? Do you need neosporin? Make sure you ask these questions before you’re released back into the wild.

7. Ask about movement restrictions and exercise precautions. You may be surprised by how restricted your movement should be in the first two weeks after surgery. I guessed that back flips would be counter-productive in my case, but didn’t realize that I couldn’t “walk fast” or twist at the waist. Make sure you understand what you can and can’t do to optimize your healing.

8. Take some pain medicine at least an hour before the local anesthetics are due to wear off. This was my biggest mistake. I asked if the wound would be painful later on and my surgeon denied any knowledge of potential post-op pain. So, six hours later when I felt as if someone had attacked my belly with a blow torch, I found some comfort in a maximum dose of ibuprofen and a vodka martini (and for those who know me well – yeah, I couldn’t finish the martini because it tasted gross).

9. Keep the scar protected and moist. Healing skin loves to be moist, especially early on. Ask your surgeon how best to accomplish that.

10. Get the stitches out on time. Don’t leave them in too long or you will be at risk for a larger or thicker scar. Disolvable stitches are convenient, but they do cause more inflammation which can lead to larger or more robust scar formation.

11. Tell your surgeon that you love the results (if they’re good!!) He/she will really appreciate the feedback.

I’m very pleased to report that my abdominal recontouring was a success, and I hope you’ll learn from my mistakes if you’ve got one coming up. Now I must strive to keep a new muffin top from growing by eating a healthy, calorie controlled diet (excluding real muffins!?) and exercising regularly. 😉

July 21st, 2012 by Dr. Val Jones in Health Tips, Humor, True Stories

Tags: Acute Care, Annoying Things About The Hospital, Bells, Caregivers, False Alarms, Flaws, Hospital Design, ICU, IV Drips, Noise, sleep deprivation

13 Comments »

An ICU Bed False Exit Alarm

I just spent the last 8 days in the hospital, at the bedside of a loved one. Although I squirmed the whole way through a tenuous ICU course and brief stop-over in a step-down unit, it was good for me to be reminded of what it feels like to be a patient – or at least the family member of one – in the hospital. The good news is that the staff were (by and large) excellent, and no major medical errors occurred. The bad news is that the experience was fairly horrific, mostly because of preventable design and process flaws. Having worked in a number of hospitals over the years, I recognized that these flaws were commonplace. So I’ve decided to tilt at this great hospital design “windmill” on my blog – with the hope that someone somewhere will make their hospital a friendlier place because of it.

Most of these design and process flaws have one thing in common: they prevent the patient from sleeping. In some circles, sleep deprivation is an organized form of torture reserved only for the most dangerous of terrorists. In other circles, it is hospital policy. And so, without further ado, here is my top 10 list of annoying hospital design flaws:

#1: False Alarms. Every piece of hospital equipment seems to be designed to beep for a complex list of reasons, many of which are either irrelevant or unhelpful. I snapped a photo of a particularly amusing (to me anyway) alarm (see above). This was a bed alert, signaling the “patient exit” of an intubated and sedated gentleman in the ICU. Not only was the location of the alert sign curious (if you could get close enough to the alert screen to read the text, you would surely already have noticed that the patient was AWOL) but it was triggered by mattress pressure changes that occurred when the patient was repositioned every 2 hours (as per ICU pressure ulcer prevention protocol).

The I.V. drip machines are probably one of the worst noise pollution offenders, beeping aggressively when an I.V. *might* need to be changed or when the patient coughs (this triggers the backflow pressure alarm, leading it to believe that a tube is blocked). Of course, I also thoroughly enjoyed the vitals monitor that beeped every time my loved one registered atrial fibrillation on the EKG strip – a rhythm he has been in and out of for years of his life.

#2: Intercom Systems. Apparently, some hospital intercom systems are wired into every patient room and permanently set at “full volume.” This way, every resting patient can enjoy the bleating cries for housekeeping, tray pickup, incoming nurse phone calls,physician pages, and transport requests for the entire floor full of individuals undergoing the sleep deprivation protocol.

#3: The Same Questions Ad Nauseum. Over-specialization is never more apparent than in the inpatient setting. There is a different team of doctors, nurses, PAs, and techs for every organ system – and sometimes one organ can have four teams of specialists. Take the heart for example – its electrical system has the cardiac electrophysiology team, the plumbing has the cardiothoracic surgery team, the cardiologists are the “minimally invasive” plumbers, and the intensivists take care of the heart in the ICU. Not only is a patient assigned all these individual micro-managing teams, but they work in groups – where they rotate vacations and on-call coverage with one another. This virtually insures that the sleep-deprived patient will be asked the same questions relentlessly by people who are seeing him for the very first time at 20 minute intervals throughout the day.

#4: Inopportune Intrusions. There are certain bodily functions that benefit from privacy. I was beginning to suspect that the plastic urinal was attached to the staff call bell after the fifth time that someone summarily entered my loved one’s room mid-stream. Enough said.

#5: Poorly Designed Tubing. Oxygen-carrying nasal cannulas seem to be designed to maintain a slight diagonal force on the face at all times. This results in the slow slide of the prongs from the nostrils towards the eye. Since the human eye is less efficient at absorbing oxygen than the lungs, one can guess what might happen to oxygen saturation levels to the average, sleep-deprived patient, and the resulting flurry of nursing disturbance that occurs at regular intervals throughout the night (and day). My loved one particularly enjoyed the flow of air pointed directly into his left eye as he attempted to rest.

#6: The Upside Down Call Bell. In an age of wireless technology, where almost every American has a cell phone and/or a flat screen television, it is odd that the light, TV, and nurse call bell control system must be tethered to a short cord positioned just outside of the patient’s reach. The controller is also designed so that the cord comes out of the box’s farthest point, causing it to remain upside down in the hands of anyone lucky enough to reach it from a chair or bed.

#7: Excessive Hospital Bands. In addition to multiple rotating IV access points, my loved one’s wrists and ankles were tagged with not one but four hospital band identifiers, including one neon yellow band sporting the ominous warning: “Fall risk.” If that little band is the only way that a staff member can ascertain a patient’s risk for falling down unassisted, then one is left to wonder about their powers of perception. In a moment of rare good humor, my loved one looked down at his assorted IV tubes and three plastic wrist bands and concluded, “I’m one stripe away from Admiral.”

#8: The Blank White Board. Sleep-deprivation-induced delirium can be rather disorienting. To help patients keep track of their core care team names, most hospital rooms have been outfitted with white boards. Ideally they are to be filled out each shift change so that the patient knows which activities are scheduled and the names of the staff that will be performing them. Filling out these boards is tiresome for staff members (not to mention that the dry erase markers are usually missing) and so they remain blank most of the time. This has an anxiety producing effect on patients, as the boards boldly proclaim that no nurse is taking care of them, and no activities are scheduled. I also noted that the size of the board lettering was a fraction smaller than a person with 20/20 vision could make out from the distance of the bed.

#9: The Slightly-Too-Tight Pulse Oximeter. Because being tethered to a bed with IV tubing, telemetry cords, and a nasal cannula is not quite irritating enough, hospital staff have devised a way to keep one unhappy finger in a constant, mild vice grip. This device monitors oxygenation status and helps to trigger alarms when nasal cannulas achieve their usual peri-ocular destination every 30 minutes or so.

#10: The Ticking And Creaking IV Drip. During the few rare moments of quiet, we did not enjoy any sort of blissful silence, but rather the incessant ticking of the I.V. drip machine. My loved one remarked that he felt as if he were trapped in an endless recording loop of the first 5 seconds of the TV show “Sixty Minutes.” And so if the alarms, tethering, interruptions, PA announcements, tubing, or white boards didn’t drive you mad, the auditory reinforcement of a ticking time bomb next to your head could bring you close to tears.

And so, because of all these nuisances (not to mention the ill-fitting hospital gowns, inedible food, and floors covered with various forms of “seepage” that penetrated patient socks on hallway ambulation attempts) we had one of the most unpleasant experiences in recent memory. All this, and no dissatisfaction with the surgical team or the primary procedure performed during the hospital stay. In the end, it’s the little things that can drive you crazy – or make you well.

If you live in a small town or rural area of the United States, you may have noticed that family doctors are becoming an endangered species. Private and public health insurance reimbursement rates are so low that survival as a solo practitioner (without the economies of scale of a large group practice or hospital system) is next to impossible. Some primary care physicians are staying afloat by refusing to accept insurance – this allows them the freedom to practice medicine that is in the patient’s best interest, rather than tied to reimbursement requirements.

If you live in a small town or rural area of the United States, you may have noticed that family doctors are becoming an endangered species. Private and public health insurance reimbursement rates are so low that survival as a solo practitioner (without the economies of scale of a large group practice or hospital system) is next to impossible. Some primary care physicians are staying afloat by refusing to accept insurance – this allows them the freedom to practice medicine that is in the patient’s best interest, rather than tied to reimbursement requirements.

3. Find something firm to grip during the procedure. I found the surgical table arms to be nicely padded and an adequate thickness for death grips. I did wonder if I should have brought one of those “stress balls” with me, or perhaps a pair of hand grip strengtheners from a local gym (see image to the left).

3. Find something firm to grip during the procedure. I found the surgical table arms to be nicely padded and an adequate thickness for death grips. I did wonder if I should have brought one of those “stress balls” with me, or perhaps a pair of hand grip strengtheners from a local gym (see image to the left).